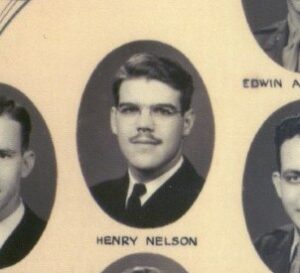

A life leading back home: Reflections from Dr. Henry Nelson (MD ’45)

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine alumnus, Dr. Henry Nelson, turned 99 on Jan. 16, 2022. Nelson died shortly after this interview sharing his reflections on a life in medicine. This story is dedicated to his memory.

By: Lexie Little

The year was 1949. Kathryn Wolff Nelson sat next to the crib holding her newborn baby in her room at Vanderbilt University Hospital. Physicians, medical students, and nursing students shuffled around to see the woman who had caused such a commotion.

“Is that the lady who requested her baby stay in the room with her?” one asked. “I heard she did it with her firstborn at Yale, but they’ve never allowed that here.”

To that point at Vanderbilt, no mother had ever been allowed to keep her child in the room with her postpartum. But Nelson, a top graduate and Founders Medalist of Vanderbilt’s nursing program, would come out on top again, this time with a little help from her surgeon father-in-law, Dr. Oscar G. Nelson, who advocated for child to remain with mother.

Through all the hubbub, Nelson’s thoughts remained with her husband Henry, then 7,404 miles away in Taizhou, China, where she once also lived. When communist forces moved south in 1948, the United States Consulate issued a warning for women and children to flee the country. That was December. This was January. And Henry, a Vanderbilt University School of Medicine graduate, would find his way back home after reviving a mission hospital.

All roads led home, to Vanderbilt.

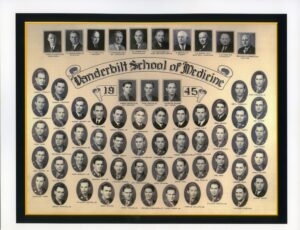

Dr. Henry Sperry Nelson graduated from Vanderbilt University School of Medicine at age 22 in 1945. Until his death at age 99, he returned regularly to watch the Commodore basketball team face off against Southeastern Conference foes. His father played basketball and coached for five years on the early Vanderbilt squads before staying on as a medical student and physician, so naturally, Nelson remained a fan. But Nelson’s affinity for Vanderbilt University ran much deeper than sports.

Traipsing around Vanderbilt’s campus at age 15, young Henry looked up at the gothic-style brick buildings, every outline of which he knew intimately. His father had been educated at Vanderbilt (1915 graduate) after a patron in Mobile, Alabama, sponsored his education following an academic competition. A precocious student, Henry finished middle and high school in five years and then decided he would follow in his father’s footsteps, completing a three-year pre-medical undergraduate education before entering medical school. No stranger to accelerated education, Nelson found foreign circumstances hastening his progress.

In December 1941, the United States faced the grim reality of World War II when Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor. The world would need doctors amid global carnage. One month later, Nelson received his acceptance to Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. His senior year at Vanderbilt dualled as his freshman, or M1, year of medical school, and he readied himself for a life of service.

Soon, the Commodores resembled commodores. Third-year students walked around campus not in white coats but in the uniforms of active-duty midshipmen like those in Annapolis, Maryland. Nelson enlisted in the Navy, too young for the draft set at age 21.

He and his classmates studied and rotated around the clock without academic breaks because of the war effort. The youngest member of his class, Nelson waited to serve his purpose on a global stage, whatever the mission. That mission eventually came, not one ordered by the military, but a literal missionary calling to China.

“There was just a very short period [between the war and communist occupation], and I think the Lord was just working to prepare me to be able to go at that time,” Nelson said. “The interesting thing is we were first assigned to a mission post called Jiaxing, but the hospital there was not yet ready to open and there was an older doctor who had been there before the war who came and was in the process of trying to build furniture and everything and get the hospital started. Shortly after we got to China, there was a mission meeting, and word came that Dr. Robert Price had been preparing to come back to reopen his hospital at Taizhou. He had a heart attack and died, and I was asked to take over his hospital.”

Nelson had a unique connection to Robert Black Price, an internist from Mississippi. Price graduated from Vanderbilt with an MD in 1906, nine years before Nelson’s father. Price started the Sarah Walkup Hospital in Taizhou in 1917, where he worked until 1941. The hospital, named for the mother of Belk department store founder William Henry Belk, had been funded by the Belk family. W.H. Belk retained an interest in medicine thanks to his brother and business partner, physician Dr. John Belk.

The war interrupted the hospital’s progress until Nelson arrived at age 25 in 1948.

“[Price] had been there under the Japanese occupation and was there when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. At that time, it made him an enemy alien. So, the Japanese interred him and repatriated him in a prisoner’s swap.” Nelson said. “We were able to, with the help of some of the older missionaries that had been there, gather together some of the staff: head nurse, pharmacist, several of the nurses, the hospital maintenance man, and we were able to get a laboratory technician that had been at a neighboring mission, so we had the central people to help me start the hospital. It’s amazing.”

