By Chuck Sanders

One of the benefits of going to Washington D.C. for work, such as NIH Study Section service, is that it provides an opportunity to visit the National Mall, whose spiritual center is the temple-like Lincoln Memorial. There, Lincoln sits deep in his chair and gazes out on the Republic, brooding on the past, present, and future—ever desirous of a more perfect Union. To his left is the Vietnam Memorial: inscribed with the names of the fallen and representing a still-not-completely healed gash. It is flanked by the moving Women in Vietnam Memorial and the Three Servicemen Statue. To Lincoln’s right is the haunting Korean War Memorial – a platoon of cold, wet, and lost-looking soldiers. What is their mission, and is there any chance it will be achieved? Still further to Lincoln’s right, Martin Luther King emerges from a giant slab of granite—immovable but unfinished. Will his vision be fully realized, or will it forever remain a dream? Great monuments not only venerate our heroes but also pose difficult questions.

Speaking further of historical cities and monuments, on February 4, I drove to Montgomery, Alabama, with my wife, Becky, and our youngest son, Adam. This day was the 110th birthday of Rosa Parks, whose unwillingness to move to the back of the bus sparked the 1955 – 1956 Montgomery bus boycott, one of the epic events of the U.S. Civil Rights movement. We visited the fascinating and beautiful Oakwood Cemetery, where we were surprised by a group of 75 Royal Air Force graves next to the tomb of musician Hank Williams. Apparently, the British sent many pilots to Montgomery during World War II for flight training at nearby U.S. Air Force bases. Who knew? The dates on the 75 tombstones were between 1941 and 1942, but all different. One can only wonder what conditions led to the sad loss of so many young men in separate training accidents. We also saw many graves from 1918 for persons of all ages, portending the visitation of the last big pandemic. But we did not travel to Montgomery for the graveyard. We went to see the new Legacy Museum and The National Memorial for Peace and Justice. And to be honest, while we mainly went to see the memorial, it was the museum that left the most profound impression.

The Legacy Museum combines art, an overwhelming collection of facts, and personal touches to document the persistent forces that have and continue to confront Black people in America, starting when they were first kidnapped in West Africa and hauled to Virginia. Early exhibits include dynamic swarm video plots that show the flux of enslaved people transported to the various major human markets in the New World as a function of the year from the 1500s to 1860. A second swarm video showed the eventual shift of the enslaved population from its focus around the coastal ports to the markets and cotton fields of the inland south. Montgomery hosted the largest human market in Alabama and was the clearing house from which this state’s enslaved population, numbering 430,000 by the mid-19th century, radiated. The next stop in the museum re-creates the holding cells of a human warehouse inhabited by life-sized holograms of men, women, and children who, when approached, tell you their story of suffering.

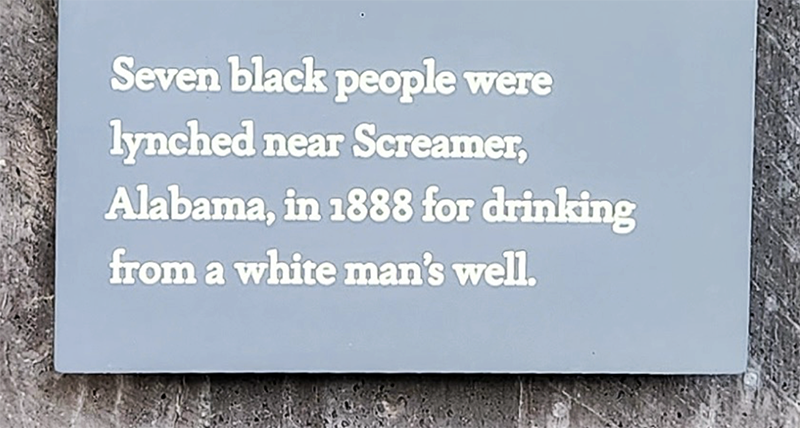

The era of slavery formally ended with the American Civil War. The Legacy Museum dedicates the next section to the systematic post-war oppression and terror inflicted on the newly-liberated Black community for scores of years, particularly in the south, with the most horrifying component being the practice of lynching. Lynchings, often supported by and even scheduled with the local authorities, often included torture and sometimes employed forms of murder far crueler than mere hanging.

Dedicated to the victims of lynchings, the huge National Memorial for Peace and Justice sits on a hillside a mile from the Legacy Museum, overlooking downtown Montgomery. The names and dates of death for the more than 4000 documented victims of lynchings are inscribed on huge hanging slabs of iron – one slab for each of the hundreds of U.S. counties in which at least one lynching is known to have taken place. I am very sorry to say that my beloved home, Davidson County, Tennessee, was not unrepresented at this memorial. The Legacy Museum features a display of hundreds of jars of dirt, each collected from the site of a documented lynching and makes the case that the terror of lynchings was a major contributor to the Great Migration of Black people from the mostly rural south to the northern cities during the first half of the 20th century.

The next section of the Legacy Museum recalled the brave work of the Civil Rights era but continued to the present, concluding with a sobering meditation on the systemic injustice and inequity that continues to plague American society. This is reflected not only by outrages such as the murders of Tyre Nichols, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and many others, but also by national and local policies and laws that are biased against Black people, resulting in higher incarceration rates and longer sentences than for white persons committing similar transgressions. Included is a simulated jailhouse visitation room where convicts await your visit on the other side of virtual Plexiglass screens, with whom you can engage by picking up the telephone. A young man told me of being sentenced to life in prison at 14 and having studied hard to earn his high school graduate equivalent degree but then being informed that he would be denied access to further education in jail because there was no point to it. A middle-aged woman told me of being raped by a correctional officer, getting pregnant, and having her beautiful baby taken away from her within 24 hours of birth, never to be seen again. There is a tragic symmetry of this display with exhibits early in the museum describing conditions under slavery.

The uplifting final stop in the Legacy Museum is its soaring hall of honor featuring pictures of leaders in the struggle for equality and justice. I was especially pleased to see Dr. Marie Maynard Daly’s lovely face peering down from high on the wall. Dr. Daly was the first Black woman to receive a Ph.D. in chemistry here in the United States and did truly pioneering work at the biology-chemistry interface, as recognized by the new Marie Maynard Daly award of the The Protein Society.

I recently learned from 23 and Me that I am 1% West African, with the coupling that resulted in this happenstance being estimated from the genetic analysis to have occurred in the 1600s. It seems unlikely that the forever-lost story behind this event is happy. In any case, the fact of the matter is that I am just an “old white guy” who has enjoyed the privilege that this identification affords him here in America. Yet, I am grateful to have had the chance to attend the Legacy Museum and visit the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which provides insight into 2023 America that embodies Faulkner’s maxim that “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” I hope what my family and I experienced there will make us less tolerant of the surging and unpatriotic notion that we should expunge acknowledgement of the cruel history of slavery and the continuing legacy of racism from our schools and other public discourse. Facts matter.

Acknowledgements

I thank Selene Colon, Bil Clemons, Shannan Cunniffe, Raluca Cadar, Jeanne Hardy, Heather Pinkett, Jamaine Davis, and Sheila Jaswal for helpful comments and edits. “Strange Fruit” is acknowledged as originally being the title of a difficult-to-listen-to Billie Holiday song. I also want to note that we found present-day Montgomery a welcoming and enjoyable place to visit.