Cancer has been called “the emperor of all maladies.” Professor of Cell and Developmental Biology William Tansey calls MYC, in turn, “the emperor of all oncogenes.”

He and Professor of Biochemistry Stephen Fesik are employing MYC, pronounced “mick,” to seek out cancer’s Achilles heel. By pioneering a unique strategy to make the long-undruggable MYC vulnerable, Tansey and Fesik are rewriting the playbook for defeating cancer. And after ten years of research, the two School of Medicine Basic Sciences investigators are preparing to advance a cancer drug to clinical trials.

Both Tansey’s and Fesik’s backgrounds have set them up perfectly for this task. Tansey has been studying gene regulation and oncoproteins—proteins encoded for by oncogenes, mutated genes that can contribute to the development of cancer—since his postdoc days at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York in the 1990s. Fesik, who is internationally known for structural biology research and cancer drug discovery, was the divisional vice president of Cancer Research at Abbott Laboratories, where he built a pipeline of anti-cancer compounds prior to joining Vanderbilt in 2009.

MYC proteins are transcription factors pivotal for normal cellular processes, such as cell growth, division, and differentiation—and for cancer progression. Like other transcription factors, MYC binds to DNA sequences near target genes, regulating their expression and influencing cellular behavior. Dysregulation of MYC can result in uncontrolled cell growth and tumor formation, a defining characteristic of cancer.

“MYC is unusual in that it is involved in a lot of cancers, including blood, colon, brain, lung, breast, and prostate cancer,” Tansey said. “It's responsible for approximately one-third of all cancer deaths.”

The solution seems simple: Turn off MYC to stop cancer in its tracks. There’s only one problem—MYC lacks a defined structure and therefore it’s thought to be undruggable. Most proteins have a defined shape, a three-dimensional architecture with contours to which small chemicals can be attached. If a protein target does not have a defined three-dimensional structure, you can't drug it. MYC is an intrinsically disordered protein, like a constantly shape-shifting noodle. A slippery beast.

So, if you can’t target MYC, what can you do? Tansey and Fesik are shifting their attention away from the undruggable MYC to something that can be drugged: the structured protein WDR5, a partner in crime for MYC.

A partner in crime

WDR5 participates in numerous cellular processes, including transcription, DNA repair, and cell division, and, luckily for medicinal chemists, has a well-defined structure.

