By Stephen Doster

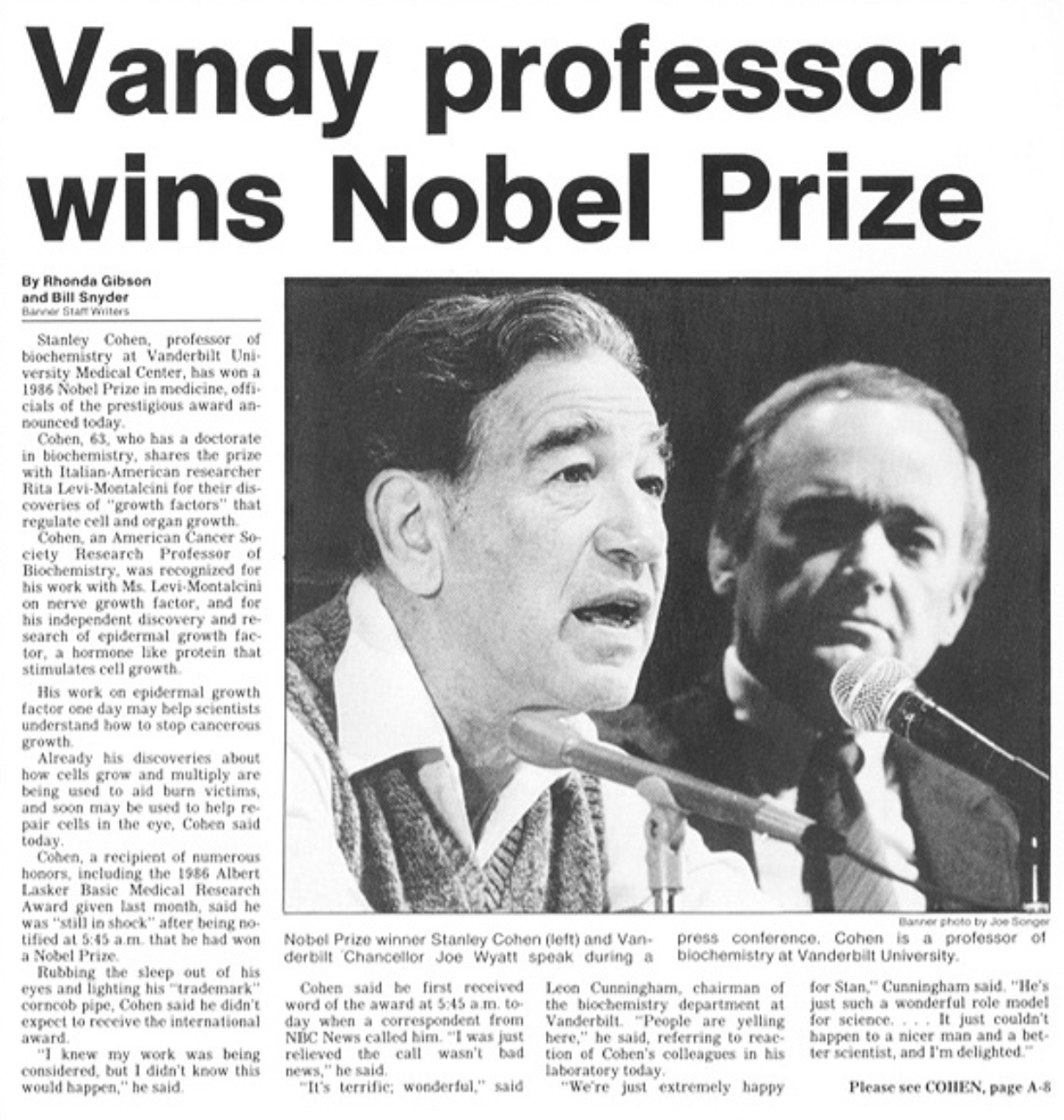

The phone rang in the wee hours of the morning. Fighting dread, Stanley Cohen, Distinguished Professor of Biochemistry Emeritus, picked up the phone. “For the first time in my life the middle-of-the-night call was good news,” he later said.

