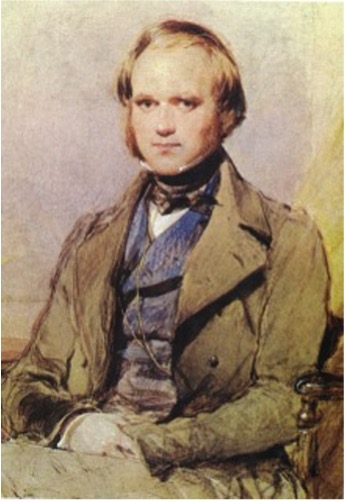

The intrepid CEO of The Protein Society, Raluca Cadar, again used her special Carpathian “connections” to set up our Annual TPS Halloween interview, this year with none other than Charles Darwin. We listen in on his conversation with Basic Sciences Vice Dean Chuck Sanders…

Chuck Sanders: Mr. Darwin, words cannot express what an honor it is to meet you. Thanks for taking the time to share your thoughts on proteins and other topics with us!

Charles Darwin: From one Charles to another, I am pleased to meet you. During my time in the Land of the Living, we knew that proteins existed and were important for life, but the series of key discoveries underlying their true importance and how they are related to the Central Dogma was still many years away. It is only much later—here in the land of What Comes Next—that I have come to appreciate the profound role of proteins in life and the mechanisms driving evolution. It is great that this year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry recognizes both the importance of proteins and the fact that their study remains a frontier area of science.

Sanders: Thanks for saying so! It is notable that while you were collecting the massive trove of data leading the theory of natural selection presented in The Origin of the Species, Gregor Mendel was in his garden in Moravia conducting experiments with pea plants that started the field of genetics. But you did not know about him and his work during your lifetime, did you?

Darwin: Sadly, no. So, all I could do was speculate about the fundamental mechanisms driving natural selection. But Greg and I are now friends; we shoot pool together.

Sanders: Raluca tells me I am not allowed to ask any questions about What Comes Next, so I can’t follow up on this interesting revelation. But let me ask you about your work on barnacles. My understanding is that after you completed the Voyage of the Beagle you spent seven years characterizing barnacles. One of your biographers, Janet Browne, has suggested that it was this very systematic and detailed study that provided you with the intellectual tools to go on to analyze the trove of data that led to an airtight case for evolution. Since your barnacle work largely involved morphological measurements of how one type of barnacle differs from another, I have long thought that you might be able to claim the title of the first structural biologist.

Darwin: What I would have given for a cryo-electron microscope! But this is a good example of “familiarity breeds contempt.” I hate barnacles. Let’s change the subject.

Sanders: So much of your career was inspired by your experience as the appointed naturalist on the five-year voyage of the HMS Beagle, starting when you were only 22 years old. There is another famous beagle in the history of exploration. The lunar lander of the Apollo 10 mission (the final test flight before the moon landing) was named Snoopy, after Charlie Brown’s pet beagle. I’ve long wondered whether the NASA folks intentionally made the connection with the HMS Beagle or whether this was just serendipity. Anyway, I digress. I understand that all through your voyage, you suffered badly from seasickness, right? I’ve been seasick before—you don’t die, but you wish you were dead! I just can’t imagine enduring that for nearly five years!

Darwin: As you moderns say, no pain no gain! Actually, the silver lining is that, because of seasickness, when the Beagle sailed from Brazil to Peru, Captain FitzRoy let me cover much of this route on land, hiking or riding by horse from port to port while the rest of the crew sailed. The exploration of South America and the observations I made there turned out to be absolutely critical to my development as a scientist—amazing geology, flora, fauna, fossils… South America had it all in abundance!

Sanders: It does sound like an amazing adventure. My idea of an adventure is hiking the perimeter of the local golf course!

Darwin: Lions and tigers and bears, oh my!

Sanders: On a profoundly more serious note, while slavery was already outlawed in Britain, you encountered its lingering practice in Brazil, right?

Darwin: My forebears were vocal abolitionists back in the day when slavery was still active in England. Also, my excellent taxidermy tutor was John Edmondstone, a freedman. However, nothing had prepared me for the horror of what I encountered in Brazil and other parts of South America.

