This Month in Science and Medicine History: November 2024

by Leigh Ann Gardner (MSTP Senior Grants Manager)

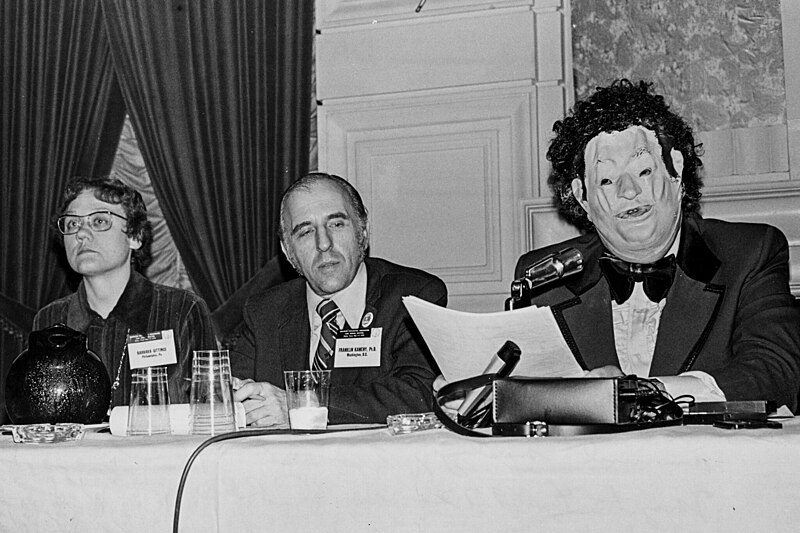

November 7: Born on November 7, 1937, in Winchester, Kentucky, John E. Fryer was a notable psychiatrist and advocate for LGBT equality thanks to his work to have homosexuality removed as a classified mental illness in the APA Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Fryer received his undergraduate degree from Transylvania University and received his medical degree from Vanderbilt University in 1962. He initially began a residency at the Menninger Foundation in Kansas, but later transferred to the University of Pennsylvania, where he faced discrimination due to his sexual orientation. He completed his residency at Norristown State Hospital. He joined the faculty at Temple University in 1967. Fryer is best known for his actions at the 1972 APA (American Psychiatric Association) convention, where he disguised himself as Dr. H. Anonymous. Sitting on a panel as Dr. Anonymous, he announced that he was homosexual, that many other psychiatrists had to hide their orientation, and that the stance of the APA towards treating homosexuality as a mental disorder was wrong. His speech is credited as being a factor in the APA removing homosexuality as a mental disorder from the DSM the following year. Dr. Fryer lived and worked in Philadelphia until his death in 2003. You can learn more about him and his fight for LGBT equality at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s online exhibit here or you can read a brief biography of him here.

November 7: Born on November 7, 1937, in Winchester, Kentucky, John E. Fryer was a notable psychiatrist and advocate for LGBT equality thanks to his work to have homosexuality removed as a classified mental illness in the APA Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Fryer received his undergraduate degree from Transylvania University and received his medical degree from Vanderbilt University in 1962. He initially began a residency at the Menninger Foundation in Kansas, but later transferred to the University of Pennsylvania, where he faced discrimination due to his sexual orientation. He completed his residency at Norristown State Hospital. He joined the faculty at Temple University in 1967. Fryer is best known for his actions at the 1972 APA (American Psychiatric Association) convention, where he disguised himself as Dr. H. Anonymous. Sitting on a panel as Dr. Anonymous, he announced that he was homosexual, that many other psychiatrists had to hide their orientation, and that the stance of the APA towards treating homosexuality as a mental disorder was wrong. His speech is credited as being a factor in the APA removing homosexuality as a mental disorder from the DSM the following year. Dr. Fryer lived and worked in Philadelphia until his death in 2003. You can learn more about him and his fight for LGBT equality at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s online exhibit here or you can read a brief biography of him here.

November 11: On November 11, 1938, Mary Mallon, the first publicly identified asymptomatic carrier of typhoid fever, died in New York. Born in Ireland in 1869, little of Mallon’s early life is known. She is believed to have immigrated to the United States in 1883 or 1884, where she worked as a cook. In 1906, while working as a cook in the home of wealthy banker, six people in the household contracted typhoid fever. The family hired George Sober to investigate how the illness had spread to the family, and Sober’s investigation led him to conclude that Mary was the carrier of typhoid fever, although she herself displayed no signs of illness. His investigation uncovered that household members in other families that she worked for in the past had contracted typhoid fever. Sober wanted to obtain samples from Mallon of her blood, urine, and feces, but she refused. Sober went to the New York Department of Health in 1907 and argued that she needed to be detained and tested for the safety of the public. She was forcibly taken to a hospital for testing and then quarantined at Riverside Hospital on North Brother Island for two years. In 1909, she unsuccessfully sued to be released; however, the following year, the public health commissioner allowed her release on the condition that she would not work as a cook. Mallon did not abide by the terms of her release, and returned to work as a cook, which did pay considerably more than domestic servant work. In 1915, she was arrested after it was discovered she was working under an assumed name as a cook at Sloane Maternity. During the three months she worked at the hospital, at least 25 people contracted typhoid fever, and 2 died. She was returned to quarantine at Riverside Hospital, where she remained for 26 years until her death. Her case sparked much public interest and debate, especially once other asymptomatic carriers were identified but were not quarantined or tested as often as she was. She was dubbed “Typhoid Mary” by the press, and by that name she is still often referred. You can learn more about her life, and the ethical issues surrounding her quarantine here and here. You can read selected newspaper articles about her life and her case dating from 1907-1915 here.