Nelson’s career to that point proved equally amazing. As a third-year medical student, Nelson treated one of the first Vanderbilt patients to receive penicillin. Limited by the need for its use in the armed forces, Vanderbilt received restricted supplies for research purposes. Nelson also studied tropical diseases in his medical school public health course. That knowledge, combined with medical innovation, led to his pioneering work in the Congo.

“After I left China, I went to the Congo. I spent 30 years off and on in Congo. We often began using medicines there that were released in Europe before they were released for use in the United States. Tylenol, for instance,” Nelson said. “We used Tylenol for a couple of years before it was released in the United States. We used it especially in pediatric wards for reducing fever, but it was under a different name. It was not called Tylenol; it was using the European name.”

Medical innovations and discoveries in the mid-20th century revolutionized the great progress that colored Nelson’s career in treating hues of yellow fever, gangrene, and the red inflammation of leprosy.

Working in China, a patient disfigured by severe sores arrived for care. Remembering lessons from a VUSM public health professor, Nelson thought to himself, “This must be leprosy.” He quickly consulted with the hospital laboratory technician who knew how to take smears for testing. The results: positive. With the mission board’s help, Nelson acquired new sulfonamide drugs, the first effective leprosy treatment, from Hong Kong. He would see nearly 80 patients with the disease while in China. But work didn’t stop there.

In the Congo, Nelson served two isolation sites for leprosy patients, historically referenced as colonies. He made his way through two villages, working with more than 100 leprosy patients as tensions escalated under Belgian colonial rule. With the battle for independence looming in 1960, patients fled.

“We were right in a conflict zone where two different tribes were going back and forth in civil warfare,” Nelson’s daughter Elizabeth “Bizza” Britton said. “We had to leave [and return to Tennessee].”

Bizza, as she’s known to friends and family, stands as one of the few Nelson family members without a degree from Vanderbilt University. Nevertheless, the Louisiana nurse practitioner cheers for the black and gold even against her own alma maters like the University of Tennessee, where her mother taught graduate nursing in the 1980s.

No fewer than 10 Nelsons graduated from Vanderbilt, including four generations of surgeons.

“My father and grandfather got their medical degrees at Vanderbilt, but my brother and my nephew did their undergraduate at Vanderbilt and their medical training at the University of Tennessee in Memphis,” Bizza said. “[My brother Henry Sperry Nelson, Jr.] did some trauma surgery and vascular surgery at UT Medical Center. Now his son John, who graduated with an undergraduate degree from Vandy and medical school in Memphis, is now at the hospital there.”

The Nelson family maintains a Vanderbilt scholarship for pre-medical students started by and named for patriarch O.G. Nelson (Henry’s father) as a way to honor the generous donors whose financial contributions helped them to achieve their goals. Bizza remembers her grandfather, known as “Doc,” recounting the story of how the scholarship gift he received put their family on the road to education, to Vanderbilt. That sort of generosity touched the second generation when the president of Salem College encouraged Bizza’s mother, Katie, to attend Vanderbilt’s BSN program and helped her obtain scholarship money. Katie Nelson would later earn a PhD in International Education from Peabody College and train native Chinese instructors to start BSN programs in their home country.

Over the years, Henry Nelson opened letter after letter from pre-medical students thanking him for the family’s generosity. Paying it forward remains important to the Nelson family, especially now, in memory of Henry, the physician who saw many pandemic diseases not unlike that which the current generation faces.

As one of the first Tennessee residents to receive a COVID-19 vaccination, Nelson hoped the next generation of health care workers and physicians would use lessons from the past to inform the present.

“I’ve seen smallpox, HIV, a lot of tuberculosis, and I had a case in China that I think was bubonic plague. You name it, I’ve seen it,” Nelson said. “In Congo, I had a case of yellow fever. So, I’ve seen almost all the major diseases. In fact, smallpox, we had one of the last smallpox outbreaks in the Congo before the World Health Organization declared smallpox eradicated with the worldwide vaccination program.

“I’ve seen public health mandates in the past for measles and for polio. Why people refuse to or have gotten the idea that something’s wrong about vaccination is just really a sad turn of events, really. That’s how smallpox was eradicated, for instance. That’s how polio was eradicated from the States…I remember being at Vanderbilt at a time when there were entire wards of people on iron lungs with polio. You don’t see any of that, those iron lungs, anywhere now.”

But beyond practice, Nelson’s life and global work stood as reminders that medicine is first and foremost a commitment to people.

“Yes, he did mission work, but even here when they were in the United States, I can remember while I was in high school that Daddy was going out to a lot of the rural Appalachian clinics up in the mountains and helping to provide services and doing clinics in areas that needed extra help,” Bizza said. “There’s need everywhere in the world. I think his example to any medical student or nursing student would be that it’s not the highest paying job that gives you the most reward.”

And it starts at home. At Vanderbilt.