Sanders: Particularly in light of this, it is an amazing coincidence in history that you and Abraham Lincoln were born on the same February day in 1809!

Darwin: Yes, Abe is also one of my pool buddies.

Sanders: Wow… Back to the voyage. The Beagle eventually sailed to Australia, where they later named both Port Darwin and the city of Darwin after you. You must be very proud of that!

Darwin: Well yes, I am. However, it was not always that way. Back in the day, an association with Australia was not something a British gentleman welcomed! Thankfully, times have changed, and I am especially thrilled about all of the fantastic science going on Down Under.

Sanders: I have been there, and I can attest to that! I especially would encourage anyone with an interest in proteins to someday coordinate travel to Australia with a visit to the annual Lorne Proteins Conference, not far from Melbourne. Should be on everyone’s bucket list! The Protein Society has a wonderful speaker exchange program with the Lorne folks. Changing the subject again, I find it very amusing that when you were young and trying to decide whether to propose to Emma Wedgewood, you made a list of advantages and disadvantages to marriage. One of the advantages you listed, and I quote, is: “Constant companion and friend in old age… better than a dog anyhow.”

Darwin: That was when I was a young and unenlightened man. Please do note that “better than a dog” was actually a high compliment, coming from me. I love dogs.

Sanders: It is interesting that as a young man you went on that grand voyage, but when you settled down and took up residence with Emma at Down House, you sort of became hobbit-like in avoiding travel.

Darwin: Emma and I had a lot of work to do there at Down House! We raised a large family (including dealing with the loss of three children), and it’s also where I did my barnacles work and later wrote On the Origin of Species. Plus, I was often not feeling very well. I now realize that I almost certainly picked up a parasite or two during the voyage.

Sanders: Your final project was the earthworms project, which led to the book that was your best seller during your lifetime and is still considered an important work in vermeology. The beauty of the project is that your backyard was your laboratory. You apparently had your whole family, including grandchildren enlisted.

Darwin: Yes, what fun it was! The grandeur of life on Earth, even right under our noses, is unbounded!

Sanders: I want to ask you about a story I first heard from an Emma Stone skit on Saturday Live. The story is that you had a pet tortoise, Harriet, and that it lived until just a few years ago and was owned for a while by the Australian TV zoologist, Steve Irwin. True?

Darwin: Hmmm… we did indeed collect several juvenile tortoises from the Galapagos Islands in 1835 and returned them to Britain on the Beagle. However, they were turned over to zoos and museums. I heard rumors that one of the later captains of the Beagle eventually transported one of them to Australia. It is very possible that it later became Mr. Irwin’s pet. These amazing creatures live up to 200 years old! If I see Steve, I will ask him about Harriet.

Sanders: The popular press was pretty rough on you during your lifetime. Was that hard?

Darwin: Yes. But this is where it was good to be anchored by my family at home in Down House. It was a shelter in a time of storm, to borrow a line from an old hymn.

Sanders: My own favorite reference to you in popular culture is a call-out in the R.E.M. song “Man in the Moon.” It salutes your courage as a scientist to pursue the truth even though the implications of the truth were viewed as a threat to long-established societal beliefs about the nature of life.

Darwin: I do know the song, but appreciate that you can’t quote the exact lyrics in polite company! I definitely was not interested in upsetting societal norms, but to misquote Jesus: truth is like the wind—it blows where it will.

Sanders: One last question: If you were invited to a Halloween party, what would you dress up as?

Darwin: That’s easy! I would go as Charlie the Octopus. I always thought that octopi are wondrous creatures and we now know that not only are they very intelligent, they have a nervous system that is set up completely differently than in most animals. A large fraction of octopus neurons are distributed in their tentacles.

Sanders: I would love to see you as an octopus. But I never get invited to the good parties! Alas! It is time to close. Thanks so much for taking the time to chat, I am very grateful!

Darwin: Not at all. Please pass on my regards to your colleagues. Keep up the good work!

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Becky Sanders and Raluca Cadar for their edits. If you would like to learn more about Charles Darwin and the development of the theory of natural selection and evolution I highly recommend Janet Browne’s magnificent two-volume biography Voyaging and The Power of Place. A slightly modified version of this interview is also published in the October 2024 Protein Society Newsletter, Under the Microscope.