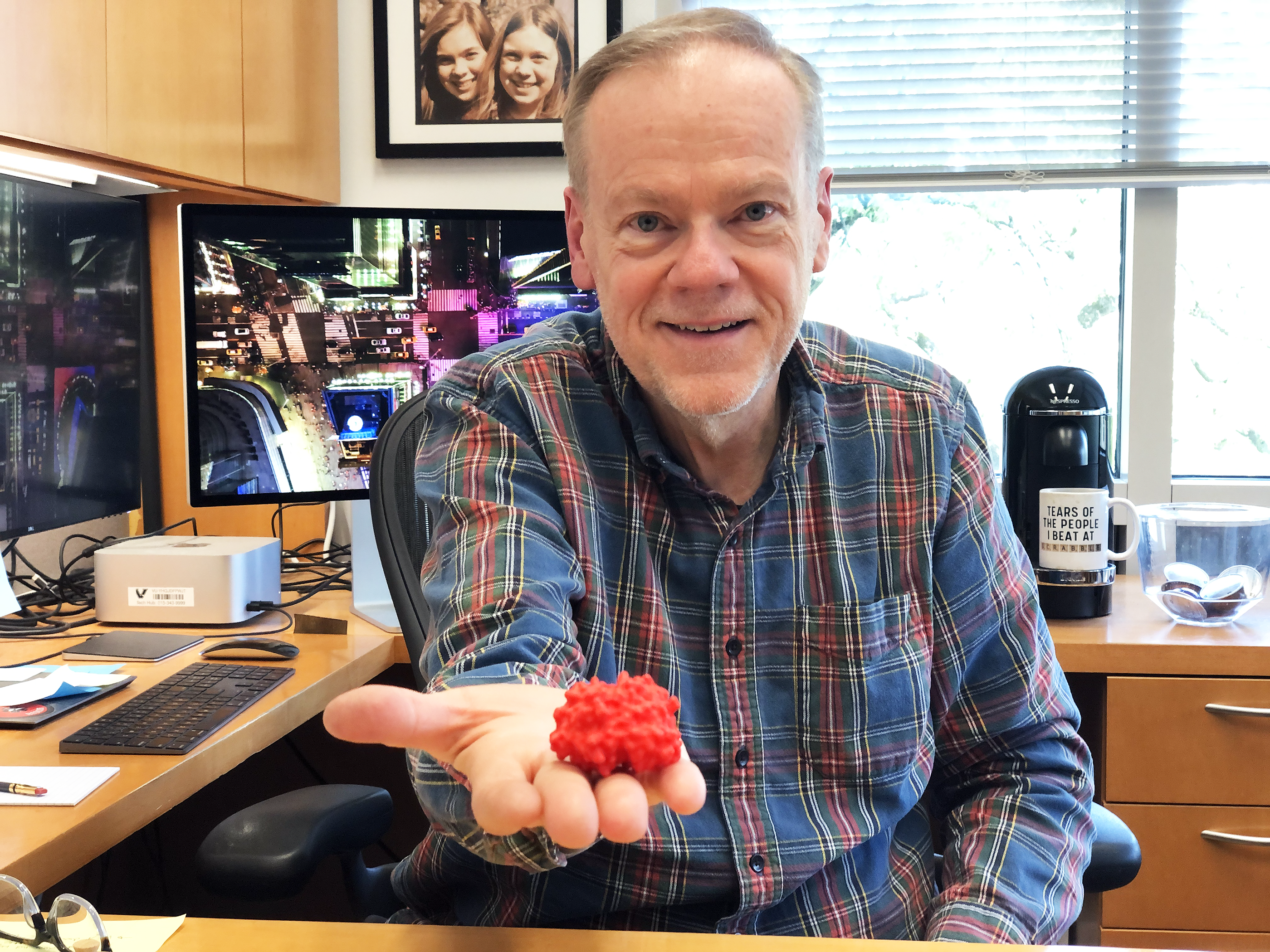

Tansey’s lab discovered WDR5 in 2013 and determined that it played a role in MYC biology. Rapidly growing and dividing cancer cells have a strong appetite for increased protein synthesis, and Tansey found that MYC “absolutely depends on WDR5” for it. He approached Fesik, who had ample expertise in identifying compounds that bound to proteins and turning them into drugs, and asked, “Would you like to drug it?”

Fesik had a one-word response: “Absolutely.”

