Spinal cord and traumatic brain injuries impact millions of people worldwide. These injuries cause neuronal loss and the formation of scar tissue, which is believed to block the regrowth of axons—thin nerve fibers that carry electrical signals. As a result, recovery is limited, often leading to lasting impairments that affect patients’ autonomic, motor, and sensory functions and greatly diminishing their quality of life. Current treatments for brain and spinal cord injuries are largely inadequate, focusing on supportive care rather than the ideal: regeneration.

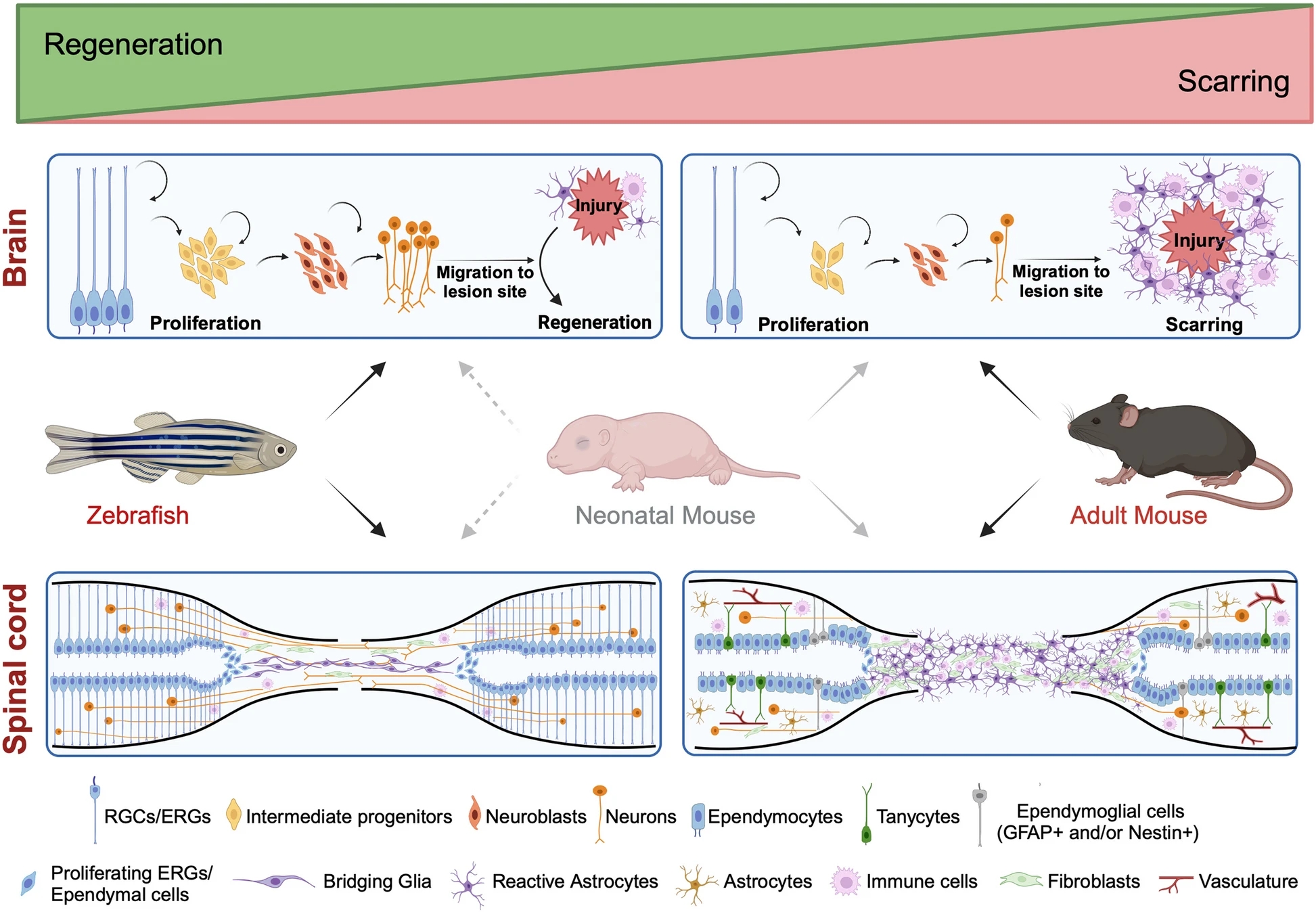

Unlike adult mammals, which exhibit limited regenerative capacity, certain animals such as zebrafish and neonatal mice possess the remarkable ability to spontaneously regenerate both brain and spinal cord, even recovering functions like motor control after paralysis. A recent review from the lab of Assistant Professor of Pharmacology Valentina Cigliola, published in BMC Biology, emphasizes the urgent need to understand the mechanisms that enable this innate regeneration and why adult mammals lack it.

The paper offers the first direct comparison between regenerative mechanisms in zebrafish and neonatal mice, compiling data on the specific signaling pathways, cell types, and epigenetic mechanisms that promote neurogenesis, axon regeneration, and synaptic integration in both models.

Zebrafish, with their robust regenerative capacity and extensive genetic toolkit, and neonatal mice, with their transient, post-birth regenerative window and relevance to humans, each provide unique insights. Together, their study provides a valuable foundation for advancing regenerative medicine strategies aimed at restoring function after central nervous system injury.

Cigliola, who uses zebrafish and neonatal mice to explore ways to “awaken” spinal cord regeneration in adult mammals, explained in the paper that the implications of this work extend beyond traumatic injuries: Understanding these innate regenerative mechanisms could inform strategies for treating a range of neurodegenerative diseases, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, and spinal muscular atrophy

“Elucidating innate regeneration mechanisms in these animal models and understanding how and why they are lost in adult mammals will contribute to the development of strategies to promote central nervous system regeneration in humans,” Cigliola said.

By deciphering why animals like zebrafish and neonatal mice—but not adult mice—can regenerate, Cigliola’s team aims to develop innovative therapies that restore function in the human central nervous system. Such advances have the potential to dramatically improve outcomes and quality of life for patients living with brain and spinal cord damage.

This review was featured in the “From aging to regeneration” section of the “A year of stem cell and developmental biology” Nature Portfolio Collection.

Funding

This research used funds from the French National Research Agency, Vanderbilt University, and the Vanderbilt Brain Institute.