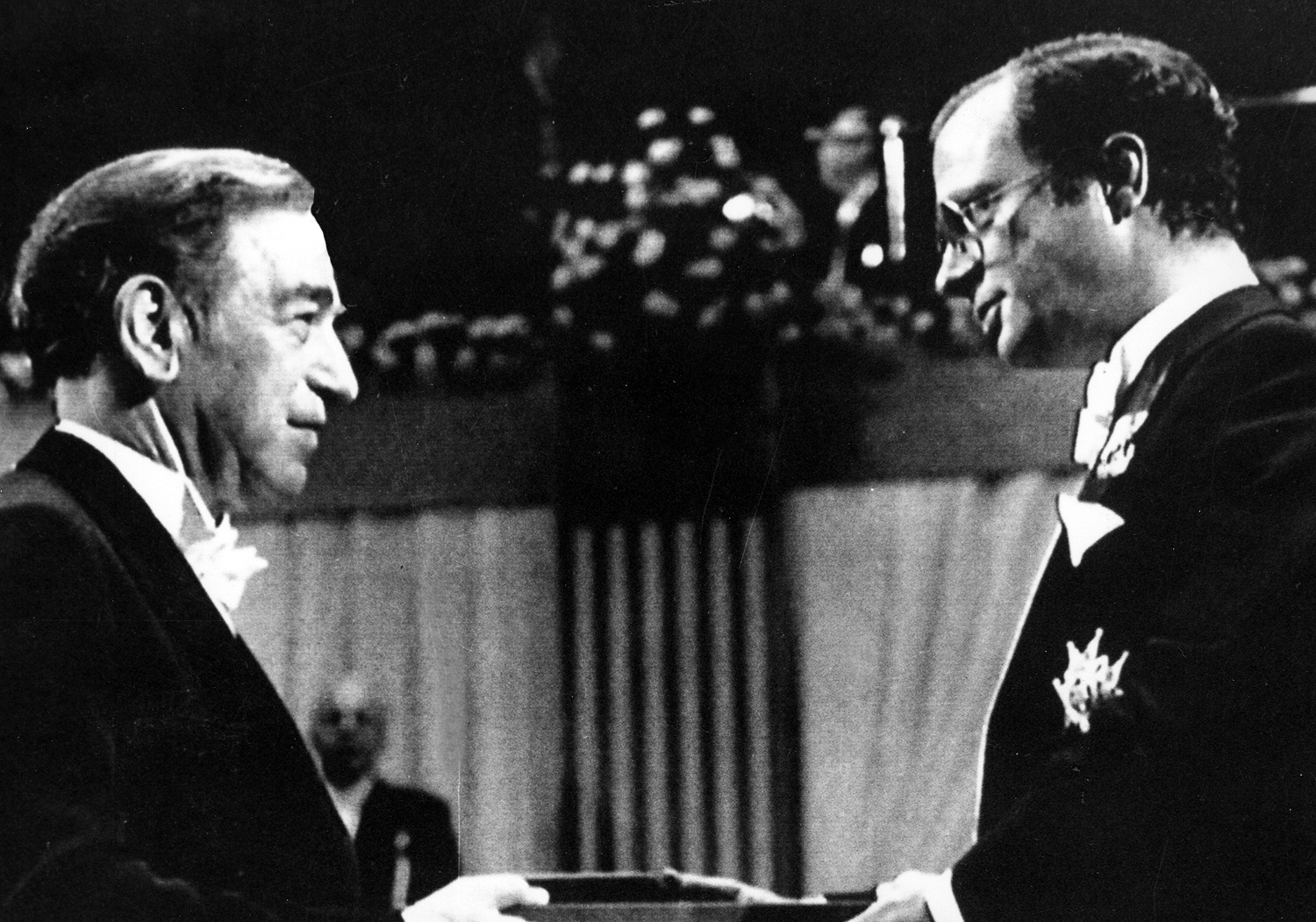

The call was to notify Cohen that he’d been awarded the 1986 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his discovery of epidermal growth factor, a protein produced in the body that influences the development of nerve and skin tissues by stimulating cell growth and differentiation. Cohen, who died in 2020, shared the Nobel Prize with Rita Levi-Montalcini, an Italian neurobiologist with whom he had collaborated in the 1950s during their time at Washington University in St. Louis.

“The discovery of EGF launched an entire field of research into growth factor signaling and had major impacts on human health,” Department of Biochemistry Chair David Cortez said.

Although cancer remains a complex and challenging disease, the knowledge gained from Cohen’s discovery has paved the way for transformative advancements that have extended lifespan, enhanced symptom management, improved treatment efficacy, and provided greater hope for patients and their families. From early detection and personalized therapies to improved supportive care and survivor- ship, cancer patient outcomes in 2023 are substantially better compared to outcomes 100 years ago.

“For example, there are more than 10 cancer drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration that target EGF receptors and many more that interfere with downstream signaling components,” Cortez said. “These drugs help tens of thousands of cancer patients each year.” Such targeted therapies, including EGF receptor inhibitors, have shown success in specific diseases such as breast, colorectal, head and neck, non-small cell lung, pancreatic, and thyroid cancers as well as squamous cell (skin) carcinoma.

Additionally, several biological processes, including immune system regulation, have been identified thanks to Cohen and Levi-Montalcini’s work. Ongoing clinical studies on the therapeutic properties of nerve growth factor, which they were attempting to isolate when they discovered EGF, focus on neurodegenerative diseases—such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease—traumatic brain injury, epithelial diseases and wound healing, and eye disorders such as corneal ulcers, glaucoma, retinitis pigmentosa, macular degeneration, and optic gliomas.

Recently, Vanderbilt researchers—led by Dr. Raymond Harris, professor of medicine and molecular physiology and biophysics, and Dr. Ming-Zhi Zhang, professor of medicine—discovered that activation of EGFR is essential for the development of kidney fibrosis, which could lead to the first effective treatment for this condition and may provide insight into the development of fibrosis in other organs.

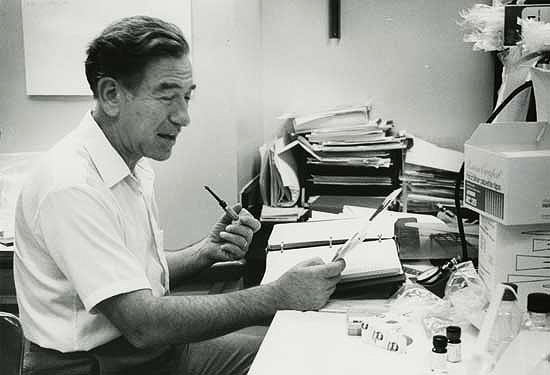

Being a Nobel laureate gave Cohen a platform to promote the need for basic research. “The road to medical discovery often begins as an unmarked trail,” he said to interviewer Vicki Brown in 1986. “We’re not always smart enough to know when the work is relevant. We must work on applying what we know but continue putting more money into finding out what we don’t. It’s not possible to think what will be the most important research 100 years from now.”

Or even 10 years from now.