There are certain watershed moments that can change the trajectory of scientific discovery. One of those moments was the creation of AlphaFold, an AI system developed by Google DeepMind that predicts a protein’s 3D structure from its amino acid sequence, a more streamlined and accurate process compared to the slower and more error-prone methods of old. The AlphaFold database now provides open access to over 200 million protein structure predictions to help accelerate scientific research.

Started in June 2025, a new collaborative science project called diffUSE involving Vanderbilt University, Cornell University, and the University of California, San Francisco, could be the next watershed moment. The $5 million, three-year project led by the Astera Institute will advance our understanding of protein motion. Using diffuse scattering, an overlooked signal measured by X-ray crystallography, the project will determine how protein dynamics are characterized, leading to a new paradigm in dynamic structural biology.

“The AlphaFold breakthrough changed structural biology. It enabled us to take a sequence, predict a static structure, and make it available to everyone,” said Stephanie Wankowicz, assistant professor of molecular physiology and biophysics and a lead contributor to diffUSE. “The downside to AlphaFold is that it only captures a single, static structure of the protein. We need new ways to obtain information beyond just a static structure, where you’re able to get the dynamics or motion of the protein.” Wankowicz hopes that the results from diffUSE will also help answer a variety of questions, such as how those dynamics change when there is a ligand bound or when you have a mutation, how mutations cause disease, how one drug versus another could change the dynamics of the protein, and more. These scnearios all impact how a protein interacts with all of its partners in the cell and the way we treat and think about disease.

One of the goals of the diffUSE project is to see a drug company using this technique to design drugs within the next 10 years. “We want to democratize this enough that a clinical research organization can use it to be able to help with drug discovery projects,” Wankowicz said.

“Stephanie hit the nail on the head: Still-life pictures are not enough, we need the movies,” said Walter Chazin, Chancellor’s Professor of Medicine and professor in the departments of biochemistry and chemistry. Chazin is a leading expert in the experimental characterization of protein structural dynamics in solution. “Traditional structures are static snapshots of intrinsically dynamic polymeric molecules. These static structures are not sufficient to explain biology because all biological processes require molecular motions that take anywhere from femto-seconds to minutes. New methods are needed to incorporate dynamics into the interpretation of structures, switching from a static snapshot to a structural dynamics framework.”

Wankowicz was a natural fit for the diffUSE project. She has been a vocal advocate for open science, which ensures that algorithms are open source, data sets are open, and publications are available to all. She helped lead the charge in getting AlphaFold3 to be made open source and has been involved in encoding and infrastructure developments for the Protein Data Bank, which provides researchers with free access to 3D biostructure information.

Wankowicz is a core faculty member in the Vanderbilt Center for Applied Artificial Intelligence in Protein Dynamics. The center is led by Hassane Mchaourab, who holds the Louise B. McGavock Chair in Molecular Physiology and Biophysics and focuses on illuminating the principles that govern protein dynamics.

“Predicting, modeling, and designing protein dynamics is the next frontier in protein science. Decoding the time dimension of protein structures will have a transformative impact in multiple disciplines, from deciphering the mechanism of disease-linked mutations and the design and fine-tuning of drugs to the design of new proteins for specific applications in the clinic and industry,” Mchaourab said. During her graduate studies, Wankowicz discovered that proteins often modulate their dynamics upon ligand binding by becoming more dynamic in areas of the protein away from the binding site, which enables them to bind to their ligand tightly. “Dr. Wankowicz already made a lasting impact on the field during her graduate studies. This prestigious investment in diffUSE validates the approach she developed and will increase its adoptability and application.”

Diffuse scattering

Diffuse scattering is an untapped source of information that exists in X-ray crystallography, a mainstay structural biology technique, and it can enhance our understanding of protein dynamics. Knowledge of protein dynamics is essential for comprehending how proteins interact with other molecules and carry out their biological roles.

Thanks to computational and hardware infrastructure advances, diffuse scattering of a handful of proteins is now being analyzed. “There are a handful of labs in the world that work on it,” Wankowicz said. “The diffUSE project aims to democratize diffuse scattering by building accessible physical infrastructure, software, and downstream tools so that any lab can analyze protein motion in their system and uncover new biological insights from diffuse scattering.”

