By Lorena Infante Lara

In 1951, Martha Fant, a schoolteacher in Clarksdale, Mississippi, was pregnant with her second child. Living in the Jim Crow South, she and her husband, Wendell Fant, had access to few health care resources that were readily available to white Americans. Thankfully, the city of Mound Bayou, Mississippi, and its Taborian Hospital were only 30 miles away.

Mound Bayou, founded in 1887 by formerly enslaved persons, was a safe haven and relative oasis for Black residents of the Mississippi Delta. A variety of Black-owned businesses thrived there, and Black people were able to safely vote at a time when trying to exercise this basic right of citizenship could lead to death.

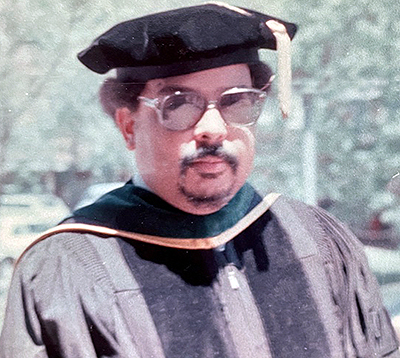

Taborian Hospital, which opened in 1942, was entirely staffed by Black health care workers. Its first chief surgeon, Dr. Theodore Roosevelt Mason Howard, became an important civil rights leader, working with and mentoring other young activists such as Medgar Evers and the Rev. Jesse Jackson. It was in this hub of civil rights activism that Dr. Michael Fant, Vanderbilt University’s first Black M.D./Ph.D. student and the first Black student in one of its biomedical sciences Ph.D. programs, was born.

A model to follow

Fant is now a professor emeritus of pediatrics at the University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine in Tampa, Florida, but his path was not a straight line connecting Mound Bayou to Tampa. It was, as it is for many Black Americans, a path that was winding and replete with hurdles and naysayers.

Fant’s parents, both graduates of Lane College, a historically Black college and university in Jackson, Tennessee, were strong advocates for education, their family, and the Black community. They constantly modeled a life based on a strong intrinsic sense of dignity, self-worth, and excellence that was not swayed by others’ opinions. A constant theme of his father’s counsel was to “stay true to yourself, do things the right way, and pay no attention to the noise.”

Wendell worked as a district executive for the Boy Scouts of America, recruiting, organizing, and training the volunteers who served as scout leaders. Because scouting was segregated at the time, he worked closely with many of the business, church, and educational leaders in the Black community to create the organizational structure that provided important developmental resources for Black boys and young Black men. Although so-called “Negro Boy Scouts” had fewer resources than white scouts, Wendell consistently set a high bar in terms of the recruitment and leadership metrics by which he and his coworkers, Black or white, were judged.

With Fant, the apple didn’t fall far from the tree.

When he was five years old, Fant’s family moved from Clarksdale to Memphis, Tennessee, where he grew up experiencing firsthand “colored-only” waiting rooms and water fountains and attending segregated schools where the textbooks were always hand-me-downs from neighboring white schools. However, “we were fortunate to have teachers who extended themselves to provide learning opportunities far beyond the restricted curricula and resources provided by the school district,” Fant said.

When he was a junior in high school, Fant became involved with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s youth movement in Memphis. He regularly participated in protests at the Memphis City Hall on behalf of sanitation workers who were striking for higher wages and better working conditions, a strike that led to Martin Luther King Jr.’s fateful visit to Memphis. Fant was there for the march King led and for King’s “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech, given the day before his assassination in April of 1968.

Ultimately, Fant overcame the institutionalized roadblocks, departing Memphis in 1969 for Cambridge, Massachusetts, to attend the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

A twist of fate

Determined to become a physician, Fant enrolled in MIT’s life sciences program, following a track in nutritional biochemistry and metabolism. There, he began to understand that nutritional intervention at the national and global levels was “more than just providing food and grain and throwing it at a community,” Fant said. “It’s infrastructure, economy, education, culture—it’s a whole host of things. The major determinants of nutritional status in a community depend on multiple variables specific to that community.”

As his studies progressed, Fant focused on the impact of malnutrition on human development. “I found myself growing angry at the fact that something as simple as a lack of nutrition during critical periods of postnatal development could permanently reduce a person’s genetic potential at birth,” Fant said, referring to the ways in which nutritional and environmental insults during critical developmental periods can permanently lead to the failure of a child to reach their full intellectual ability.

During his studies at MIT, Fant couldn’t help but see the impact of malnutrition in the context of the profound inequity between white communities and communities of color locally and between the developed world and nations of color globally.

