M1 Darryl Delsoin joins the Medical Innovator Development Program (MIDP) with an entrepreneurial mission

By: Lexie Little

Darryl Delsoin peered through the white smoke cloud. He watched as local Haitian women and men cooked over ash-riddled round stoves fueled by charcoal. Nearby wooden doorways, some stained with soot, stood as the divide between fresh air and the noxious byproduct of burning coal: indoor air pollution, which exposes families to harmful toxins and pollutants like carbon monoxide.

Delsoin thought about what his entrepreneurship mentor at Berry College in Mount Berry, Georgia, had said to him.

“Go back home for the summer and really analyze what the problems are,” Paula Englis, a professor of management, said to him.

He found a problem.

In Haiti, Delsoin’s home country, more than 90 percent of households use charcoal or wood as cooking fuel. The World Health Organization notes more than three million people worldwide die prematurely from exposure to indoor air pollution.

He considered the adverse effects on the lungs, the heart, and overall health of his fellow citizens who his mother, a dermatologist, served as Minister of Public Health and Population in Haiti from 2016-17. Following her through an infectious disease clinic years before, he had seen first-hand disproportionate effects in public health. Those patients and the clinic conditions inspired his own desire to become a physician.

“I saw how physicians were working under not great conditions: the clinic was overloaded, it was hot all the time, they have few resources, and they were often threatened when they headed off to work because of civil unrest,” Delsoin said. “They still showed up every day to work. So that was my first impression of physicians, people who actually want to make change in the community. That was my first introduction to medicine, and that’s why I want to be a doctor – not necessarily because of my mom but because she introduced me to that world. My mom became involved in public health in Haiti and served as minister of health for some time…Whatever she set her mind to, she would say, ‘Oh, I want to do this,’ and the next thing I knew, she was on TV talking about it. I thought it was so cool. She had a positive impact on my journey and what I want to do, for sure.”

With a mission in mind, Delsoin traveled to the United States for undergraduate studies as a biochemistry major following a pre-medical track. While at Berry, he gained an interest in entrepreneurship, which led him to a course with Englis. Back home, the flames of those cooking fires sparked an idea: he would find a way to provide clean cooking fuel for Haitian families.

Converting passion into success

Through a process known as biomethanation, organic waste converts into biogas, a clean cooking fuel. By operating biomethanation plants, Delsoin could provide clean fuel, work toward reducing deforestation needed for solid fuels, and create a natural fertilizer (processing byproduct) that could be sold to offset costs.

“I knew I wanted to do something in the area of public health and health equity,” he said. “I went to the business school at Berry, and said ‘Hey, I am a biochemistry major, but I am interested in entrepreneurship, and I want to do something in this space’…I went back home, tried to be perceptive to what was wrong, and I realized people were cooking with charcoal, and there was a lot of smoke. I thought, ‘That can’t be good for health.’ I started doing my research about that issue and what technologies are out there to prevent people from cooking with firewood and charcoal. And that’s when I read about biomethanation. I said to myself, ‘That’s super cool, but why is it not a thing in Haiti and so many other countries? How can I do something about that?”

At a 2021 entrepreneurship competition at Berry, Delsoin proposed a nonprofit model to fund purchase of biomethanation plants to help Haitian families. Students presented ideas to a panel of judges who then awarded grant money to start initiatives. Delsoin’s nonprofit, Resinab, earned $10,000.

Initially, the work ahead seemed daunting. As a biochemistry major, Delsoin had never imagined starting a nonprofit with operations in the United States and Haiti. But now, he and his team – colleagues he met in college – plan to obtain 501(c)(3) nonprofit status in the U.S. while providing biogas to 50 individuals. Delsoin hopes to secure 20 more biomethanation plants to triple that number when he can safely install them in Haiti.

“[The logistics were] a big concern when I got this grant,” he said. “It was a big grant at Berry, and I thought, ‘Oh, you’re giving me that much money for a plant I have no idea how to start?’ That was stressful. But I knew the end goal would be beneficial to a lot of people, and that kept me going. Starting a nonprofit is probably the most significant milestone in my career so far because of my background. If you’d asked me four years ago if I would ever start something in the business world I would have said, ‘No, no. I’m going to be a doctor. I just know chemistry and biology. That’s about it.’ Hearing myself talk about a business model and 501(c)(3), that’s super cool. I have a growing passion for entrepreneurship.

But I’m also proud of getting into medical school. That was an exciting time.”

