By Aaron Conley

Established in 1925, the Department of Physiology—now Molecular Physiology and Biophysics—went beyond clinical training and cultivated robust and enduring research in a variety of disciplines, including diabetes research. Dr. Rollo Park, who became the department chair in 1952, was the first to prove that insulin could transport glucose into cells. Park recruited and trained dozens of students who themselves went on to impact the field. Tetsuro Kono, for example, discovered that glucose transporters cycled between the cytosol and cell membranes.

A pivotal transformation occurred in 1963 with the arrival of Dr. Earl Sutherland, a decorated former U.S. Army surgeon under Gen. George S. Patton. Sutherland’s lab delved into the role of cyclic AMP in hormone action, unraveling its intricate roles in cellular signaling pathways. Their discoveries laid the groundwork for many therapeutics, exemplified by the use of the hormone glucagon in insulin overdose cases, and earned Sutherland the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1971.

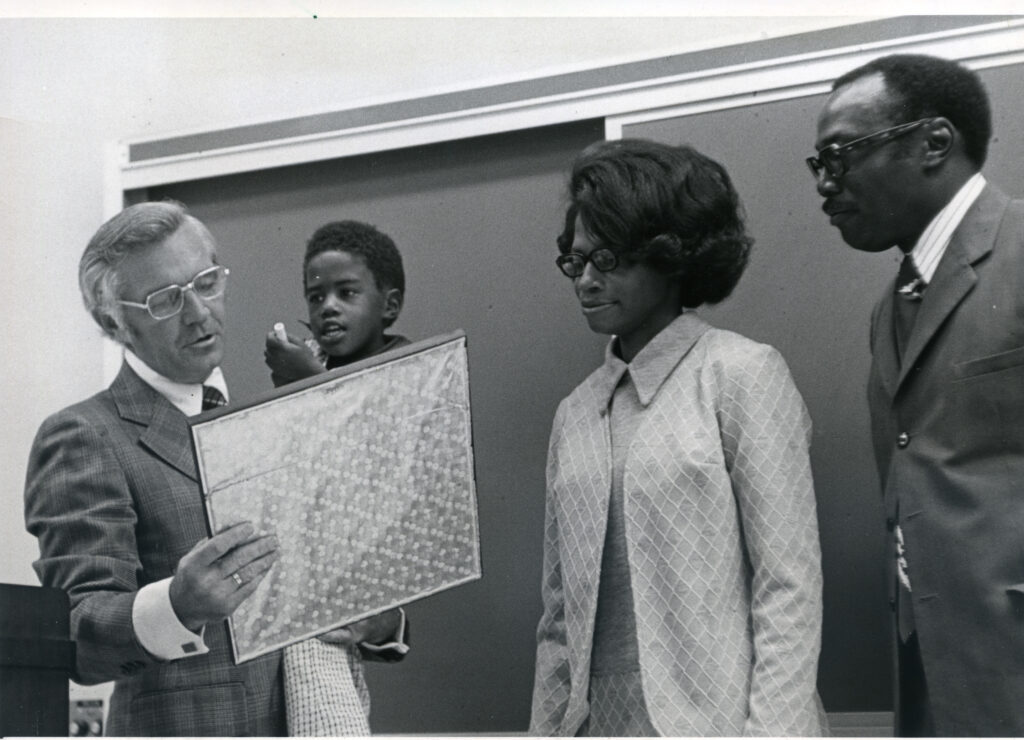

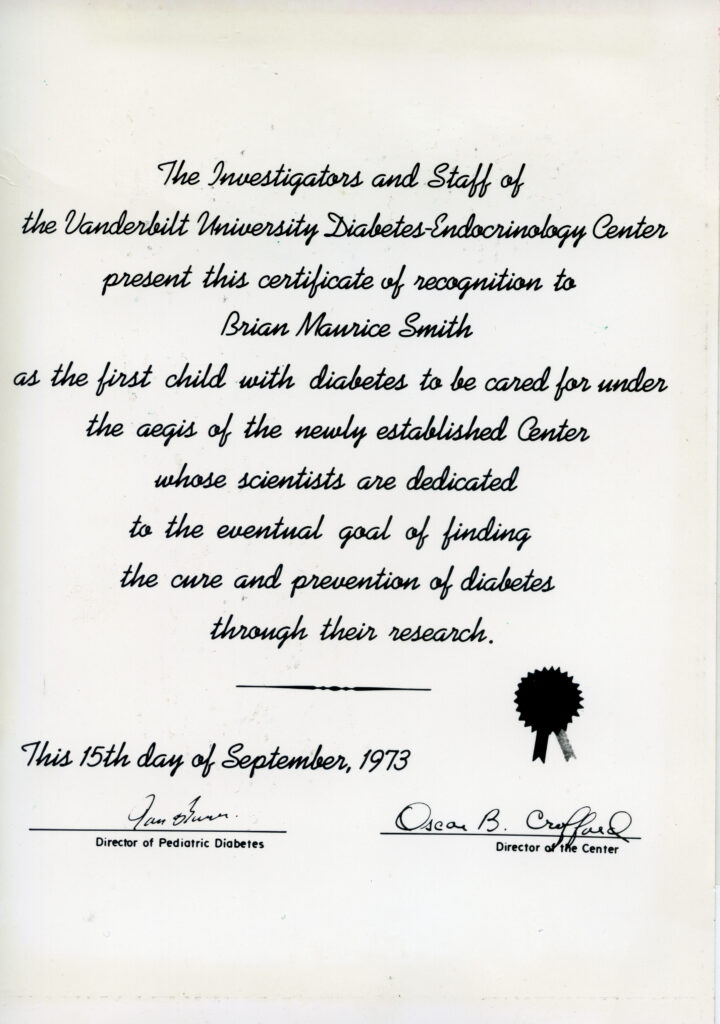

Dr. Oscar Crofford joined the physiology faculty in 1965 and focused on insulin’s effects on adipose tissue. This work led to a class of drugs that targets fat cells and helps control metabolism. Crofford chaired the National Commission on Diabetes, which made recommendations to the U.S. Congress and championed the National Diabetes Act of 1973. This act launched diabetes centers across the country, including the Vanderbilt Diabetes Center—the nation’s first. Crofford also chaired a groundbreaking, $165 million clinical trial that found that proper use of insulin lessened complications in diabetic patients.

A Sutherland postdoctoral fellow, Dr. John Exton, who died in 2023, played a vital role in studying gluconeogenesis and its hormonal control and went beyond cyclic AMP to understand calcium signaling in cells.

