These Doctors Mean Business

While patient care is an important part of the careers of the majority of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine graduates, some find that they can make the greatest leadership contributions in non-clinical roles.

“The solid foundation that these graduates have received in the art and science of medicine allows them to function much more effectively and creatively as they take on positions of great responsibility in a variety of fields, some health-related and some not,” said Bonnie Miller, M.D., associate vice chancellor for Health Affairs and senior associate dean for Health Sciences Education.

Fewer than 10 percent of physicians nationwide choose non-medical careers. But according to a recent study published in Academic Medicine, the number of medical schools offering joint MD-MBA training has increased fivefold in the last two decades. John Prescott, M.D., chief academic officer of the Association of American Medical Colleges, says both physicians and the companies that employ them stand to benefit from the skills acquired in medical school.

“Individuals are looking for all sorts of opportunities to contribute to society. For some it may be in a clinical realm, for others it might be in research and for others it might be education or a combination of all of those. There has always been a group that has looked for additional opportunities to meld the training they got in medicine with other experiences and bring that medical education, training and thought process to new endeavors.”

“Don’t you miss being a physician?” is a common question posed to doctors who have chosen to care for clients rather than patients.

“My answer has always been that I am still a physician, I am always going to be a physician. I take what I learned in medical school and in the care of patients forward into whatever endeavor I am going into. I think it’s a way that medicine can impact society in a different way,” Prescott said.

* * *

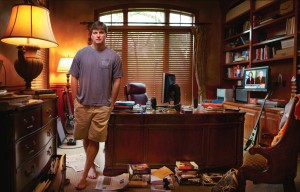

Michael Burry, M.D.,’97, was sitting in first class during a transcontinental flight when a flight attendant asked if there was a doctor on board who could help with a medical emergency.

Burry got up from his seat, and as he walked the length of the plane to reach the passenger, his prevailing thought was that he sincerely hoped someone else would get there first.

“Thank God there was someone else there already,” he said with a chuckle.

While Burry still keeps his medical license and continuing medical education credits current, he is more comfortable managing money than patients.

Burry began looking at stock in the second grade and investing in high school. While he had an obvious gift for running money, he also had an altruistic side and a desire to help others. He decided to attend medical school and wanted to do so outside of his home state of California. After visiting several schools, he settled on Vanderbilt.

“What struck me about Vanderbilt was how nice everyone was, and it seemed to have a generous, giving, very polite and welcoming culture. I ended up deciding I would rather go to Vanderbilt and get the medical degree and the best education in the best environment that I possibly could before deciding fully what path I would take.”

In medical school Burry began to establish himself as an investment whiz kid. What started as a hobby became a viable career option when he was a neurology resident at Stanford, which coincided with the advent of the Internet age. He was caring for patients during the day and blogging about investment until 3 a.m.

“In the mid ‘90s the Internet was a wide open space, and there were a lot of needs that were not yet met. There were holes in the investing knowledge base on the Web and they were pretty obvious. So I attempted to fill it in a very small way,” he explained.

It was during his third year of residency, about the time that he needed to look for a job, that he had to choose between medicine and finance.

“At that point I figured rather than going through my final year of residency it seemed like I needed to make a choice. Am I going to continue in medicine or am I going to make the break? I decided to make the break.”

In 2000 Burry announced on his investment website that he was leaving medicine and going into the hedge fund business. He founded Scion Capital, and in just a few weeks Gotham Capital and White Mountain Insurance invested in his management company, what Burry calls a turning point.

The company was successful early on and enjoyed several good years, albeit with a slight downturn in 2006. But, its biggest year was 2007, and in the financial world, it was legendary.

“What I saw in the housing market was a large macro event that was going to happen, and I figured out a way to time when it would happen. I was looking for the point where housing prices were maximally inflated by certain types of mortgages that were coming into existence that hadn’t existed before,” Burry explained.

“I watched for those types of mortgages to penetrate the subprime market, and there came a point where I decided in 2005 this wouldn’t go on more than another couple years because mortgages had come out that didn’t require much of a down payment or much of a payment during the teaser period that lasted between two and three years.

“When we got to the point where they were being offered to people who obviously could not make the payments outside the teaser period, I knew that in two to three years the mortgage market would collapse because prices would no longer go up. All of these mortgages were based on the idea that prices would go up and people would refinance out before they had to exit the teaser period.”

This conclusion led Burry to short the market by persuading Goldman Sachs to sell him credit default swaps against subprime deals he saw as vulnerable. In 2007 the housing market collapsed, and Burry’s hedge fund ultimately recorded returns of 489.34 percent. He was able to give $750 million back to investors.

In 2008, he closed down the company and for several years focused only on his personal investments and his family. He lives in California with his wife and two sons, Nicholas, 13, and Michael, 11. In September 2013, he started another hedge fund—Scion Asset Management.

He has been back to Vanderbilt in recent years, generously funding the Burry Chair in Cognitive Childhood Development, which is held by Beth Malow, M.D., professor of Neurology. He said he feels that his years as a medical student helped shape who he is now.

