This Week in Science and Medicine History – February 2025

by Leigh Ann Gardner (MSTP Senior Grants Manager)

In February, we will recognize contributions to science and medicine made by African Americans. You can learn more about Black History Month here.

Week 1 (February 8): America’s first female African American doctor, Rebecca Lee Crumpler, was born on February 8, 1831, in Delaware. Crumpler developed an early interest in caring for the sick while being raised in Pennsylvania by her aunt, who cared for the sick in her community. Beginning in 1855, Crumpler worked as a nurse, and in 1860, she was accepted into the New England Female Medical College. She graduated in 1864, the first formally trained African American woman physician. Crumpler initially practiced medicine in Boston, but she moved her practice to Richmond, Virginia following the Civil War, stating it would be, “a proper field for real missionary work, and one that would present ample opportunities to become acquainted with the diseases of women and children.” She focused on treating women and children among the formerly enslaved. She returned to Boston in the late 1860s, and in 1883, she published A Book of Medical Discourses, which provides guidance on maternal and child health as well as relating her experiences as a doctor. Crumpler died in 1895 and is buried in Boston. You can learn more about her life here, and you can access A Book of Medical Discourses here.

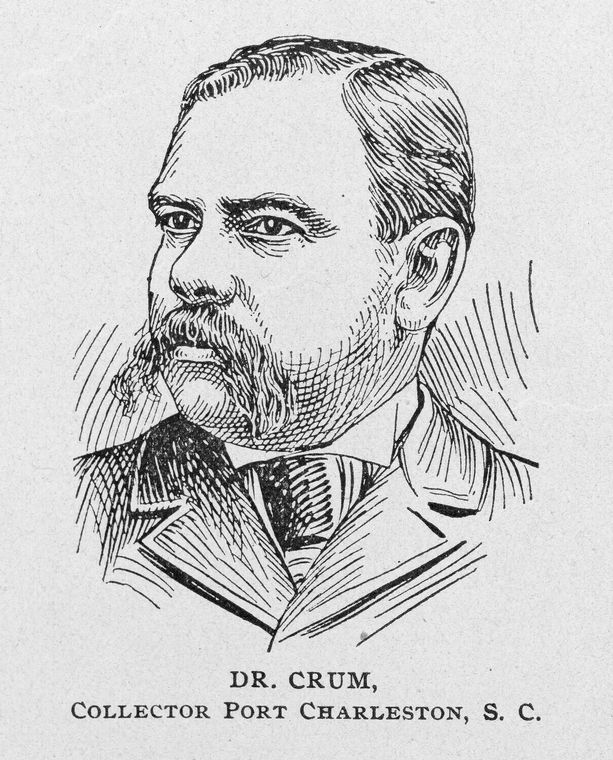

Week 2 (February 9): Physician and diplomat William Demosthenes Crum (also known as William Demos Crum) was born in Charleston, South Carolina, on February 9, 1859. Raised in South Carolina as the youngest of seven children, he received a medical degree from Howard University in 1881 and then returned to Charleston. He worked for the McClennan Hospital and Training School for Nurses and was also known for studying tuberculosis. Crum became involved in politics, acting as chair of the Charleston County Republican Party and attending national party conventions as a delegate. In 1902, President Theodore Rosevelt nominated Crum as the collector of customs for the port of Charleston, which resulted in widespread opposition to the nomination. Crum was not confirmed in the position until 1905. In 1909, he was appointed as minister to Liberia. Crum died in 1912, and you can read more about him here.

