Although the genome’s claim to fame is coding for the proteins that make up an organism, there’s a lot more to it than just protein-coding genes. In fact, protein-coding genes make up a much smaller portion of the human genome compared to transcribed noncoding genes. But even though we know that many of our genome’s noncoding genes are misregulated or mutated in different diseases, scientists don’t know the precise roles of most of them.

Gregor Neuert is looking to change that. In a paper published in May in Nature Communications, Neuert and two of his lab members, Benjamin Kesler and John Adams, demonstrate a new process that can help determine the precise mechanism of action that specific noncoding RNAs enact in individual cells, a breakthrough that overcomes the limitations of cell population analysis techniques. Neuert is an associate professor in the Department of Molecular Physiology and Biophysics and has extensive experience in single-cell work. Kesler was a graduate student in the Neuert lab when he conducted this research and Adams is a current research assistant.

Current research has pointed to two main ways in which long noncoding RNAs, referred to as lncRNAs, can regulate gene expression: by acting after getting transcribed (transcript-based mechanisms) or by having an effect while getting transcribed (act of transcription–based mechanisms). The difference between these two broad mechanisms might seem small, but on the molecular scale they are vastly different.

Understanding exactly how specific lncRNAs function can shed light on their roles in physiology and disease. As proof of concept, the recent Nature Communications paper focuses on two RNA transcripts involved in X-chromosome inactivation, the critical process by which one of two X chromosomes is inactivated in female mammals.

We sat down with Neuert to learn more about the study.

What issue/problem does your research address?

This research addresses the lack of mechanistic understanding of long noncoding RNAs and their regulation. Specifically, it investigates how different mechanisms regulate the expression of Xist and Tsix, two antisense lncRNAs involved in X-chromosome inactivation, using a quantitative single-cell approach.

What was unique about your approach to the research?