“As you go through the medical school curriculum, there is a lot of pressure, a lot of hard work, a lot of information, and I think that really helped me refine my own self-knowledge and awareness and helped me figure out who I really was.

“I would say that I was an average medical student, and I saw others who were clearly born to be doctors. It seemed just as clear that I was not born to be a doctor. It didn’t have anything to do with the people at Vanderbilt or the patients I was exposed to. It really had more to do with the students I was exposed to. My fellow students were a terrific foil against which I could recognize where I ultimately stood.

“At this point I can’t regret anything I’ve done in life. I am very glad I went down that path and received a medical education and that I continued into residency. I think it’s been a terrific knowledge base throughout my life.”

Watch video of Michael Burry’s 2011 Chancellor’s Lecture »

* * *

When Joann Data, M.D., Ph.D.,’77, approached her father, a chemist and a faculty member at Purdue University, during high school, and informed him she wanted to major in chemistry in college, he told her, ‘You don’t want to have women chemists in the laboratory; they will cause nothing but accidents and explosions.’

“He supported my education but did not support things that were in his space,” Data said.

With a strong desire to study pharmacology, she decided to apply to medical school. Her father’s response: ‘You’ll never get into medical school.’

“It couldn’t hurt to try,” Data told him. She was accepted to Washington University School of Medicine, among others.

“I think I actually floated to my dad’s office to tell him I was accepted,” she said. “What I learned later was that he could get me to do what he wanted me to do by telling me I couldn’t. I would do anything to prove him wrong because he thought he was always right.”

That determination has served Data well over the last 37 years as she climbed to the top of the corporate pharmaceutical ladder and then moved into the consultant world.

From the time she was a child, she was interested in how drugs work and why some people react well to certain drugs while others do not.

“My mentor during med school told me the most important thing I could do if I really wanted to help patients and understand how drugs worked in them was to get training in either internal medicine, pediatrics or anesthesiology … so I took the path that interested me most and did my house officer training in internal medicine, knowing full well that I was going to ultimately go into clinical pharmacology,” she said.

Upon receiving her medical degree in 1970, she wrote letters to the six or seven clinical pharmacology programs in the country at the time, hoping to land in one that would allow her to pursue both a fellowship and her Ph.D., simultaneously.

“One of the things my dad said was there is an advantage to having an M.D./Ph.D., because when you are a physician you think about one person at a time. When you’re a Ph.D., you think of populations of people. The mix of those two helps you be a better thinker.”

She received the most positive response from John Oates, M.D., the Thomas F. Frist Sr. Professor of Medicine and the founding director of Vanderbilt’s Division of Clinical Pharmacology. He was receptive to her plan, and she received her Ph.D. in Pharmacology in 1977 simultaneously completing her fellowship in Clinical Pharmacology and then serving as an instructor in Medicine and Pharmacology until her graduation.

“It was a great experience,” she said of her time at Vanderbilt.

Data was ready to pursue her love of clinical pharmacology, but had to decide whether to do that in the academic arena or industry.

“I talked to Dr. Oates again and told him it would be most logical for me personally to go into the industry. I was so scared to talk to him because I knew that wasn’t what was expected of me, especially then. He said, ‘Let me give you some advice: before you accept the job get everything you want and then some. Get your position somewhere between medicine and basic science. Never stop being in touch with the academic world.’ That’s what I did.”

Data joined The Upjohn Company doing cardiovascular clinical investigation. She held positions at Burroughs-Wellcome Co., and Hoffmann-La Roche prior to returning to The Upjohn Company where she became corporate vice president for Worldwide Pharmaceutical Regulatory Affairs and Project Management. When Upjohn merged with Pharmacia, Data joined CoCensys, Inc. as senior vice president of Clinical Development and Regulatory Affairs.

From there she became the senior vice president of Regulatory Affairs and Quality Assurance at Amylin Pharmaceuticals Inc.

“I worked for a number of different biotech companies because most of them don’t last very long. I ended up at Amylin and was able to get two drugs on the market for this little tiny company in the course of six months. It took a long time to get them ready to submit, but once we got them submitted we got them approved quickly.”

Over the course of her remarkable career, Data helped get 38 new drugs on the market, including two diabetes drugs (Symlin and Byetta), DepoProvera and Rogaine for women.

“I was really thrilled with each of these approvals because I was very much involved in the approval process. Standing before the FDA convincing the Dermatology Advisory Committee that women do have male pattern baldness was good experience. Clinical trials had shown that Rogaine really did change people’s lives.”

Today she is a consultant for the pharmaceutical industry and bioventure groups evaluating programs to see if their products are likely to make it to market and making recommendations regarding financial backing.

Data serves on an advisory board working with Nancy Brown, M.D., chair of the Department of Medicine, and former chief of the Division of Clinical Pharmacology. Data stops by Brown’s office when she’s in Nashville to catch up. Her storied career has taken her around the world, but she’s always happy to touch down in Tennessee, where she and her husband, Herman Cantrell, own homes in Sparta and Franklin.

She said it doesn’t bother her when people ask her why she doesn’t practice medicine.