November 11: On November 11, 1938, Mary Mallon, the first publicly identified asymptomatic carrier of typhoid fever, died in New York. Born in Ireland in 1869, little of Mallon’s early life is known. She is believed to have immigrated to the United States in 1883 or 1884, where she worked as a cook. In 1906, while working as a cook in the home of wealthy banker, six people in the household contracted typhoid fever. The family hired George Sober to investigate how the illness had spread to the family, and Sober’s investigation led him to conclude that Mary was the carrier of typhoid fever, although she herself displayed no signs of illness. His investigation uncovered that household members in other families that she worked for in the past had contracted typhoid fever. Sober wanted to obtain samples from Mallon of her blood, urine, and feces, but she refused. Sober went to the New York Department of Health in 1907 and argued that she needed to be detained and tested for the safety of the public. She was forcibly taken to a hospital for testing and then quarantined at Riverside Hospital on North Brother Island for two years. In 1909, she unsuccessfully sued to be released; however, the following year, the public health commissioner allowed her release on the condition that she would not work as a cook. Mallon did not abide by the terms of her release, and returned to work as a cook, which did pay considerably more than domestic servant work. In 1915, she was arrested after it was discovered she was working under an assumed name as a cook at Sloane Maternity. During the three months she worked at the hospital, at least 25 people contracted typhoid fever, and 2 died. She was returned to quarantine at Riverside Hospital, where she remained for 26 years until her death. Her case sparked much public interest and debate, especially once other asymptomatic carriers were identified but were not quarantined or tested as often as she was. She was dubbed “Typhoid Mary” by the press, and by that name she is still often referred. You can learn more about her life, and the ethical issues surrounding her quarantine here and here. You can read selected newspaper articles about her life and her case dating from 1907-1915 here.

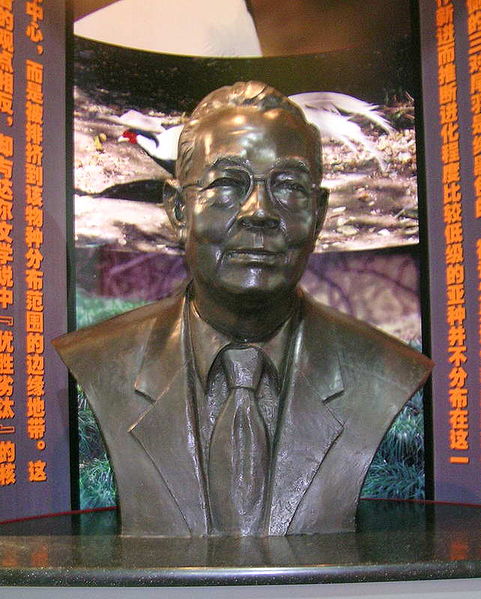

November 18: Renowned ornithologist Tso-Hsin Cheng (Zuoxin Zheng) was born on November 18, 1906, in Fujian Province, China. After obtaining his PhD from the University of Michigan in 1930, Cheng returned to China to study ornithology. Prior to the 1920s, ornithological studies in China had been done by Western naturalists, and often did not describe avian fauna or how birds were distributed. After his return to China, Cheng started fieldwork on wild birds and their characteristics, and in 1947, he published the “Checklist of Chinese Birds,” which listed 1,087 species and 912 subspecies of birds in China. He and colleagues also identified 16 new bird subspecies as well as studying the evolution of pheasants, laughing thrushes, and other birds. He disagreed with China’s campaign to eradicate sparrows (as well as mice, flies, and mosquitoes), which led to him being deemed “reactionary” and at one point led to the confiscation of all his belongings. However, Cheng continued his research, and in 1989 he received the First Prize of Science and Technology Progress Award of the Chinese Academy of Science. He was the founder of the China Ornithological Society and co-founder of the China Zoological Society. Cheng died in 1998, and you can read more about his life here. You can learn more about his difficulties during the Cultural Revolution here.