“That the vast majority of cases where malnutrition was wiping out or stunting upward of 50 percent of a generation’s genetic potential were occurring were places where there were people of color pissed me off,” Fant said.

After MIT, Fant chose to continue his studies on malnutrition at the basic science level through the pursuit of a dual M.D./Ph.D. program. “When I looked around the country at programs, there were really only two or three options for me,” he said. Among the choices was Vanderbilt and its Department of Biochemistry, which was chaired by Dr. William Darby, a leader in the field of nutrition. “He had a cohort of faculty with him that promised to provide me with the perfect environment to pursue the interests I developed at MIT,” Fant said. The fact that Vanderbilt was closer to home helped seal his decision.

In 1972, Fant was admitted into Vanderbilt’s dual M.D./Ph.D. program and geared up to dive into nutritional biochemistry under Darby’s leadership. Yet fate—well, Darby—had other plans.

Before Fant started the program, Darby resigned as chair of biochemistry to serve as president of the Nutrition Foundation in New York. With his departure, the faculty Darby had assembled also began to leave, leaving Fant feeling like his primary reason for moving back to Tennessee had evaporated.

In the face of this uncertainty, Fant had to consider the options. “Do I stay? How do I make lemonade out of this?” Ultimately, he decided to stick it out.

Same goal, different focus

As Fant continued to assess the best way to pursue his long-term career plan, fate intervened again. Raymond Harbison, a young new faculty member with a primary appointment in pharmacology and a secondary in biochemistry, wanted to audit the anatomy class and was assigned to Fant’s dissection table. Harbison introduced himself and asked each of the four students about their interests and their plans. Fant described his interest in the developmental consequences of malnutrition and how his intended program had been “short-circuited” by Darby’s exit.

“Have you ever thought about the period of development before birth?” Harbison asked. He argued that far more consequential developmental events occurred before birth than after birth, that we knew essentially nothing about the period between conception and birth, and that we didn’t understand how the placenta—a unique organ that helps to direct traffic at the maternal-fetal interface—functioned.

“At that point,” Fant said, “My interest was piqued, and our conversations slowly pulled me into the world of placental biology. The opportunities to discover important new knowledge relevant to human development became very apparent and appealing.” Shortly thereafter, Fant joined Harbison’s lab as a graduate student in the Department of Biochemistry.

Breaking through the brick wall of homogeneity

Fant’s arrival at Vanderbilt occurred prior to its extensive efforts to foster diversity, equity, and inclusion in the M.D./Ph.D. program and across the institution that have since propelled it to the forefront of biomedical graduate training for minority students. Thus, he found very little diversity in the undergraduate school and even less within the medical and biomedical spaces.

In 1966, Dr. Levi Watkins Jr. became the first Black student to be admitted to the School of Medicine, and he remained the only one until his graduation in 1970—also a first. By the time Fant enrolled as a medical student in 1973, there were still only three other Black students at the School of Medicine; Fant and two other students in his class collectively became the fifth through the seventh to enroll.

“The optimism I had when I entered Vanderbilt was quickly tempered by the realities of day-to-day life as a student,” Fant said. “It was a bit disappointing, to say the least. I’d spent the last four years at MIT—surrounded by Harvard, Boston University, Northeastern University—being conditioned by a relatively more progressive academic environment compared to other parts of the country.” MIT had its own diversity challenges, but they continually engaged with students to address them.

Vanderbilt, it seemed to Fant, “was sociologically stuck in a 1950s time warp.” When the Black students as a group or Fant individually attempted to raise concerns or address issues related to student recruitment, support, or even the scholarly examinations of racial disparities in health outcomes, there was a palpable resistance by administrators and leadership to acknowledge the existence or significance of these issues.

“Vanderbilt’s mindset was, ‘we don’t have any diversity problems, there are no racial problems here, everything is fine as it is,’” Fant said. “Coming to Vanderbilt from MIT was, in many ways, a greater culture shock than going from Memphis to MIT.”

While the country had largely gotten used to the idea of the “Black kid” wanting to be a “doctor,” the expectation among many white people was that Black physicians would or should return to their communities and work in neighborhood clinics. Fant, who sought to become an academic physician and join the ranks of the faculty at a medical school, came to realize that many were not yet comfortable with a Black student having such aspirations.

“Why do you want to get a Ph.D.?” some members of the biochemistry faculty would ask. “You know how hard that’s going to be, right? Why don’t you just get the M.D. and then maybe, if you still want to do it later, you can come back to the Ph.D.?”

