Research fellow and MPH candidate Saad combines passions for sustainability and plastic surgery to reconstruct approaches to medical waste.

By: David Cohen

Since collaborating with Climate Vault in 2021, an award-winning non-profit organization focused on reducing emissions, Vanderbilt University has achieved carbon neutrality decades ahead of its original goal. The university continues to seek opportunities to further enhance sustainability by investing in renewable energy and green spaces across campus. Despite economic incentives posing challenges for individuals globally to support new sustainable methods, Vanderbilt’s efforts have ignited local interest in new initiatives aimed at reducing the university’s carbon footprint.

According to Mariam Saad, M.D., M.P.H.’24, environmental sustainability has always been a niche interest of hers. From recycling to composting, she constantly explores new ways to practice environmental sustainability. Her passion was nurtured in part by watching David Attenborough’s documentaries during her childhood, which heightened her awareness of environmental issues. When her home country began to suffer from environmental crises, she stepped in without hesitation to make a difference.

“I wear dual hats at Vanderbilt; I have two roles here as an MPH student on the health policy track and as a research fellow with the department of plastic surgery, where I’m aiming to pursue residency in reconstructive surgery. While I ultimately hope to become a practicing surgeon, I also aim to create an impact in the sustainability field by implementing new interventions that address hospital waste issues.”

–Mariam Saad, MD, MPH’24

“I grew up in Beirut, Lebanon in the Middle East. While it is a very vibrant and diverse country, Lebanon unfortunately lacks a lot of organization and infrastructure in the basics of human life, especially waste and garbage,” said Saad.

In 2015, a major landfill site in Lebanon shut down and government authorities failed to develop appropriate measures to manage the growing waste problem. Dumping garbage onto public streets became routine, plunging Lebanon into a pit of public health crises and political chaos.

“I remember seeing mountains of garbage in my neighborhood. This sight could have been significantly reduced if people actually implemented waste reduction methods such as recycling. So, my passion for sustainability grew from my efforts to save my community.”

Saad vividly recalls reaching out to local NGOs and distributing flyers around nearby apartments to garner as much support as possible. She watched in horror as the surplus of waste led to disease outbreaks.

“I did my best to encourage everyone around me to recycle and financially support NGOs so they could help take some of the garbage away. At the time, if I hadn’t been the one printing out flyers, going to different buildings, taping them to entrance doors and elevators, and talking to all the building staff I could find to disseminate public notices, my living conditions might have become unbearable. I didn’t solve the crisis alone, but the experience of aiding my neighborhood was truly empowering. I carried this experience with me when I came to the U.S.,” said Saad.

Though a rising second year MPH student, Saad has only been in America for two years. When she noticed opportunities for improvements in Nashville’s recycling processes, she saw opportunities to merge her passion for environmental sustainability with her academic work.

“I wear dual hats at Vanderbilt; I have two roles here as an MPH student on the health policy track and as a research fellow with the department of plastic surgery, where I’m aiming to pursue residency in reconstructive surgery. While I ultimately hope to become a practicing surgeon, I also aim to create an impact in the sustainability field by implementing new interventions that address hospital waste issues. My mentors, Dr. Brian Drolet, Program Director, and Dr. Galen Perdikis, Chair for the Department of Plastic Surgery at VUMC, have been highly supportive in helping me explore these interests. We’ve had numerous discussions about improving recycling practices in Nashville, and they played a pivotal role in helping me find ways to intersect my interest in plastic surgery with recycling initiatives.”

Within the MPH Program, students are tasked to integrate perspectives from other sectors and/or professions to promote and advance population health. Many students collaborate with various health professionals to pursue interprofessional education (IPE) projects which allows them to collaborate with partners to address real-world community-defined needs. For Saad, the IPE project was the perfect opportunity to continue making community impacts through recycling.

“I wanted to direct my project from a medical perspective, because the U.S. healthcare sector generates approximately 6 million tons of waste annually, with operating rooms in hospitals contributing to about 70% of it. Pollution from waste is a significant global health problem. From discovering new sources of renewable energy to exploring ways to reduce carbon emissions, the possibilities to address pollution are limitless. I believe this project could serve as a starting point to address some of Nashville’s environmental needs, particularly after learning about the city’s landfill shortage,” said Saad.

