By Leigh Ann Gardner (MSTP Sr. Grants Manager)

November 3: British surgeon Wilfred Trotter, born on November 3, 1872, in Gloucestershire, England, is remembered for his psychological theories on herd mentality as well as his surgical skills. He received degrees from London’s University College Hospital and initially entered medicine as a surgeon. He started as a general surgeon, as surgical specialization was in its early days, but he did become known for his expertise in the surgical treatment of neck and head tumors and was an early pioneer in using thyroidectomy for Graves’ disease. By 1920, he was regarded as an expert surgical oncologist. He was also interested in sociology and psychology, particularly the psychology of crowds. In 1908 and 1909, he published a paper on the herd instinct of humans, which was considered groundbreaking in understanding group behavior. In 1916, he published a book on the subject, Instincts of the Herd in Peace and War. Trotter died in 1939, and you can read more about his life here. You can access his 1916 work, Instincts of the Herd in Peace and War here.

November 3: British surgeon Wilfred Trotter, born on November 3, 1872, in Gloucestershire, England, is remembered for his psychological theories on herd mentality as well as his surgical skills. He received degrees from London’s University College Hospital and initially entered medicine as a surgeon. He started as a general surgeon, as surgical specialization was in its early days, but he did become known for his expertise in the surgical treatment of neck and head tumors and was an early pioneer in using thyroidectomy for Graves’ disease. By 1920, he was regarded as an expert surgical oncologist. He was also interested in sociology and psychology, particularly the psychology of crowds. In 1908 and 1909, he published a paper on the herd instinct of humans, which was considered groundbreaking in understanding group behavior. In 1916, he published a book on the subject, Instincts of the Herd in Peace and War. Trotter died in 1939, and you can read more about his life here. You can access his 1916 work, Instincts of the Herd in Peace and War here.