November 18: Renowned ornithologist Tso-Hsin Cheng (Zuoxin Zheng) was born on November 18, 1906, in Fujian Province, China. After obtaining his PhD from the University of Michigan in 1930, Cheng returned to China to study ornithology. Prior to the 1920s, ornithological studies in China had been done by Western naturalists, and often did not describe avian fauna or how birds were distributed. After his return to China, Cheng started fieldwork on wild birds and their characteristics, and in 1947, he published the “Checklist of Chinese Birds,” which listed 1,087 species and 912 subspecies of birds in China. He and colleagues also identified 16 new bird subspecies as well as studying the evolution of pheasants, laughing thrushes, and other birds. He disagreed with China’s campaign to eradicate sparrows (as well as mice, flies, and mosquitoes), which led to him being deemed “reactionary” and at one point led to the confiscation of all his belongings. However, Cheng continued his research, and in 1989 he received the First Prize of Science and Technology Progress Award of the Chinese Academy of Science. He was the founder of the China Ornithological Society and co-founder of the China Zoological Society. Cheng died in 1998, and you can read more about his life here. You can learn more about his difficulties during the Cultural Revolution here.

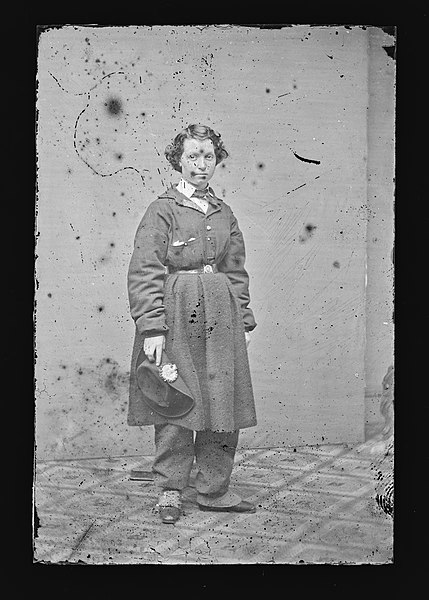

November 26: Born on November 26, 1832, Mary Edwards Walker was the first female surgeon in the US Army, and the only woman to receive a Medal of Honor. Born to abolitionists, her parents encouraged Walker to think freely and to receive an education. Walker worked a few years as a teacher to earn money to attend medical school, and she received her medical degree from Syracuse Medical College in 1855. When the Civil War began in 1861, Walker tried to obtain a job as a surgeon in the US Army but was denied. She worked as a volunteer and nurse, and in 1862, moved to Virginia so that she could treat injured soldiers. In 1863, the US Army allowed her to begin practicing as a surgeon, and she was the first female U.S. Army Surgeon, serving with the Army of the Cumberland, although she was not officially commissioned by the US Army. In 1864, she was captured by Confederates and imprisoned as a spy. Released as part of a prisoner exchange in 1864, she continued her work as a doctor in the US Army. In 1865, President Andrew Johnson awarded her a Medal of Honor due to her service. However, since she was never officially commissioned as a surgeon, she was not allowed a pension. After the Civil War, she continued to practice medicine and advocated for women’s rights and dress reform. Preferring to dress in men’s clothing, she was often ostracized and ignored by others in the women’s suffrage movement. In 1916, her Medal of Honor was taken away from her after the government reviewed her eligibility. She refused to return the medal and continued wearing it until her death in 1919 at the age of 86. It was restored to her in 1977 by President Carter. You can learn more about her life here and here.

November 26: Born on November 26, 1832, Mary Edwards Walker was the first female surgeon in the US Army, and the only woman to receive a Medal of Honor. Born to abolitionists, her parents encouraged Walker to think freely and to receive an education. Walker worked a few years as a teacher to earn money to attend medical school, and she received her medical degree from Syracuse Medical College in 1855. When the Civil War began in 1861, Walker tried to obtain a job as a surgeon in the US Army but was denied. She worked as a volunteer and nurse, and in 1862, moved to Virginia so that she could treat injured soldiers. In 1863, the US Army allowed her to begin practicing as a surgeon, and she was the first female U.S. Army Surgeon, serving with the Army of the Cumberland, although she was not officially commissioned by the US Army. In 1864, she was captured by Confederates and imprisoned as a spy. Released as part of a prisoner exchange in 1864, she continued her work as a doctor in the US Army. In 1865, President Andrew Johnson awarded her a Medal of Honor due to her service. However, since she was never officially commissioned as a surgeon, she was not allowed a pension. After the Civil War, she continued to practice medicine and advocated for women’s rights and dress reform. Preferring to dress in men’s clothing, she was often ostracized and ignored by others in the women’s suffrage movement. In 1916, her Medal of Honor was taken away from her after the government reviewed her eligibility. She refused to return the medal and continued wearing it until her death in 1919 at the age of 86. It was restored to her in 1977 by President Carter. You can learn more about her life here and here.

Please acknowledge the Vanderbilt University MSTP Program if you share this information.