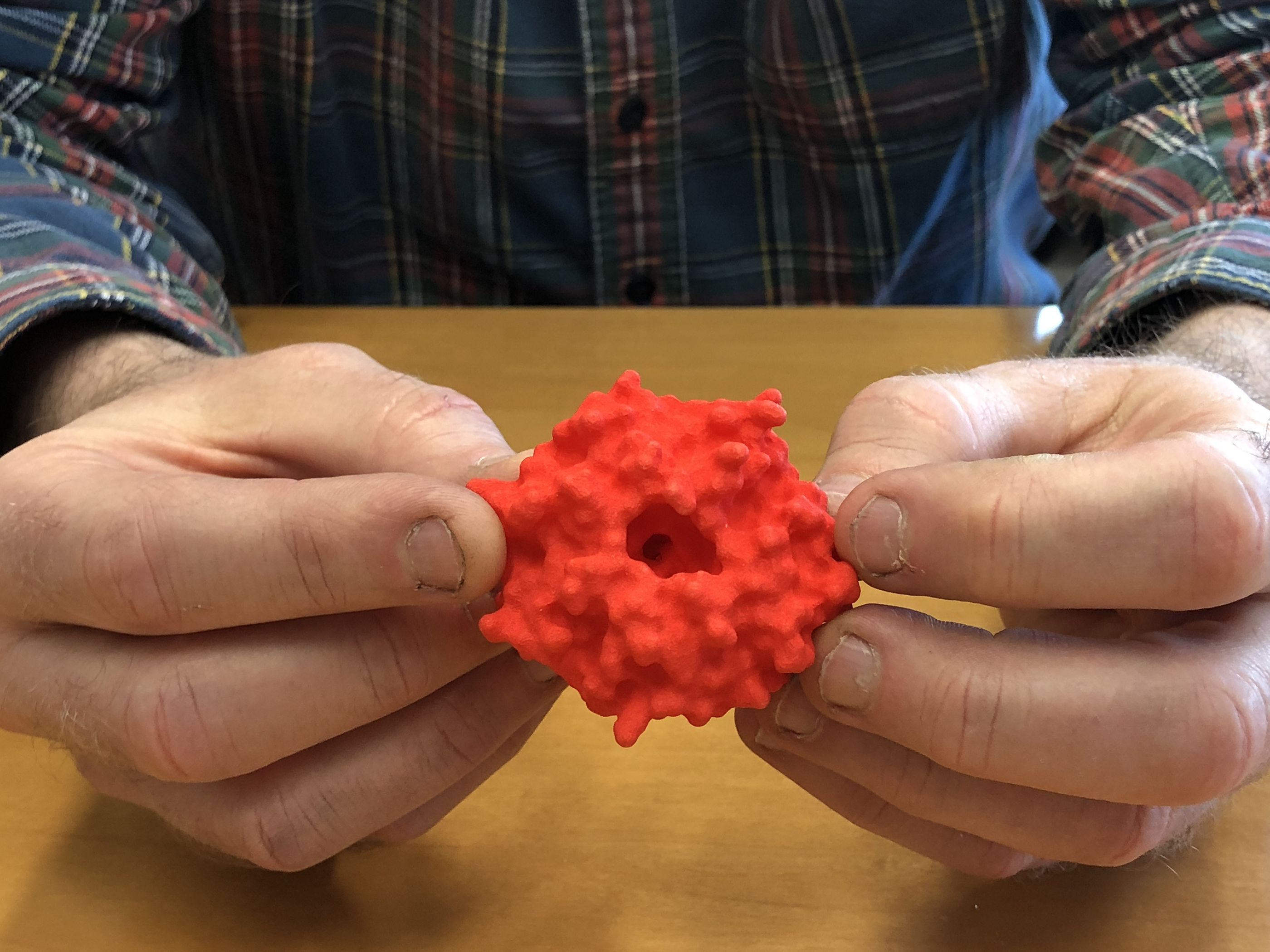

Tansey had discovered that MYC binds to WDR5 and that this interaction was required for MYC-driven tumor development. He and Fesik knew, based on the scientific literature, that there are two sites on WDR5 that could be focal points for drug discovery, the “WBM” and “WIN” sites.

The pair decided to try to inactivate WDR5 with a drug that attaches to the WIN site. WIN site inhibitors would block the interaction between WDR5 and other proteins at the WIN binding site, disrupting WDR5’s function and potentially leading to anti-cancer effects.

Since he began working with Tansey, Fesik and his lab have identified a number of small molecules that bind to the WIN site through the use of fragment-based drug discovery. FBDD involves testing huge libraries of small chemical compounds against a target, such as WDR5’s WIN site, to see which ones bind best, and use them as a basis upon which to “build” a new and improved compound for your needs. Following FBDD, Fesik’s lab makes the identified molecules extremely potent using structure-based design processes.

“Our molecules bind the WIN pocket and pop WDR5 off the chromosome, and MYC comes off with it, essentially cutting off its ability to drive protein synthesis,” Tansey said. “Some cancer cells respond to that very badly and die.”

Piecing drugs together

The traditional approach to drug design involves screening a library of relatively large, intact compounds against the desired protein target, so it's harder to find “hits”—compounds that have the potential to change the target’s activity—and those hits don't necessarily bind the target very well. In response to those shortfalls, Fesik pioneered, refined, and has applied FBDD to many proteins for nearly 30 years. Using libraries of fragments instead of larger compounds means that the fragments have a better chance of tightly binding a target protein, and drugs built out using those fragments tend to have better physiochemical characteristics.

To find “lead” molecules that can be turned into drugs, the Fesik lab uses nuclear magnetic resonance to screen for fragments that bind to a binding site. After identifying hits, the researchers create a three-dimensional structure of the protein bound to the drug fragments using X-ray crystallography, which provides a picture of how the fragments fit into the protein’s binding site and how they might be linked together. In what’s a very modular approach to drug discovery, the fragments are then assembled into a larger molecule that better fills up the target protein’s binding pocket.

Hitting cancers where it hurts: MYC

Using an FBDD screen, Fesik’s lab discovered potent compounds that bind to the WBM and the WIN sites of WDR5. They used these compounds as tools with which to study the biology of WDR5 and evaluate WDR5 as a cancer drug target. Their findings indicated that a WDR5 inhibitor could be useful for treating a wide range of cancers. After extensive further study, they discovered WDR5 inhibitors that are safe and can be administered orally and absorbed into the bloodstream with a therapeutic effect in animal models.

Fesik and Tansey’s very expensive WDR5 drug discovery research was funded by the National Cancer Institute’s Experimental Therapeutics Program, a program started by the NCI to encourage drug discovery in academia. Thanks to their NExT grant, the Fesik lab has produced and tested approximately 1,500 chemicals and selected a lead candidate. Eventually, he and Tansey hope to bring this candidate to the clinic, but they must complete Investigational New Drug–enabling studies, essential preclinical tests needed prior to human clinical trials, before they can do so.

After ten years of preclinical drug development, Fesik and Tansey are ready and are working with the NCI to move their chosen WDR5 inhibitor into IND-enabling studies. Their main objective will be to collect thorough preclinical data that illustrates its safety for initial human use and confirms its pharmacological activity, both of which will determine if the compound warrants further development as a drug.

What’s next

As Fesik and Tansey prepare to take their groundbreaking research into clinical trials, the entire medical community stands on the brink of significant advancement in cancer treatment. With a focus on discovering potent WDR5 inhibitors and disrupting MYC’s activity, they aim to cut off cancer’s lifeline by targeting its fundamental hunger for protein synthesis.

These promising advances might just be game changers in the fight against cancer.