“Resistance, indifference, and efforts to dissuade and discourage were familiar forces I had to deal with. But I had seen it all before and understood it for what it was,” Fant said. “Moreover, my success at MIT armed me with the sense of calm and confidence I needed to move forward.”

Along the way, Fant was able to identify faculty members who provided a strong support network and served as a counterweight to the more negative forces at play. In addition to Harbison, his primary mentor, Fant became close friends with and was mentored by Dr. Robert Harrison, a Black basic scientist and a clinical endocrinologist who worked in the Department of Medicine, and the future Dr. Robert Taylor, one of the Black M.D. students in the year above him. Additionally, Fant received valuable mentoring and support from some faculty members, most notably from Dr. Ian Burr, Dr. Robert Cotton, and Dr. Mildred Stahlman in pediatrics, as well as Frank Chytil, David Ong, David Puett, and Robert Neal in biochemistry. Several of these relationships endured and grew into lifelong friendships.

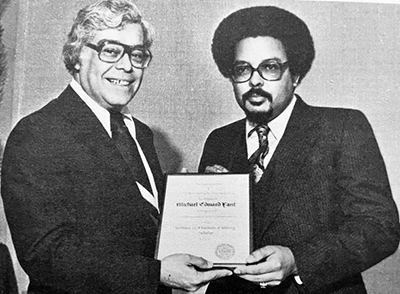

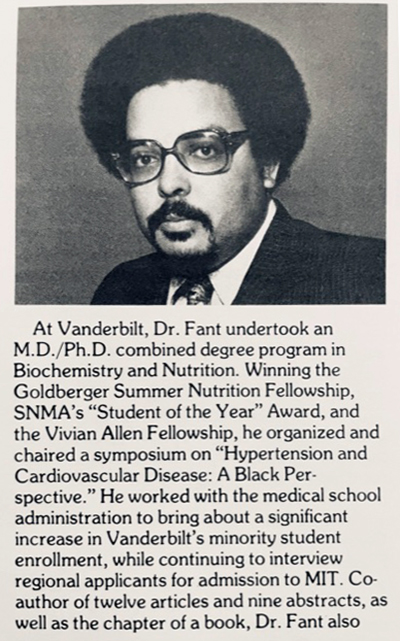

“Because of my own independence, self-confidence, and support network, I had a very productive tenure at Vanderbilt,” Fant said. By the time he graduated, Fant had presented his research at several national and international scientific conferences, published nine publications in peer-reviewed journals, and received two national honors from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

“It was an experience that I really wouldn’t trade because it created an unconventional yet critical pathway for me to do what I needed to do to become a successful physician-scientist.”

Of mice, genes, and future generations

Fant completed the M.D./Ph.D. program in 1980 and left Vanderbilt to climb the academic ladder. He went on to specialize in pediatrics at Boston Children’s Hospital and combined a neonatology fellowship at Harvard Medical School with a postdoc at MIT, training under Dr. Mary Ellen Avery and Dr. Hamish Munro, respectively.

After that, Fant embarked on his own independent academic career, which took him to the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, the John P. and Kathrine G. McGovern Medical School at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, and the University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine in Tampa. During his tenure at USF, he also served as the program director for its Neonatal-Perinatal Fellowship Program.

As a graduate student, Fant had switched his focus from postnatal development to prenatal development, with particular interest in the role of the placenta. After arriving at UT Southwestern, a large portion of his research explored the role of insulin-like growth factors, such as IGF1, in placental development and function.

Fant’s research interests later shifted to a gene called PLAC1 that was found to be strongly and primarily expressed in the placenta; he later demonstrated that it was also expressed throughout the embryo. To probe PLAC1’s role, Fant’s laboratory worked diligently to develop a knockout mouse model that did not express PLAC1 and demonstrated unequivocally that PLAC1 is essential for placental development as well as for brain development and function.

“Reaching a point in my career where I could say that we were able to contribute significant new knowledge to mammalian biology was immensely satisfying,” Fant said. “Isn’t that the point of it all?”

Throughout his academic career Fant has mentored a significant number of trainees at all levels of the educational pipeline in clinical medicine and basic research. “Sharing with young folks the excitement of taking care of sick newborns and of scientific inquiry relevant to that care while modeling the commitment and integrity required to pursue both properly was an immense privilege, and it was especially satisfying,” Fant said.

Fant was granted the emeritus title in 2019 and is in the process of completing several remaining manuscripts and reviews. As for what comes next, he expects to find other

roles where he can leverage his life experiences and expertise to contribute to the development of the next generation of physicians and scientists.

“I’ve retired from the job, but not the mission,” Fant said.