Seeking to solve the next problem

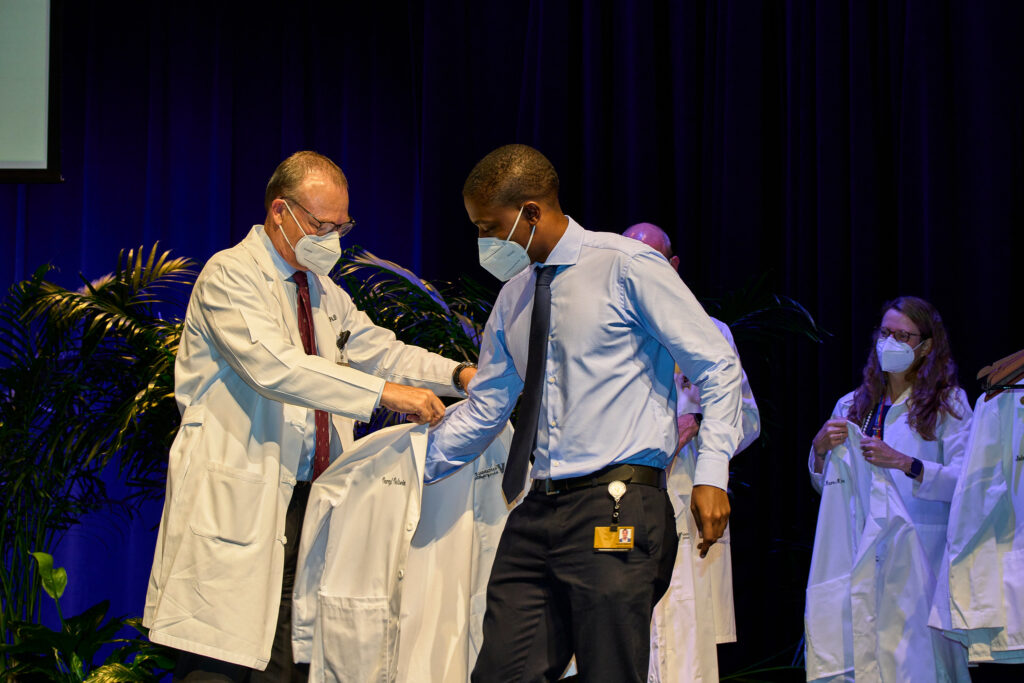

On July 22, 2022, Delsoin stood in the shade of Light Hall across from the main hospital at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. He watched a swirl of white cover the plaza. But it wasn’t smoke. His first-year MD classmates, clad in short white coats, gathered for pictures after the annual White Coat ceremony.

His family came to celebrate his welcome into the medical profession. He looked over at his mother, smiling. She achieved a dream that day, too: visiting Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Dr. Delsoin had once worked with a contingent of Vanderbilt University AIDS and infectious disease researchers and health care professionals that participated in a special training program.

“I knew about Vandy way before I ever got to college,” he said. “That was one reason I came here. Vandy helped to form a group of physicians in Haiti to work in infectious diseases. My mom was always telling me, ‘That’s a great institution.’ I worked really hard for medical school. When I got in, I knew a lot about the program already. That was a plus. Vanderbilt was my first choice. When I got my letter, I said, ‘Okay, I’m going.’ It was early in the admissions cycle, but it didn’t matter what came next.”

Arriving at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine (VUSM), Delsoin knew to expect many opportunities based on the school’s reputation for collaboration and service. Not knowing exactly what possibilities awaited him, he planned to take full advantage of programs offered. Then, he heard about the Medical Innovators Development Program (MIDP), which trains future physician innovators through a specialized MD curriculum focused on deep clinical understanding and biomedical innovation design.

Delsoin gained familiarity with clinical medicine through shadowing opportunities, but he knew he wanted more from his career. When he learned about MIDP and the ability to extend clinical training into an entrepreneurial space, he knew he should join the program.

“When I found out about MIDP and the chance to combine entrepreneurship with my passion for medicine, I thought it was really neat,” he said. “Coming to the U.S., I didn’t know exactly how clinics work here. I’ve had some shadowing experience, but that doesn’t mean I know how everything works; the systems are complicated. MIDP offers a learning experience where I can identify the problems and be innovative in that multifaceted and complex system. I’m not exactly sure what I want to do after medical school, but I know I want to do things that address problems at a systemic level. I know I want to work at a clinic, but I also want to work on initiatives that can be incorporated in many clinics across many cultures.”

Delsoin now plans for a career that combines innovation and clinical work, perhaps in infectious disease or a pulmonary or cardiology specialty area inspired by his previous work to combat cardiovascular disease via smoke inhalation. However, he keeps his mind open to new possibilities. He never knows where he’ll find a problem to solve.