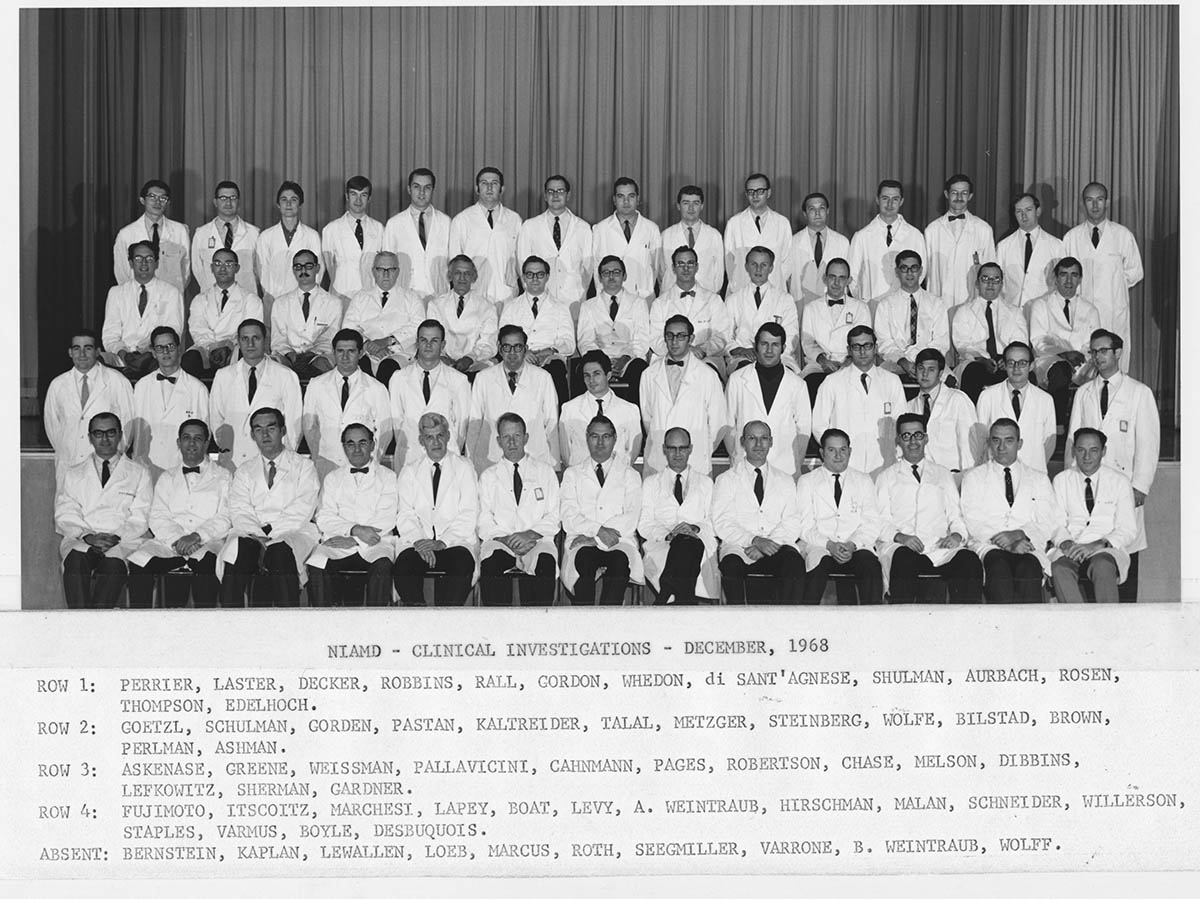

November 11: In recognition of Veteran’s Day on November 11, we are highlighting the “Yellow Berets,” a group of NIH physician scientists who served in the Public Health Service to fulfill their service obligations during the Vietnam War. Formally known as the Associate Training Program, which was under the command of the Commissioned Corps of the United States Public Health Service, applicants performed both clinical duties at NIH as well as bench research in the lab of a senior scientist. Although their actual title was Clinical Associate, they became known as Yellow Berets, due to a perception that the participants were using a cowardly way to avoid active-duty military service in the Vietnam War. In time, this program trained the best-known of that generation of physician-scientists, including 6 Nobel laureates: J. Michael Bishop (1989), Alfred Gilman (1994), Stanley Prusiner (1997), Ferid Murad (1998), Richard Axel (2004), and Harvey Alter (2020). Another well-known participant in this program was Anthony Fauci. In time, the term “Yellow Beret” became a badge of honor for those that participated, and those participants had a large impact on the academic institutions to which they returned. In 1998, a survey showed that a quarter of the faculty of Harvard Medical School were alumni of this program. You can learn more about the Yellow Berets here and here.

November 11: In recognition of Veteran’s Day on November 11, we are highlighting the “Yellow Berets,” a group of NIH physician scientists who served in the Public Health Service to fulfill their service obligations during the Vietnam War. Formally known as the Associate Training Program, which was under the command of the Commissioned Corps of the United States Public Health Service, applicants performed both clinical duties at NIH as well as bench research in the lab of a senior scientist. Although their actual title was Clinical Associate, they became known as Yellow Berets, due to a perception that the participants were using a cowardly way to avoid active-duty military service in the Vietnam War. In time, this program trained the best-known of that generation of physician-scientists, including 6 Nobel laureates: J. Michael Bishop (1989), Alfred Gilman (1994), Stanley Prusiner (1997), Ferid Murad (1998), Richard Axel (2004), and Harvey Alter (2020). Another well-known participant in this program was Anthony Fauci. In time, the term “Yellow Beret” became a badge of honor for those that participated, and those participants had a large impact on the academic institutions to which they returned. In 1998, a survey showed that a quarter of the faculty of Harvard Medical School were alumni of this program. You can learn more about the Yellow Berets here and here.

November 17: Physician and bacteriologist Hans Zinsser, known for his work on typhus, was born on November 17, 1878, in New York City to German immigrants. He received his undergraduate and master’s degrees, as well as his medical degree, from Columbia University. After an initial position at Stanford University, Zinsser returned to Columbia University as a professor and head of the bacteriology department in 1913. During World War I, he joined the Red Cross Typhus Commission in Serbia, where he worked in a typhus hospital. In 1923, he traveled to Russia with the League of National to study a typhus outbreak, and he also left Columbia to lead the Bacteriology and Immunology Department at Harvard Medical School. He continued researching typhus and eventually isolated the bacterium that caused a European variant of the disease. He developed the first anti-typhus vaccine. He also wrote a number of books, but was best known for his work, Rats, Lice, and History (1935), which was a sort of “biography” of typhus, and described the outsized impact that disease has on the course of human history. Zinsser also served as the sixth president of the American Association of Immunology and died in 1940 of lymphatic leukemia. You can read more about his life here and here. You can find a copy of Rats, Lice, and History here.

