Chuck Sanders, Vice Dean, Vanderbilt School of Medicine Basic Sciences

British author J.R.R. Tolkien had a lot to say about the creative process and I’d like to explore how his thoughts relate to the pursuit of cutting-edge scientific research. Tolkien’s The Silmarillion provides both the mythological underpinning of Middle Earth and the pre-history to The Lord of the Rings. A decisive event in this collection of tales occurs when the archetypical materials scientist, Fëanor, captures the light of the two sacred trees of Valinor, Telperion and Laurelin, in three synthetic jewels: the silmarils. When Morgoth and his walking-black-hole companion Ungoliant later kill the trees, the value of the silmarils as the surviving vessels of divine light becomes inestimable. When urged by the gods to share the silmarils to mend the damage wrought by Morgoth and Ungoliant, Fëanor declares, “For the lesser even as for the greater there is some deed that may be accomplished but once only; and in that deed their heart shall rest. It may be that I can unlock my jewels, but never again shall I make their like; and if I must break them, I shall break my heart, and shall be slain…”

Tolkien here sets a theme that turns up again in LOTR: the intriguing notion that not only can the creative process be draining, but that it sometimes involves an irretrievable investment of part of one’s very soul. Fëanor’s transfer of his essence to the silmarils presages the later transfer by Sauron of his own power, cunning, and malice into the One Ring. This soul-transfer eventually turned out to be a liability for Sauron. In the case of Fëanor, he proved to be tragically flawed. The silmarils were stolen by Morgoth. In attempting their recovery, Fëanor was killed by Gothmog, Lord of Balrogs, but not before betraying his own kin.

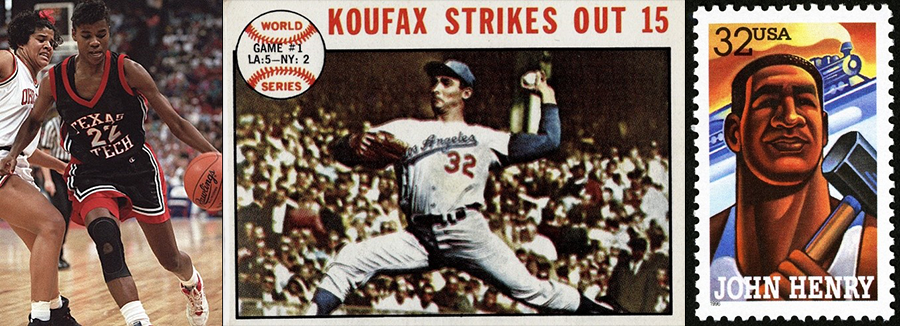

There are real world analogies to Tolkien’s concept of soul-transfer. Most folks are well-acquainted with the phrase “leaving it all on the court” (or field or pitch), referring to an astounding sports performance by an athlete, who is used up in the process. I am reminded of Cheryl Swoopes’ 47-point basketball rampage in Texas Tech University’s victory over Ohio State in the 1993 NCAA national championship game. Of course, Ms. Swoopes fully recovered from that game and went on to other legendary performances in the WNBA.

A tragic example is provided by Sandy Koufax, who from 1962 to 1966 may have been the most dominating left-handed pitcher in the history of major league baseball. In his final season at the age of 30, he won 27 games, allowing an average of less than 2 runs per game and striking out 320 batters. However, the tremendous mechanical stresses associated with the delivery of 100-mph fastballs was destroying his arm—he was in agony during his final two years, prompting retirement at the height of his power. Koufax really did leave it all on the field and never got it back.

One also recalls the legendary railroad worker, John Henry, who wielded two 10-pound hammers in a mountain-tunneling competition with a steam drilling machine, winning the match but dying of cardiac arrest in the moment of victory.

Artists also understand the personal investment of soul that accompanies the creative process. In the lyrics of “Lo and Beholden,” poet and musician Patti Smith describes the toll of making art: “For beauty and the naked truth, it will cost you!”

Returning to Middle Earth, long after the saga of the silmarils ended the Fellowship of the Ring set out to destroy Sauron’s lost ring before he could recover it and thereby fully consolidate his power. I invite you to consider the Fellowship as a group of lab scientists. There are three key principal investigators: Gandalf, Galadriel, Elrond, who commission the quest and have their own magic rings, with powers of encouragement, preservation, and memory-keeping.

The PIs recognize the One Ring as an arch-temptation that they dare not touch, leading them to set up a project with the specific aim of having their trainees destroy it. The project team includes a star postdoc, Aragorn, who also steers clear of the Ring, but who is strong enough to undertake a Zoom call with Sauron that unsettles the dark lord. The flawed postdoc Boromir yearns to be a PI but is not yet ready. Gimli and Legolas are more junior postdocs who originally viewed each other as rivals, but eventually form a deeply collaborative friendship that seems to shield them from ring-obsession. Finally, there are the graduate students, Frodo and Sam, and the undergrads, Merry and Pippin.

They are mostly happy to follow the guidance of the PIs, with additional mentoring by the postdocs. They were selected for the Fellowship precisely because they are NOT prone to putting heart and soul into things beyond friends, family, everyday comforts, and loyalty to commitments-made. Nevertheless, the most outstanding of these students, Frodo, is ultimately ensnared by the power of the Ring and is rescued only by a combination of friendship (Sam) and fate (Gollum). Even after the destruction of the Ring, Frodo forever carries a wound that cannot be healed in Middle Earth—he had become ensnared in the soul-investments of his mentors and their Enemy.

Indeed, by committing themselves to the plans of the PIs, all four student hobbits end up being caught up in a project where they face grave risks (e.g., Merry’s qualifying exam with the Witch King!) and are forced to surmount formidable challenges. When the PIs in The Lord of the Rings leave it all on the court, not only are they forever diminished (their rings lose their powers when the One Ring is destroyed), but the lives of the other members of the Fellowship are forever altered.

I suspect that most of us are aware of some of the costs involved when heart and soul are invested in scientific research. As in LOTR, these costs are paid both by those making the primary soul-investments (often PIs) and also by those caught up in their scientific vision (often trainees). How can these complicated commitments and relationships be managed so that everyone involved wins? An incident in the LOTR saga may offer some useful insight. Other than Sauron, the Lady Galadriel, Elf-Lord, is the only character in Tolken’s lore who plays important roles both in the early events of the Silmarillion and then, much later, in LOTR. Back in the day, she knew Fëanor personally.

When she meets the Fellowship of the Ring—the collective now caught up in her Ring-destruction project—she places herself into the mind of each fellow to assess how they are dealing with the challenges and stress of the quest. This maximizes her empathy and also enables her to prepare useful gifts for each fellow and to provide wise counsel to the group leaders. Notable among the gifts is “Galadriel’s phial” given to Frodo, which is strikingly silmaril-like. Her empathy, wise counsel, and gifts serve to bolster and equip the fellowship, enabling it to carry on in its difficult journey. This empathy worked both ways. Frodo’s disarming innocence and generosity helps Galadriel to finally make decisive life-choices she has long evaded, but needs to make. And her interactions with Gimli amuse and delight her in a way that she finds truly refreshing. This leads her to grant Gimli an unusual wish, one that she had denied to Fëanor thousands of years earlier.

Concluding on a scientific note, Galadriel’s meeting with the Fellowship reminds us that research projects are at their best not only when they tap into the skills and brilliance of the project team, but also when the team and its leaders are listening empathetically to each other and striving for collaborative outcomes where all participants share in both the trials and the glory.

Acknowledgements:

I thank Raluca Cadar and Stephen Doster for their edits. This article was also published in Under the Microscope, the newsletter of The Protein Society.