Exton nurtured a generation of scientists, including Alan Cherrington. Cherrington, who arrived at Vanderbilt in 1975 and is now a professor of molecular physiology and biophysics, solidified our understanding of glucagon as a hormone and showcased the different roles of epinephrine and norepinephrine versus glucagon in the responses to various challenges. Cherrington and his trainees created a one-of-a-kind animal model and partnered with pharmaceutical giants Eli Lily and Novo Nordisk to develop designer insulins. He was also involved in developing a newer class of drugs called GLP1 receptor agonists, which are now widely used to treat type 2 diabetes.

Dr. Daryl Granner, a clinician and researcher, was recruited to chair the department in 1984. He was one of the world’s first molecular biologists and changed the name of the department to the current “molecular physiology and biophysics” to showcase this new field. He uncovered the way in which insulin regulates genes important for glucose metabolism and directed the VDC for 16 years. The center, now renamed the Vanderbilt Diabetes Training and Research Center, is to this date one of the top diabetes centers in the nation.

Today, living with diabetes is managed through accurate blood sugar testing, controlled use of insulin, and myriad drugs, and treatments. These advances have been made possible through tireless research at Vanderbilt and across the globe.

“Diabetes research in the department has been preeminent for decades,” Cherrington said. “There have been many significant discoveries, some of which have been recognized with an array of awards and many of which have played a role in the development of new therapeutic agents. I doubt that there is another department of its kind in the world that has had, and continues to make, as much impact in diabetes research and its contribution to patient care.”