Established 52 years after the university, the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine has been conducting innovative biomedical research for almost 100 years. It has witnessed social progress, infrastructure development, and expansion alongside the university and Nashville itself.

By Larry Marnett and Stephen Doster

The School of Medicine Basic Sciences is a unique entity among schools of medicine in the United States. It bridges Vanderbilt University and Vanderbilt University Medical Center and has a mission to advance discovery science and Ph.D. training in the biomedical sciences. At a time when many schools of medicine are reducing their commitment to basic science, how did our school come about?

In the beginning

In 1849 the Tennessee State Legislature passed a bill establishing the Medical College (owned and controlled by its medical faculty) as part of the University of Nashville. The first session of the Medical College opened in 1851 with 121 matriculants. The campus stood on Rutledge Hill, south of downtown Nashville.

Vanderbilt was established in 1873 on 70 acres west of downtown Nashville. A year later, the Vanderbilt Board of Trust and the Medical College arranged for the creation of a medical department serving both Vanderbilt University and the University of Nashville, which allowed students to choose which school issued their diplomas.

In 1908, the Flexner Report, commissioned by two national organizations with a mission of improving health care in America, recommended a drastic reduction in the number of medical schools and the creation of science-based medical training, and recognized the need to fund a new medical school in Nashville.

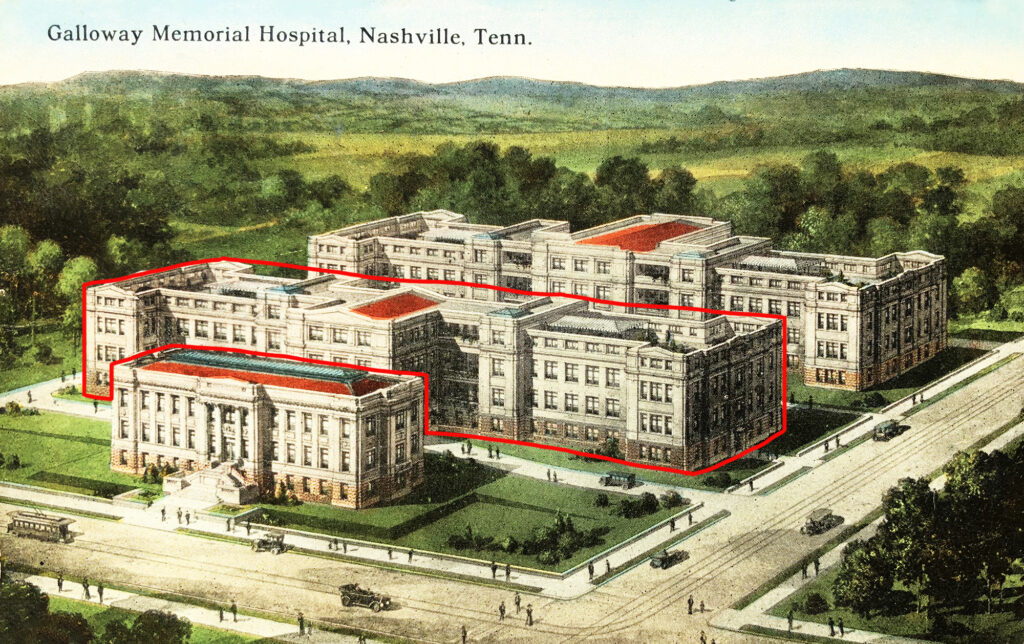

Vanderbilt Chancellor James Kirkland secured $4 million from the Rockefeller Foundation’s General Education Board in 1919 and hired Dr. Canby Robinson as dean. Robinson and others lobbied to build a new medical school on Vanderbilt’s west campus, along 21st Avenue, as opposed to the Rutledge Hill/south campus location that Kirkland initially wanted. It was designed by Boston architect Henry R. Shepley as a structure that, for the first time in this country, would house under one roof all the facilities needed for the laboratory and clinical training of students and the research of their mentors.