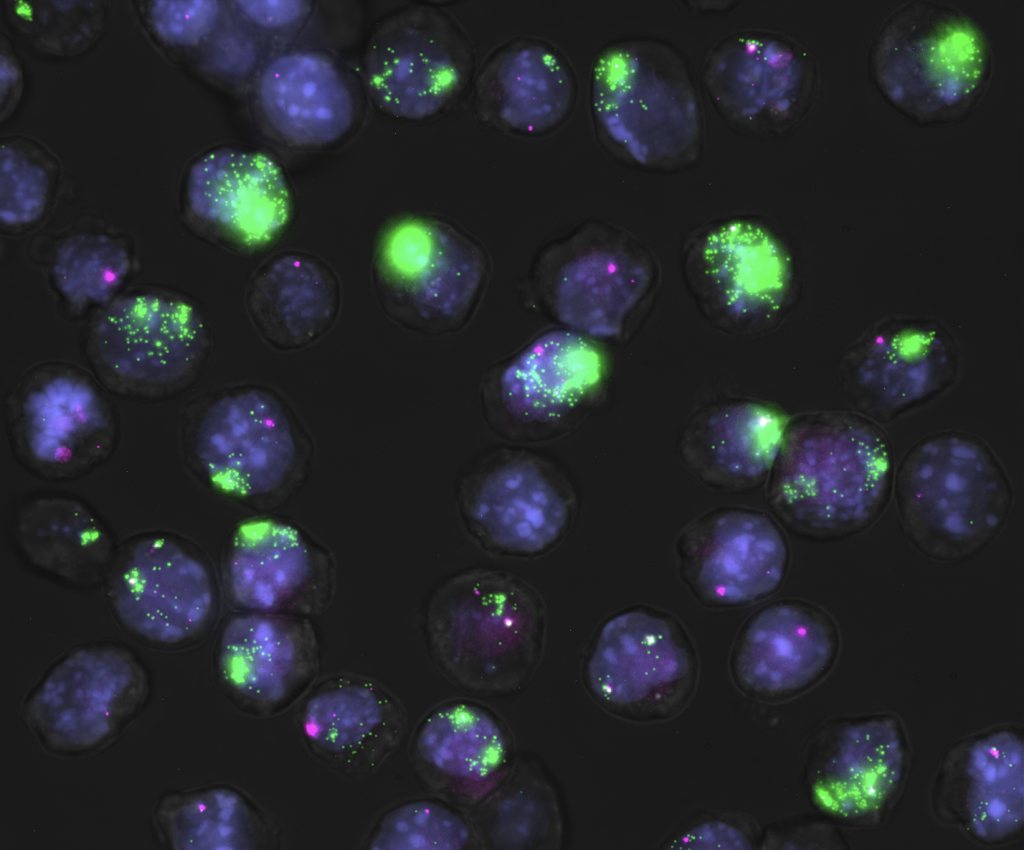

This study simultaneously tested multiple proposed mechanisms for Xist/Tsix regulation in an unbiased manner using single-molecule RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization, referred to as smRNA-FISH; immunofluorescence; and quantitative imaging. The research leveraged natural transcriptional variability in single cells instead of artificial genetic mutations, which reduced experimental artifacts. It provided a quantitative framework that can be broadly applied to other antisense lncRNAs.

For this study, we used Vanderbilt’s Advanced Computing Center for Research and Education for data processing and the Vanderbilt Center for Stem Cell Biology for help with culturing mouse embryonic stem cells. The project was led by Vanderbilt faculty and benefited from the institution’s expertise in stem cell biology and chromatin regulation.

What were your top three findings?

We studied how certain genes in female cells turn off one of their X chromosomes, which is crucial for normal development. We found that these genes regulate each other in different ways depending on how active they are—sometimes they interfere with each other, and sometimes they modify their surroundings to stay in control. This discovery helps us understand how gene activity is fine-tuned in cells.

Our main findings were the following:

- Transcriptional interference regulates Xist only at high levels of nascent transcription. At lower levels, transcription of Xist and Tsix can occur simultaneously without interference.

- Histone modifications, specifically H3K36me3, deposited by Tsix regulate Xist expression. Medium levels of Tsix transcription correlate with the highest levels of H3K36me3, which inhibits Xist.

- Xist and Tsix do not physically bind to each other at significant levels. This finding disproves mechanisms involving RNA interference or transcript masking.

What do you hope will be achieved with the research results on the short term?

We hope others will apply the quantitative methodology to other antisense RNA pairs to uncover novel regulatory mechanisms. We also hope that this helps us develop an improved understanding of how transcriptional interference and chromatin modification work together in gene regulation, and that we can develop more precise models of Xist regulation that hopefully inform further studies on X-chromosome inactivation disorders.

What are your highest translational/clinical aspirations that might come as a result of this research?

Ultimately, we would love to see the development of therapeutic strategies targeting lncRNAs for diseases linked to X-chromosome inactivation, such as certain cancers and neurological disorders, and improved diagnostic tools to better understand mRNA and lncRNA misregulation for treatment recommendations. We also hope that the framework we developed can enhance antisense oligonucleotide therapies by helping researchers account for the different mechanisms of lncRNA regulation.

Where is this research taking you next?

We’re looking to expand this methodology to look at other lncRNA gene pairs and explore whether similar transcriptional mechanisms are at play. Within the context of X-chromosome inactivation, we will be investigating how chromatin modifications affect it over time using time-lapse microscopy and will explore the clinical potential of modulating lncRNA expression to treat diseases linked to Xist misregulation.

Is there anything else you would like to add?

I am very proud of the work we did, and I’m thankful for the efforts of first author Ben Kesler and second author John Adams.

We are also very thankful to Dr. Rudolf Jaenisch, Dr. Jeannie T. Lee, and Dr. Joost Gribnau for sharing reagents and cell lines, which were critical for conducting the study.

Go deeper

The paper “Transcriptional stochasticity reveals multiple mechanisms of long non-coding RNA regulation at the Xist – Tsix locus” was published in Nature Communications in May 2025.

The data and code described in this paper are publicly available online. Preprocessed data are available in the Zenodo Repository and image data are available at the BioImage Archive.

Funding

This research used funds from the National Institutes of Health, a Vanderbilt University School of Medicine Basic Sciences Dean’s Faculty Fellows award, and Vanderbilt startup funds.

SOMBS shared resources

This research made use of the Vanderbilt Center for Stem Cell Biology.