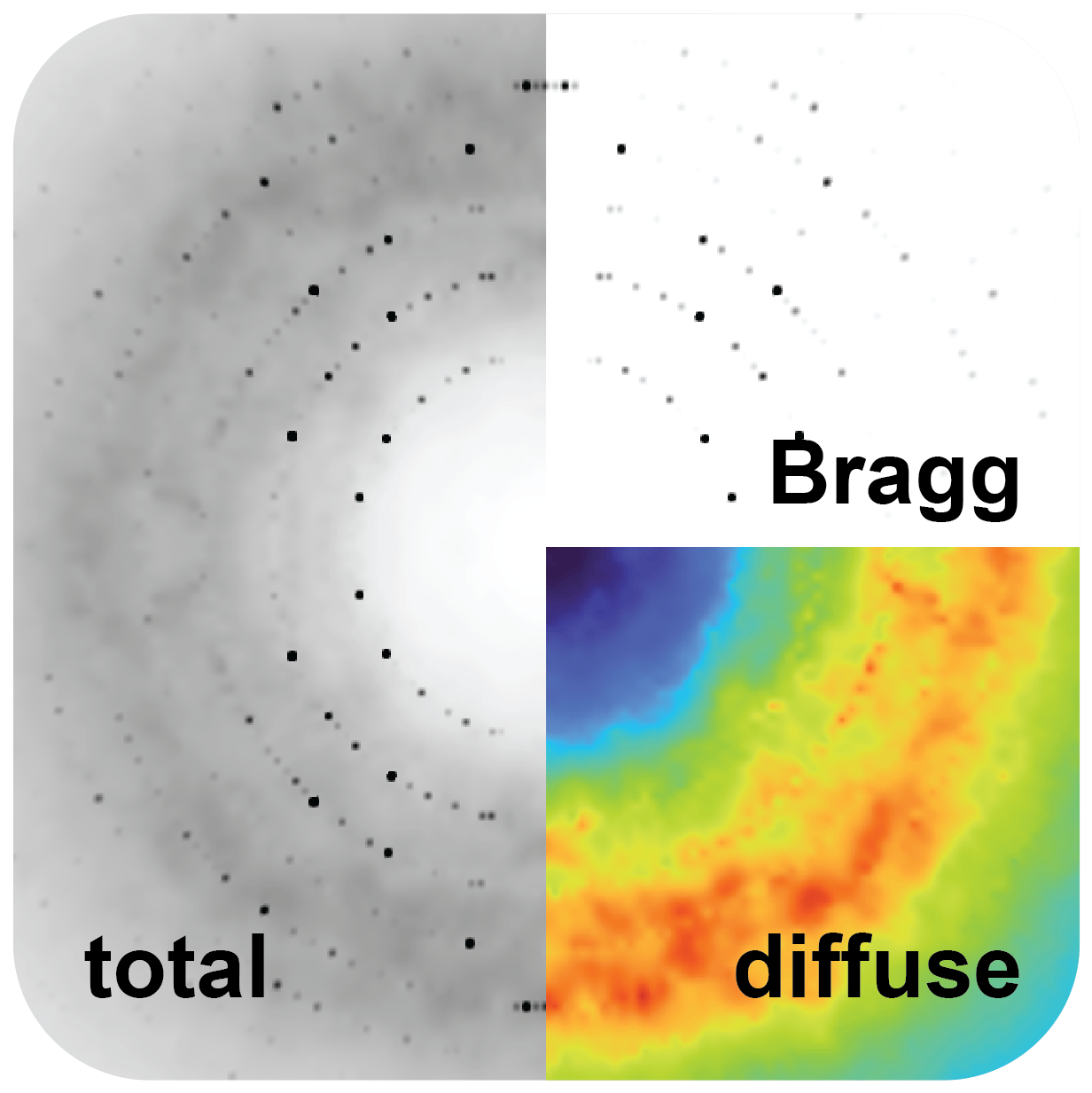

Typically, when you shine an X-ray beam at protein crystals, what we get back are these peaks called ‘Bragg peaks,’ and that is the repeating unit that happens. It’s basically indicating that ‘atom one’ is repeating in all these crystals. However, they’re not perfect crystals. Because proteins move, there are imperfections in them. What that causes is diffuse scattering, and it looks like clouds around very bright peaks.

These clouds contain information about how the proteins move within the crystals, and, importantly, how these movements are correlated, which is essential for understanding how enzymes work or how proteins bind to ligands.

Project milestones

Wankowicz and her colleagues will initially target a subset of proteins that crystallize well and then expand to others. “Our immediate goal is to target 15 different proteins of diverse size and function to learn about their differences and build the methodologies that are needed to do this on a lot of different proteins,” Wankowicz said.

The first major diffUSE project milestone, which the team plans to meet within the first 18 months, is determining whether they can collect data on five different proteins with no ligand bound and with ligands bound and whether those differences can be discerned in the modeling. The second milestone is developing computer modeling infrastructure that can work on a given protein but that can also integrate ligand and water molecules. “This is really important, as all of those individual pieces actually add up to the signal that you see,” Wankowicz said. Without models that explicitly account for all of those components, she said, “we’re never going to be able to get a forward model to predict the motions from the diffuse scattering data.”

Open protein dynamics database

The diffUSE project will be fully open source: All data, algorithms, and publications will be freely accessible to the public so others can build on them and make new discoveries. A major focus, which Wankowicz’s lab excels at, will be to build the infrastructure that makes such breakthroughs possible, inspired by how the Protein Data Bank underpinned AlphaFold. The team aims to extend the PDB with new modalities and robust data encodings, storing data in clear ways that both people and computers can understand.

Today, only about 80 percent of the data behind many protein models areexplained, but the diffUSE team is creating better algorithms to push that closer to 100 percent. By updating databases accordingly, researchers can readily apply these advances to analyze protein behavior and dynamics.

“Doing critical methods development openlygets me really excited about this project, not to mention the structural biology we’ll hopefully be able to discover and improve,” Wankowicz said. “Building tools and building software is an important part of biology, but sometimes it’s difficult to get financial support. Projects like diffUSE are typically funded by federal sources, so I’m happy to be supported by the Astera Institute.”

If AlphaFold has taught us what proteins look like, diffUSE may reveal how they move—transforming overlooked diffuse signals into concrete insights and ushering in the next watershed moment for open, data-driven discoveries.