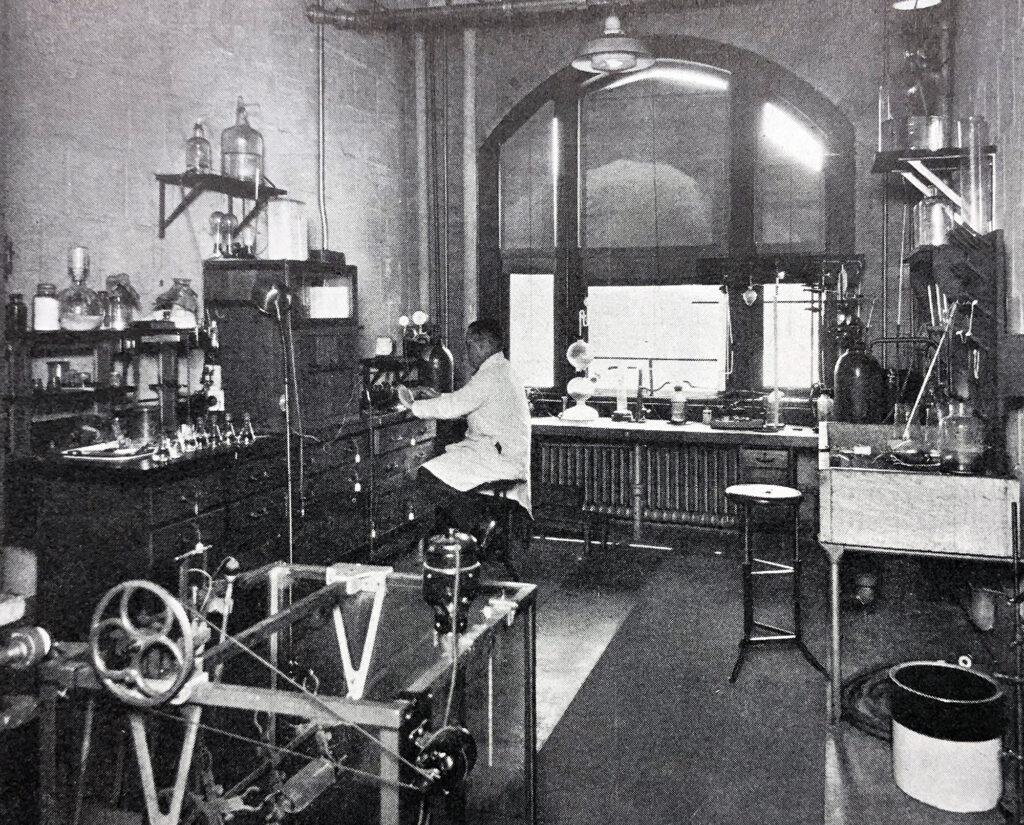

Finally, 52 years after its founding, Vanderbilt opened its own medical school in 1925. To support science-based training, the administration established departments of anatomy, biochemistry, pharmacology, and physiology, which evolved over time into our current departments: biochemistry, cell and developmental biology, pharmacology, and molecular physiology and biophysics. Weekly journal clubs kept students and faculty abreast of research literature, departments and clinics collaborated on research projects, and graduate students received their degrees from the university instead of the medical school—as they do today.

Moving the Vanderbilt medical school from downtown Nashville to the university campus resulted in its close integration with the university. As the university grew, the medical center came to occupy the center of the campus, surrounded on three sides by the schools of engineering, arts and science, and education. This unique geography established a highly effective platform for collaboration across the university. The medical school developed a strong faculty that included members of the National Academy of Science and National Academy of Medicine and two recipients of Nobel Prizes—Earl Sutherland and Stanley Cohen. Interdisciplinary centers arose that involved faculty from many different departments and schools and not only served as foci for research but were also the homes for training programs for Ph.D. students, M.D. students, postdocs, and residents. Such centers ingrained collaboration as a distinguishing characteristic of Vanderbilt, which has been leveraged repeatedly over the years.

The VU-VUMC reorganization

Despite having developed into a powerhouse for research and training reinforced by trans-university collaboration, VU and VUMC reorganized into separate entities in 2016. The financial crisis of 2008 drastically changed the economics of health care delivery and put significant financial pressure on academic medical centers, which complicated their financing and governance when located within a university structure.

Within such a structure, the resources for biomedical research and education—both medical and graduate—originate from the financial performance of the medical center. As clinical margins tightened, medical centers struggled to adequately invest in research and training, which was particularly challenging for basic science departments and led in some cases to the elimination of departments or the fusing of multiple departments into single mega-departments.

Consequently, after careful deliberation, on April 30, 2016, the Vanderbilt Board of Trust split Vanderbilt University and Vanderbilt University Medical Center into two separate corporations with two separate governing boards, led by Nicholas Zeppos and Dr. Jeffrey Balser, respectively. Zeppos and Balser were strong proponents of basic biomedical research and, to maintain a strong home for basic biomedical research and education, they helped create Basic Sciences concomitant with the VU-VUMC split. Larry Marnett was named its first dean.

The School of Medicine Basic Sciences

The new school was incorporated into the governance structure of the university—its dean reporting to the university provost—and ceased to directly rely on the clinical margin of VUMC. This structure provides not only an independent home for basic science research and training, but also predictable resources to help support operations, faculty recruiting, Ph.D. student training, and investments in infrastructure. In addition, the university funding model incentivizes the school to be entrepreneurial in its approach to revenue generation.

Basic Sciences is responsible for all Ph.D. education within the School of Medicine. Students are recruited mainly through two umbrella programs and join one of 11 graduate training programs after their first year. Faculty from across the School of Medicine and other schools participate in Ph.D. training, which represents a major unifying force among the faculty. All training programs are coordinated through the Office of Biomedical Research Education and Training, and all supporting work for the school occurs through administrative pods.

The first year following the separation was challenging because of the absence of existing structures and procedures, which were developed “as the plane rolled down the runway.” In the years since, Basic Sciences has overcome challenges ranging from business difficulties related to the university’s adoption of a new general ledger to unprecedented trials related to a worldwide pandemic. Faculty and staff have worked tirelessly to develop and accommodate new processes and proved resilient in the face of massive challenges.

Seven years post-separation, Basic Sciences has emerged with an independent identity and has excelled in faculty recruiting, grant funding, and fostering of collaborations with faculty in the schools of engineering, arts and science, and education. Basic Sciences has the second largest budget in the university and accounts for 40 percent of the grant funding at Vanderbilt. The anticipated financial stability has been realized, serving the school well during the financial roller coaster experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

To be sure, there are remaining challenges associated with the bifurcated structure of the medical school, and Basic Sciences will confront them as a new post-pandemic normal sets in. Over the past nearly 100 years, VU and VUMC have leveraged their unique geography and commitment to excellence to become one of the top institutions in the world for biomedical research and training. The reorganization of VU and VUMC, including the creation of Basic Sciences, illustrates Vanderbilt at its best: identifying a problem and formulating a solution even if it requires dramatic change, and thinking outside the box. The current structure highlights Vanderbilt’s long-term commitment to excellence in research and education and provides a world-class home for discovery science to drive biomedical innovation and improve human health.