By Chuck Sanders, Vanderbilt University, and Alfred L. George, Jr., Northwestern University

Chuck Sanders and Dr. Al George started collaborating on ion channels and related diseases in the mid-2000s, work that continued after George moved from the Division of Genetic Medicine in Vanderbilt’s Department of Medicine to his present position as Chair of Pharmacology at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. We join the conversation of these two old friends.

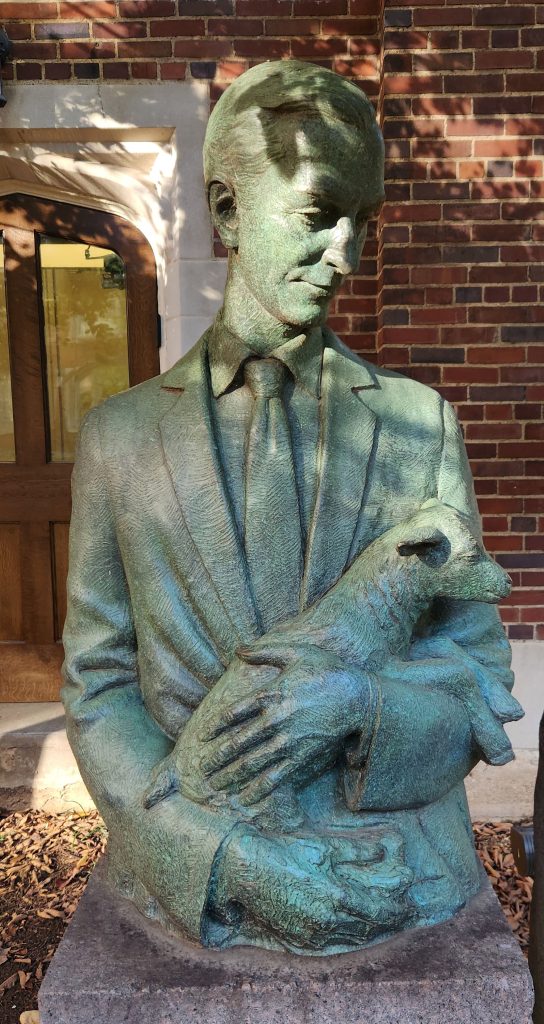

Chuck: Hi, Al! So, in the courtyard between my building here at Vanderbilt and the old Medical Center North building, a sculpture recently appeared of a very kindly-looking gentleman holding what appears to be young lamb. There is an almost-Biblical “good shepherd” quality to it. However, I learned that this is a special person and he is not holding a lamb at all! It is Dr. Virgil LeQuire, the father of Nashville’s most distinguished extant sculptor, Alan LeQuire. Alan is the artist who did the scary, 40-foot-tall statue of the goddess Athena located inside Nashville’s full-scale replica of the Parthenon. He also did the sublime Tennessee Woman Suffrage Monument located in the same park as the Parthenon. Virgil LeQuire was a professor of anatomy and pathology at Vanderbilt from 1949 all the way into the mid-80s. In this statue, he is actually cradling a young goat, and not just any goat: a fainting goat. I have heard a number of stories about Tennessee’s fainting goats but only know a little. However, I know you are an expert! Can you tell us what a fainting goat is?

Al: Hi, Chuck. Thank you for telling me about the statue of Dr. LeQuire. He was an important person at Vanderbilt, having been a professor of pathology for many years and the director of admissions for the medical school. I knew him best for his love of fainting goats. These curious animals got their name because, when startled, they fall over. But despite their name, they don’t actually faint or lose consciousness. In fact, they fall over because their muscles get stiff and they lose their balance. It’s a congenital problem with genetic roots. In addition to being known as fainting goats, they have been called stiff-legged goats and nervous goats. Medically speaking, they are myotonic goats.

Chuck: With the help of some articles you sent I did some reading into the origins of the fainting goats. It looks like their origins in Middle Tennessee date back to roughly 1880, when a man appeared in Marshall County with four fainting goats and a sacred cow. The stranger was said to wear two different hats, eventually sold the goats to the local M.D., and then disappeared, taking his sacred cow with him. As best as we can tell, these goats were the start of a herd that then proliferated and spread to several other Tennessee counties. They are first mentioned in the scientific literature in 1904. What do you think of this origin story, Al?

Al: I’m familiar with this folklore and have no reason to doubt the tales of the origins of fainting goats in Middle Tennessee. Certainly, folks in that area are proud that these special beasts were first described there. If the original goats were bred with local animals, then the genetic trait would have been passed down generations. Virgil told me once that his neighbors got mad at him when his goats escaped and romanced the neighbor’s herd, because the following year they birthed fainters. I think Gregor Mendel would have found that more interesting than pea plants.

Chuck: I have to say that I am even more intrigued by the magic cow than by the goats; I guess the properties of that heifer are forever lost in the hallways of time. Anyways, the fainting goats eventually achieved some degree of prominence in the history of genetic disorders. Were the fainting goats a mere scientific curiosity, or do they have a special place in the history of genetic medicine?

Al: Indeed, I would like to know what happened to that magic cow. Maybe that was the origins of chocolate milk. Yes, the fainting goats were not just part of the local folklore, but they provided a natural animal model of the human disease myotonia congenita, an inherited disorder of muscle. Physiological studies of muscle obtained from fainting (myotonic) goats led to discoveries that later explained the pathophysiology of myotonia and inspired the successful search for the causative gene in humans.

Chuck: As a physician-scientist, can you tell us a little more about the exact symptoms of myotonia?