November 17: Physician and bacteriologist Hans Zinsser, known for his work on typhus, was born on November 17, 1878, in New York City to German immigrants. He received his undergraduate and master’s degrees, as well as his medical degree, from Columbia University. After an initial position at Stanford University, Zinsser returned to Columbia University as a professor and head of the bacteriology department in 1913. During World War I, he joined the Red Cross Typhus Commission in Serbia, where he worked in a typhus hospital. In 1923, he traveled to Russia with the League of National to study a typhus outbreak, and he also left Columbia to lead the Bacteriology and Immunology Department at Harvard Medical School. He continued researching typhus and eventually isolated the bacterium that caused a European variant of the disease. He developed the first anti-typhus vaccine. He also wrote a number of books, but was best known for his work, Rats, Lice, and History (1935), which was a sort of “biography” of typhus, and described the outsized impact that disease has on the course of human history. Zinsser also served as the sixth president of the American Association of Immunology and died in 1940 of lymphatic leukemia. You can read more about his life here and here. You can find a copy of Rats, Lice, and History here.

November 29: Food chemist María Ylagan Orosa, known for both her food innovations in her native country as well as her work in the resistance against Japanese occupation during World War II, was born on November 29, 1893, in Taal, Batangas, in the Philippines. In 1916, she came to the United States, where she studied at the University of Washington in Seattle, where she earned undergraduate and master’s degrees in chemical and pharmaceutical science. While at university, she worked in food labs, where she tested food to ensure they met government standards, and she worked summers in Alaska in fish canneries, where she learned about industrial-scale canning and food preservation. She returned to the Philippines in 1922, where she obtained a government job with the Philippine Bureau of Science; by 1934, she was head of a division in the government’s Bureau of Plant Industry. She spent her career learning how to use and preserve local foods, hoping to free Filipinos from foreign control by teaching them how to use and preserve local foods. She taught Filipinos about home canning, and was responsible for over 700 innovations and recipes, including a drink called Soyalac (made from soya beans), darak (rice flour high in vitamin B-1), and the development of banana ketchup. Tomato ketchup was popular in the Philippines but expensive, as tomatoes could not be grown there; she developed banana ketchup to serve as a less expensive substitute. She remained in Manilla during the Japanese occupation of her country in World War II, and she and her team developed nutrient-dense rations for those trapped in Manilla. It is also believed that she smuggled food to those interred in prisoner of war camps in the Philippines. She was killed during the American attack on the Japanese on February 13. 1945. She is honored in her country with statues, and a street is named in her honor in Manilla. You can learn more about her life here and here.

November 29: Food chemist María Ylagan Orosa, known for both her food innovations in her native country as well as her work in the resistance against Japanese occupation during World War II, was born on November 29, 1893, in Taal, Batangas, in the Philippines. In 1916, she came to the United States, where she studied at the University of Washington in Seattle, where she earned undergraduate and master’s degrees in chemical and pharmaceutical science. While at university, she worked in food labs, where she tested food to ensure they met government standards, and she worked summers in Alaska in fish canneries, where she learned about industrial-scale canning and food preservation. She returned to the Philippines in 1922, where she obtained a government job with the Philippine Bureau of Science; by 1934, she was head of a division in the government’s Bureau of Plant Industry. She spent her career learning how to use and preserve local foods, hoping to free Filipinos from foreign control by teaching them how to use and preserve local foods. She taught Filipinos about home canning, and was responsible for over 700 innovations and recipes, including a drink called Soyalac (made from soya beans), darak (rice flour high in vitamin B-1), and the development of banana ketchup. Tomato ketchup was popular in the Philippines but expensive, as tomatoes could not be grown there; she developed banana ketchup to serve as a less expensive substitute. She remained in Manilla during the Japanese occupation of her country in World War II, and she and her team developed nutrient-dense rations for those trapped in Manilla. It is also believed that she smuggled food to those interred in prisoner of war camps in the Philippines. She was killed during the American attack on the Japanese on February 13. 1945. She is honored in her country with statues, and a street is named in her honor in Manilla. You can learn more about her life here and here.