The “Two-body Problem” in academic medicine: Match 2020 edition

by Ayesha Muhammad (M2)

Whether in the midst of a pandemic, or during a 7-8 year-long MSTP, life happens, which might involve finding a long-term partner. For some of our graduates this year, finding their partners did not happen in the most logistically convenient way. This leads to the “two-body problem,” i.e. when two partners are trying to train or get a job in academia at the same time. This can be a major source of stress for many couples who meet during or before their training, due to the low rates of successful postdoc to professor transitions among PhDs. Thus, they have to navigate an additional barrier: how do both partners climb the academic ladder while staying together. Our M4s this year not only successfully completed this training, but also went through the Match process, all while navigating their relationships and cooperating with their significant others. They shared their insight into the two-body problem in academic medicine.

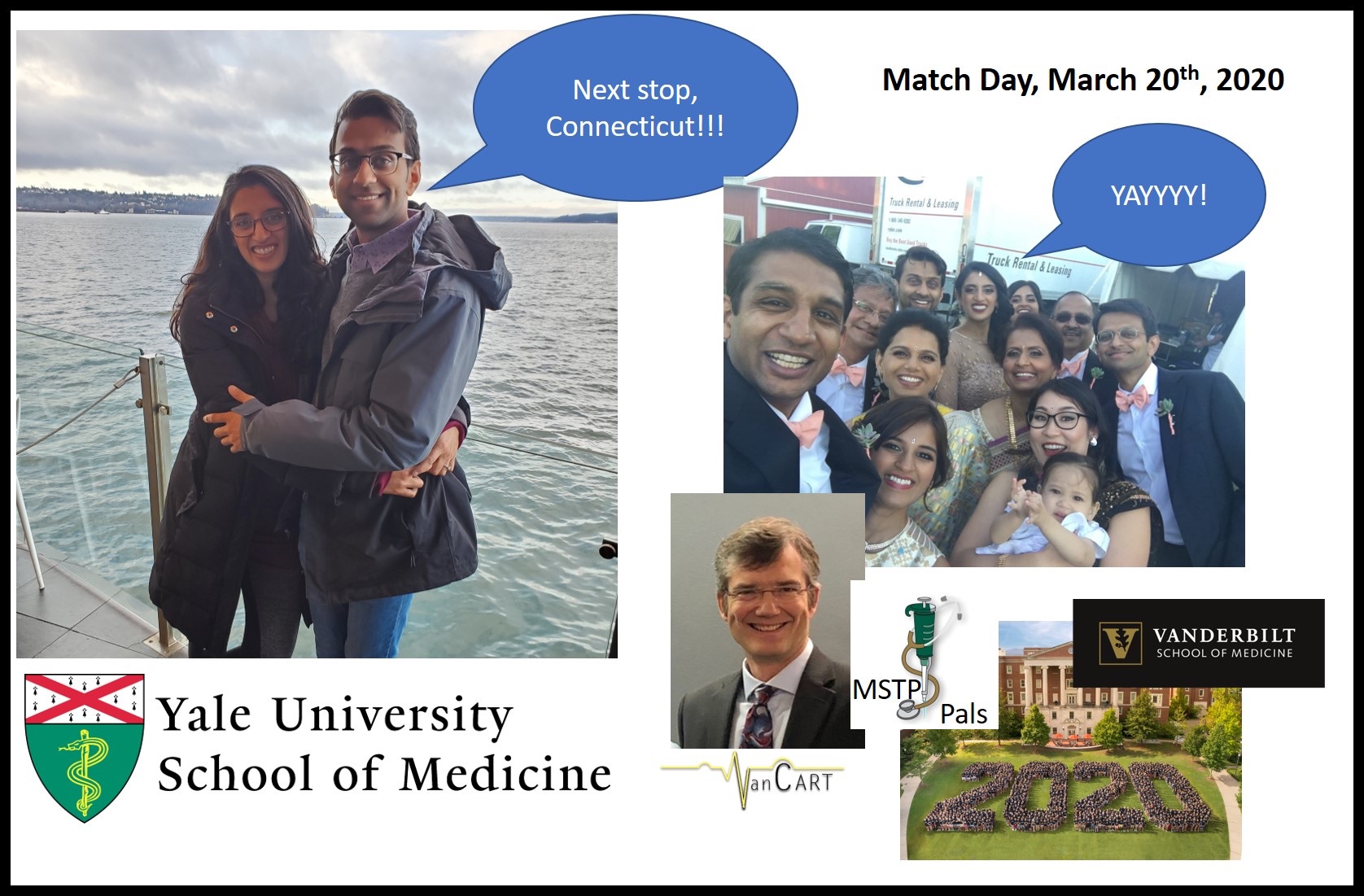

Shan Parikh, M4, who matched in Internal Medicine at Yale, has a partner who works in Veterinary Medicine and now lives in Nashville. When asked about navigating the two-body problem, Shan highlighted the difficulty of the issue and shared specific tips on rank list submission. “Happy family, happy life. Family commitments weigh on us more and more. These commitments should not feel like an obligation. If our family is happy, it makes it easier to focus on our aspirations at work and in our personal life. These are the prime years of our life and likely most formative years of our children’s lives.” He suggests that in the end you might have to compromise on something, while keeping in mind that there are many great institutions, and you’re going to be similarly successful in the top 10-20 programs. At the end of the day, “success is not possible without [your own happiness and contentment].”

Katherine Konvinse, M4 going to Stanford for Pediatrics, spent her entire time in Nashville navigating a long distance relationship/marriage with her husband, who is an engineer, across multiple states. She emphasized open communication about both personal and professional, short-term and long-term goals, over time, since “your goals will change over time. Make space to talk [and listen] about the differences in your ideologies and plans.” Katherine also took an unconventional path, as in she did not apply or interview broadly, nor did she rank all of the programs where she interviewed. “Professionally, all job opportunities for my husband are on the West Coast so I only applied to a limited number of schools on the West Coast.” She also interpreted the conventional match process advice of “whether you would rather train at that program or not be a doctor at all” differently. Most people want to put their hard work to obtain a medical degree to practice medicine, training somewhere is their top priority, so they rank all their programs. However, for her, top priorities were to live with her husband and to have a fulfilling career in discovery and research, resulting in a [relatively] shorter rank list.

M4, Nick Harris’s partner Kelly Harris, is a medical professional. They got married during his G2 and her M4 year, starting “the complicated pathway of being a dual-physician household without the benefit of being on the same timeline.” This past year, she was applying for fellowships in Pediatric Palliative Care as he navigated the residency match process. Having navigated through her residency process earlier, they had experience to guide them. Their tripartite recommendation to make sure they stayed together, while “both of [them] can pursue our career goals and maintain the personal life [they] desire without one bearing the brunt of the sacrifices:” 1) casting a wide net, 2) being transparent with everyone, and 3) leaning on mentors.

Nick and Kelly both applied to far more programs than the average candidate in their position. They also took all the interview opportunities presented to them over the course of 6 months. “At each interview, we both made our primary priority clear – to stay together – and we emphasized [both our professional] development beyond the immediate next step in training. We proactively asked for my interviews to be scheduled early to be as informed as possible when submitting Kelly’s rank list. Each of us individually and as a couple relied heavily on our clinical and research mentors, including some that went through a similar process with their partners. (Special shout-out to Dr. Dan Moore for making himself available for couples-advisory sessions). ” In the end, their hard work and thoughtfulness paid off: they both matched at their first-choice programs at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC). To their delight, they discovered that “[institutions viewed] their “two-body problem” as an opportunity, not a burden…”