Al: Myotonia is the term used to describe an impairment in relaxation of skeletal muscle. Normally, after muscle contacts it can relax briskly. However, in myotonic muscle the relaxation phase is slow, and this results in persistent contraction. Myotonia congenita can be evident in early life, sometimes soon after birth. Parents sometimes describe their newborn child as having muscles like Hercules, which suggests some degree of muscular hypertrophy that can accompany myotonia. They also report stiffness of arms and legs when babies are moving. Later in life, people with myotonia congenita experience muscle stiffness when they first start moving after a period of inactivity such as sitting for a long time. The stiffness is most pronounced for the first several seconds, then improves with continued movement. This is called the ‘warm-up’ phenomenon, but there is probably no change in muscle temperature to explain the effect. Some people with this condition sometimes don’t recognize they are different from others when it’s mild. Myotonia congenita is not life-threatening and not progressive like muscular dystrophy. It is typically associated with a relatively normal life and reproductive fitness. That is why it can be inherited. Because of the mild muscular hypertrophy, some young men with the condition are selected for sports but soon find out that they can’t move quickly in some situations. For example, I’ve heard that playing baseball is particularly tricky for young men with myotonia congenita. They can hit the ball a mile but can easily be thrown out at first base.

Chuck: Virgil LeQuire did research on the fainting goats, publishing his final papers on this topic in the early 80s. By that time, they knew an awful lot about myotonia in both goats and humans but still had not uncovered the molecular basis of the disease. It is interesting to me that Dr. LeQuire seems to have stopped doing research on these goats but nevertheless maintained a small and carefully bred herd all the way up into the 1990s, at which point you came into the picture as a young professor in Vanderbilt’s School of Medicine. Tell us about your work and how you obtained the fainting goat that you needed for your work.

Al: At the time I moved to Vanderbilt, we were already searching for the human gene for autosomal dominant myotonia congenita. While working on a grant proposal early in my career, I read a review article about the myotonic goat and discovered the authors credited “V. Lequire, Franklin, TN” for supplying the animals for their research. I immediately researched this lead and found Virgil’s name and phone number in something called a phone book (yes, we are OLD friends). I called him and he graciously invited me to his farm to demonstrate the phenotype. A few years later, he donated a goat from his precious herd to my lab for research. Having never worked on any living animal before, I sought advice from a veterinarian in the Vanderbilt animal-care enterprise. They helped us anesthetize the goat to allow us to excise a bit of quadriceps muscle from which we isolated RNA and made a cDNA library. By then, we already knew the human gene for myotonia congenita was CLCN1, which encodes the muscle chloride channel ClC-1, so we knew where to look. Of course, there was no reference goat genome to guide us, but we managed to use degenerate PCR primers to amplify goat ClC-1. To complete the work, we had to find a control goat that didn’t have myotonia. Fortunately, the local newspaper (not online by the way) had a lengthy classified ad section that listed goats for sale. Thanks to a local breeder, we had our control and quickly identified a missense variant in the fainting goat. That variant, Ala885Pro, was then functionally characterized and found to exhibit loss-of-function effects consistent with the disease. You can read all about it in our PNAS paper from 1996.

Chuck: Am I the only one who finds it remarkable that Virgil LeQuire continued to maintain that herd long after his own research on fainting goats had been completed?

Al: I’m glad he did! I truly believe he loved these animals. His son’s depiction of him lovingly holding the baby goat was probably accurate. He was fond of his herd.

Chuck: My understanding is that the Ala885Pro mutation alters the voltage regulation of the ClC-1 chloride channel, such that it remains in a low conductance state when it needs to be in a high conductance state to maintain a normal resting electrical potential in muscle tissue, right? The ClC-1 channel structure was determined relatively early in the modern history of membrane protein structural biology. Has the structural basis for how the Ala885Pro alters the voltage-dependence of ClC-1 ever been determined?

Al: The structure of ClC-1 was determined and it’s fascinating. I don’t believe anyone has investigated the structural perturbations associated with this particular mutation, but that would be interesting.

Chuck: Are there human patients with the same Ala885Pro mutation?

Al: Not to my knowledge, but ClinVar has an entry for another amino acid substitution of this same codon (Ala885Ser). However, other human pathogenic CLCN1 variants exhibit similar functional disturbances as what we observed for the goat mutation.

Chuck: As a pioneer in ion channel genetics, maybe you can educate me on a matter of semantics. When should a point mutant form of a gene or protein be referred to as a “mutant” and when should it be described as a “variant”?

Al: This is a valuable question. Any difference in nucleotide sequence could be called a variant. Most variants in humans have no known medical consequences. The small subset of disease-causing variants could be called mutations, but nowadays geneticists like to use the term pathogenic variant to distinguish these from non-disease causing or “benign” variants. The old term “polymorphism” is still hanging around but is really disfavored. We also use terms such as “common variant” and “rare variant” to describe variants by their frequency in the general population. I think we moved away from referring to disease-causing variants as mutations because people with such variants should probably not be thought of as mutants. It’s probably fine to refer to proteins or animals with pathogenic variants as mutants. They won’t care as much.

Chuck: Well, I suppose it is about time for us to wrap up. Can I ask you to tell me something that you are thankful for this year?

Al: I’m thankful that I was afforded the opportunity to engage in research for my career and am most thankful for my great colleagues and collaborators such as you. That’s what makes doing science rewarding and fun. Thanks for the chance to discuss this topic.

Chuck: Agreed! We have lived charmed lives, and I just hope and pray that the emerging generation of scientists—our students, postdocs, and junior faculty—will have access to the same wonderful opportunities we have benefited from.

Acknowledgements

We thank Becky Sanders for proofing this conversation. You can see fainting goats in action by doing a Google video search on “fainting goats.” A slightly edited version of this articl

e was posted in The Protein Society newsletter Under the Microscope. We wish you a very happy U.S. Thanksgiving!