“I don’t practice it per se but I practice medicine on a population of people. In practicing it that way you might not know patients personally, but you look at the case reports and the information collected and you say, ‘there is a trend here, a problem, and there’s got to be some commonality to it.’ It makes you put groups together to understand why some people react differently than others to the same medication.

“It doesn’t bother me at all that I don’t have a clinical practice because I did make the right decisions for the right reasons, listened to the sage advice of colleagues, and it’s been and continues to be a wonderful career.”

* * *

When Edd Fleming, M.D.,’89, was a fourth-year medical student, VUSM Dean John Chapman presented him the Jester Award at Cadaver Ball, a humorous award to highlight some quirk of a member of the senior class.

Fleming received it because he was deemed as likely to go to law school as to finish a residency.

“I certainly had a lot of varied interests. I was interested in the economics of health care and how it was delivered and was interested in the science, so all those things were bouncing around,” he said.

He finished his residency and never did go to law school, but shortly after completing a fellowship in pulmonary medicine and critical care medicine at the University of California-San Francisco, he had a decisive moment while waiting to hear if he would receive an NIH grant he had applied for.

“I was aware that the grant was the thing that was either going to fund me going forward or not, so it was obviously important. In that intervening time I decided that I didn’t want to spend 80 percent of my time in the lab, which was a requirement of the grant. That sort of galvanized me into action because I’d been thinking a lot about what else I wanted to do. Did I want to go into industry? Work at a startup?”

He had a fortuitous conversation at a dinner party with someone who worked at McKinsey & Company, a global management consulting firm. This person described a project he was working on—an expansive study on global health care productivity, which sounded fascinating to Fleming.

“I blissfully applied and was lucky enough to get an offer and truthfully didn’t fully understand what McKinsey did,” he said. “I slipped into it not thinking I was going to stay very long and here I am 17 years later.”

Fleming is one of several physicians in McKinsey’s West Coast Office, which has 450 consultants across four locations—San Francisco, Silicon Valley, Seattle and Southern California. He focuses on supporting clients across the health care sector and leads McKinsey’s R&D practice within the pharmaceuticals and medical products industries.

He said he draws on both the technical knowledge and what he calls the softer skills that he gained from medical school and residency.

“I spend a lot of time with R&D organizations… how they design clinical trials and deciding what the end points should be and how they move trials through execution efficiently. That pulls constantly on my medical knowledge and forces me to stay up to date and learn and stay ahead of the game,” he said.

His ability to interview clients and extract information from them can be traced to his days of taking a patient’s medical history.

“Just learning to conduct a basic patient interview that ranges from those who will tell you everything to really having to work it out of someone to find out what the problem is—those instincts and how you open people up is incredibly valuable to me in my job today.”

* * *

Enoch Sizto, M.D.,MBA, ’14, pursued his medical degree and master’s in business administration simultaneously at Vanderbilt and graduated in August 2014. Fresh out of medical school, with two degrees in hand, he had a decision to make.

He had invested a lot of time—and money—in medical school, beginning as a pre-med student at the University of California—San Diego. After he graduated from there, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy working as a combat medic with 1st Marine Division, deploying to the front lines in Iraq.

“At the time I was not sure if I would make the military a career or if I would jump back out and study medicine,” said Sizto, 32, who was on active duty for four-and-a-half years.

He ultimately decided to enroll in medical school, and at the suggestion of a college friend whose father works at Vanderbilt, he checked the box on his AMCAS application to have it sent here.

“When I visited Vanderbilt, I was drawn to the friendly atmosphere and collegiality and Vandy became my top choice,” he said.

Vanderbilt’s dual MD/MBA program consists of three full years in medical school, followed by one year in the Owen Graduate School of Management, concluding with a semester in each. One month into the MBA program, he was bitten by the entrepreneurial bug when he began working with a start-up medical device company—Vitalnx—and eventually served as CEO for a year.

“After working with Vitalnx, I realized that this is what I need to do. Since then, this has been my trajectory. I plan to pursue entrepreneurship instead of pursuing a residency.”

Sizto is going to work for Remedify, a health information technology startup company based in Nashville. As one of the three co-founders of Remedify, he will manage the company’s strategy and operations.

The company provides software solutions for medical device sterilization, taking complex, detailed instructions found in documentation and displaying them in a uniform, easy-to-read, icon-driven format.

“This is critical to ensuring that instruments are properly cleaned and sterilized between patient cases to prevent potentially harmful or deadly complications. By making important information easily accessible and streamlining this process, Remedify takes the guesswork out of sterilization, making operating rooms safer for patients,” he explained.

Remedify also offers compliance solutions for health care facilities, providing a Web-based, searchable device documentation database.

“The military and med school are both challenging environments; you learn a lot about yourself. They offered a chance to hone perseverance and creative problem-solving skills, which helped in business school as well. Seeing how different clinics and hospitals work was definitely beneficial during the MBA portion of my studies and will serve me well as I pursue my business career in the health care industry,” Sizto said.

“I’ve been able to combine the clinical experiences from medical school, problem-solving skills from working in a combat zone, and business knowledge from Owen and use them to help solve problems in our health care system.”