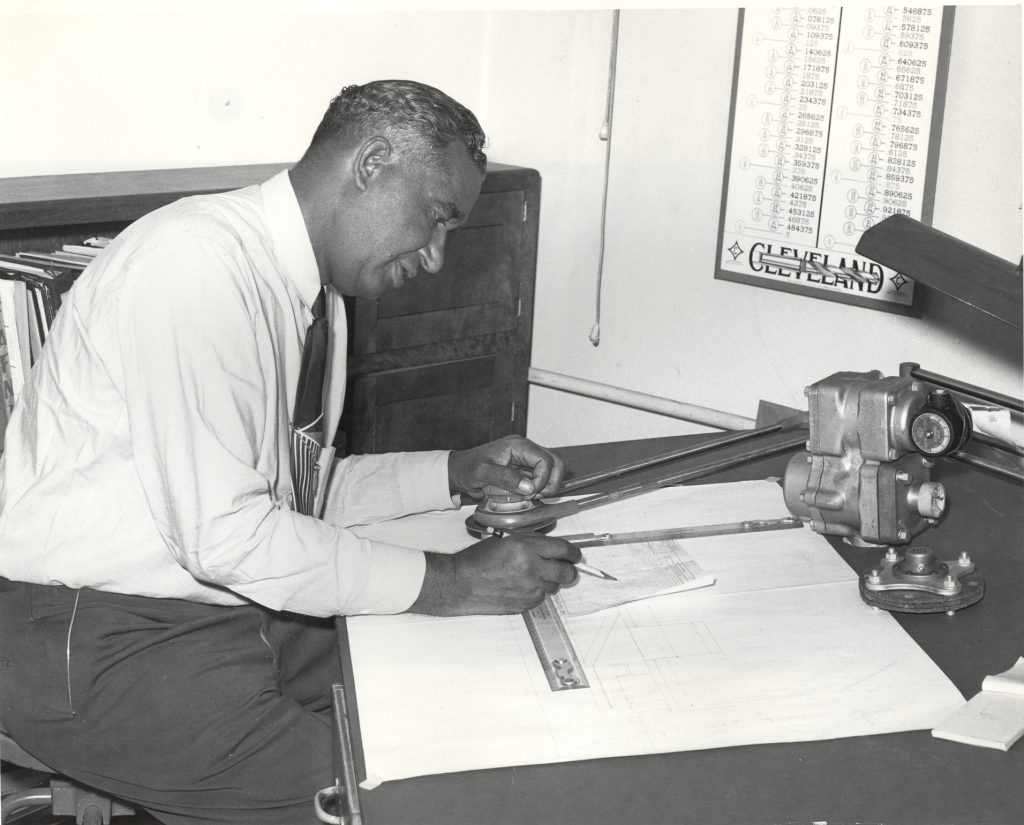

Week 3 (February 21): Engineer and inventor Frederick McKinley Jones, an innovator of mobile refrigeration and a notable African American inventor, died on February 21, 1961. Born in Cincinnati in 1893, he was raised by a priest in Kentucky from the age of eight. At eleven, Jones left school and returned to Cincinnati, eventually working as a mechanic. A talented mechanic, he received his engineering license by the age of twenty. Following service in WWI, he switched to electronics and invented a device that combined sound with motion picture. In the late 1930s, Jones designed a portable air-cooling device for trucks; he then adapted the design to fit trains and boats. Other inventions he was responsible for include a portable x-ray machine, an early snowmobile, and a soundtrack synchronizer. You can learn more about his life here.

Week 4 (February 28): On February 28, 2022, Hawaiian governor David Ige pronounced the day “Alice Augusta Ball Day,” in honor of a pioneering chemist whose contributions to the treatment of Hansen’s Disease were overlooked for decades. Alice Augusta Ball was born in Seattle on July 24, 1892, and she moved to Hawaii with her family in 1902. After receiving two undergraduate degrees in chemistry and pharmacy from the University of Washington, she enrolled at the College of Hawaii to pursue a master’s degree in chemistry. Ball became the first woman and the first African American to obtain a master’s degree in chemistry from the College of Hawaii. During her time there, she studied chaulmoogra oil, which was the only treatment for Hansen’s disease at that time. She created an injectable form of the oil which was more effective in the treatment of Hansen’s disease. Ball died in 1916 at the age of 24, and her work was largely forgotten by scientists. In the 1970s, some professors discovered Ball’s research records and began working to have her achievements recognized. You can learn more about Ball here and here.

Please acknowledge the Vanderbilt University MSTP Program if you share this information.