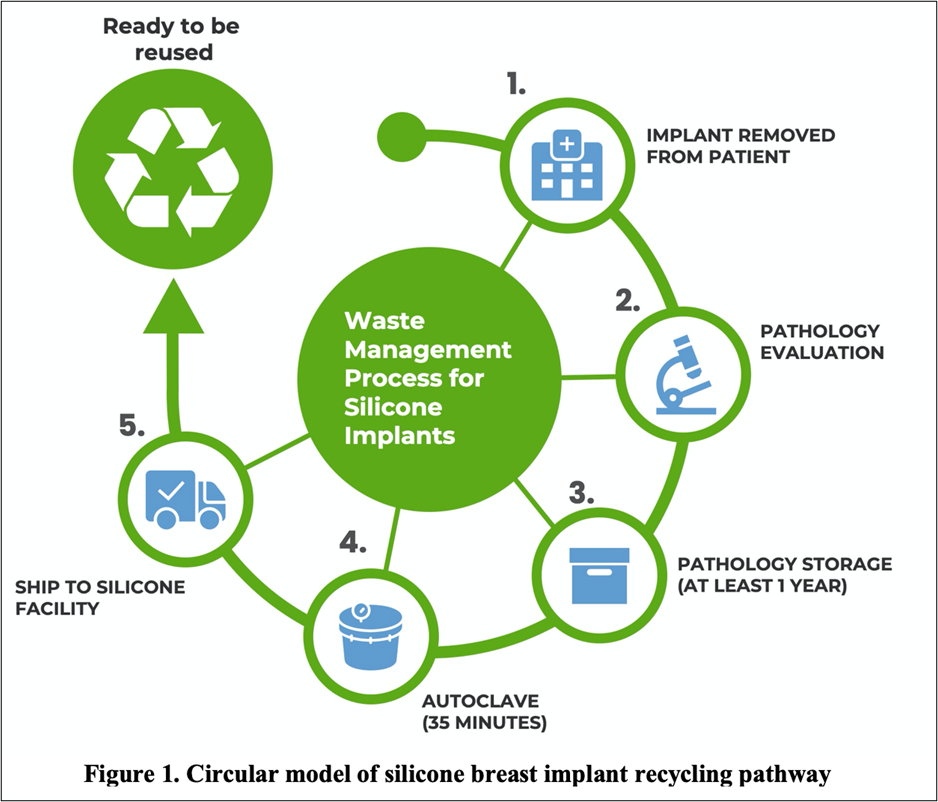

For her IPE project, Saad has focused on recycling silicone used in medical environments, one of the major materials used in plastic surgery procedures. Typically, the pathology department at VUMC temporarily stores silicone implants removed on-site until the local municipality collects medical waste from the hospitals and disposes of them in landfills. However, given Nashville’s escalating landfill shortage and the associated pollution, Saad has navigated her efforts towards finding renewable methods to reuse silicone.

“Silicone is an extremely flexible and durable material that can be recycled to produce various products. Unlike plastic recycling, which involves grinding of particles, silicone recycling employs a chemical model involving the depolymerization of silicone into monomers and cyclins. These components are then re-polymerized to form industrial grade silicone oil. From there, this recycled silicone can be used in sealants, lubricants, paint and even kitchen utensils, among other things. In medicine, silicone is used for prosthetics in breasts, chins, and occasionally ears. Sometimes, implants are removed due to infection or replaced with newer ones for safety purposes. Instead of disposing of or incinerating all the silicone removed from patients, I reached out to a silicone recycling company to develop a system to reuse these implants.”

Saad has already obtained clearance from the offices of environmental safety and risk management at VUMC to pursue this initiative, and has begun coordinating measures with the pathology department to retrieve waste. She has also received authorization to collaborate with VUMC’s sterilization department to ensure proper cleaning of the silicone, as well as organized arrangements for the implants to be transported to UPS and shipped to a recycling company for distribution.

“My primary mode of communication was always a phone call to investigate whether the parties involved could actually help. Then all downstream communication happened via email. Getting individuals to align with my vision and understand how my model would directly impact public health was a challenge, but I was pleasantly surprised by the amount of support I received from everyone I reached out to. The entire recycling process requires meticulous oversight and is truly a team effort,” said Saad.

While she awaits further data consolidation from the success of her recycling model thus far, Saad estimates that employing the silicone recycling pathway will result in an 80% decrease in CO2 emissions compared to traditional methods. She intends to analyze the carbon emissions in more detail based on the amount of silicone produced per ounce versus recycled, and will adapt her model accordingly to prioritize the most environmentally friendly initiatives.

“My team and I received a generous climate initiative grant from the radiology department to reduce VUMC’s carbon footprint. To address local waste issues at the hospital, we’re going to use that grant to remove silicone waste for recycling. Ideally this entire initiative will transcend beyond silicone recycling as hospitals also generate lots of plastic waste contributing to carbon emissions. Similarly, we hope to extend these efforts beyond Vanderbilt to other areas to drive impact. I’ve been exploring venues and initiating conversations about a small start-up that aims to provide hospitals with waste reduction methods. Implementing sustainable practices in medicine is invaluable, and I am committed to broadening the impact of this project,” said Saad.

Saad will have the opportunity to present data at the American Society for Plastic Surgeons Meeting in Austin, Texas, this October. She hopes to inspire institutions to follow her lead in recycling silicone. While she feels medical professionals might still need additional incentives to take action, she is confident that recycling silicone can serve as an effective starting point for introducing new environmental sustainability methods in hospitals to reduce overall waste.

Some comments have been revised for clarity.