Kloosterman, McNew win Levi Watkins, Jr. Student Awards for diversity efforts

M4 Nicole Kloosterman and MD/PhD graduate student Kelsey McNew recently received recognition for their commitments to advancing equity, diversity, and inclusion at VUSM

by Lexie Little

In 1970, Levi Watkins, Jr., MD, became the first African American to graduate from Vanderbilt University School of Medicine (VUSM). From the moment he matriculated in 1966 until the end of his illustrious career, Watkins championed opportunities for underrepresented minorities and diverse populations in the sciences. To honor his legacy, Vanderbilt University grants annual awards to at least one faculty member, one graduate student, and one medical student associated with VUSM.

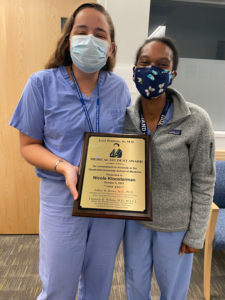

Last month, Vanderbilt honored fourth-year medical student Nicole Kloosterman and MD/PhD graduate student Kelsey McNew with the Levi Watkins, Jr. Student Awards for their outstanding service to advancing equity, diversity, and inclusion in the community.

Kloosterman advances Latino health

Kloosterman, nominated by classmate Alex Brito, immediately began her work as a champion for underrepresented future practitioners and patients in the Nashville community. As a first-year student, she served as the first-year representative of the Latino Medical Students Association, after which she transitioned to co-president, a position she has held ever since. Recently, she has served as the Director of Interpreter Services and Acute Care Coordinator for Shade Tree Clinic, where nearly 50% of all 300 patients are non-English speaking, in addition to work on the racial equity task force established in light of the social justice movement in 2020. An avid advocate for Hispanic and Latino patients, Kloosterman developed a medical Spanish curriculum at the School of Medicine to equip future physicians as culturally competent caregivers.

Kloosterman, nominated by classmate Alex Brito, immediately began her work as a champion for underrepresented future practitioners and patients in the Nashville community. As a first-year student, she served as the first-year representative of the Latino Medical Students Association, after which she transitioned to co-president, a position she has held ever since. Recently, she has served as the Director of Interpreter Services and Acute Care Coordinator for Shade Tree Clinic, where nearly 50% of all 300 patients are non-English speaking, in addition to work on the racial equity task force established in light of the social justice movement in 2020. An avid advocate for Hispanic and Latino patients, Kloosterman developed a medical Spanish curriculum at the School of Medicine to equip future physicians as culturally competent caregivers.

“Nicole is able to balance each of these avenues in addition to pursuing a challenging career as a future ENT,” Brito said in her nomination. “Her advocacy, particularly for Spanish-speaking patients, has had an enormous impact on care for underrepresented minorities in Nashville.”

Though widely published in health equity, Kloosterman said the award came as quite a surprise. In reflecting on her work in health equity at Vanderbilt, she credited others with the growth and continued aspirations set forth in equity, diversity, and inclusion at the School of Medicine.

Kloosterman feels the award remains more of a team win than just a single recognition, but she also feels a lot of pride in her accomplishment.

“This is something I have been passionate about for a long time,” she said. “Health equity is what first got me interested in medicine during my time in undergrad. I think of those earlier days in my training and the goals that I had, most of which revolved around incorporating public health practice into my medical career. This moment has served as a very meaningful time of reflection for me. The best part about these projects is that they are all a team sport. The skills and the knowledge I have gained through my various experiences working with diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives at VUSM, along with the people I’ve gotten to meet and the support through administration, through my friends, through staff have made various projects and ideas come to life. That’s the most exciting part about this award; you share it with people who have supported you along the way.”

Kloosterman credits her mentors like Dr. Adriana Bialostozky (pediatrics) and Dr. Kimberly Vinson, Associate Dean for Diversity Affairs at VUSM, for her development. Vinson presented the awards.

“I’m applying into ENT this year, a field that has huge potential for crucial health equity work and is a topic that has continued to evolve in this field particularly in the last couple of years,” Kloosterman said. “Dean Vinson, in her role at the medical school and as a practicing laryngologist, was really the first person to reassure me that continuing to do diversity, equity, and inclusion work while also pursuing a career in this surgical subspecialty was possible. She gave me permission to feel confident about navigating both realms and has allowed to me to seek mentors who have a similar mindset.”

“Without having her as a role model, someone who actively portrays those priorities through her own career, I think it would be really hard for me to visualize myself being able to pursue those two passions.”

Kloosterman likewise credited Bialostozky, with whom she has worked to develop the medical Spanish curriculum.

“I met Dr. B during my first year, working with her once a week to complete my continuity clinic. She is not only someone who is absolutely adored by her patients but someone who continues to navigate our health care system, trying to find ways to improve outcomes for Latino populations. She has been an incredible mentor since. Entering medical school, to practice medicine with someone who spoke my native language and interacted with patients who were like the people I had grown up around made me feel like I belonged early on,” she said.

With visibility in the examples of her mentors, Kloosterman set out to continue the mission of building an inclusive and equitable environment for both students and the patients they will one day serve. She said working with people so deeply passionate about their own communities bred accountability in her, too, pushing her to execute ideas. With the help of administration, she and her colleagues have taken measures to address needs meaningful and relevant to today’s cultural and health climates, currently working on establishing a certificate in Medical Spanish and Latino Health.

She hopes to see that curriculum continue to develop as national conversations within this rapidly increasing population brings Latino health to the forefront. She hopes, too, that VUSM continues its efforts to recruit and develop support systems for underrepresented minorities in medicine.

“Continuing to prioritize a diverse student body breeds diverse thoughts and ideas. By fostering support through mentorship and promoting the development of skills that will serve students far beyond their time in medical school inherently helps build more equitable systems and future providers. Vanderbilt has been an incredible place to train and develop some of these skills as there are faculty and administration who continue to push for new ideas and ways that the program can continue to grow,” she said, then turning her attention to what students themselves can do to continue creating a more equitable system.

“Students can first start by evaluating their experiences in the hospitals and within their own communities. Gaining a deeper understanding of people’s experiences and how they vary is a great starting point. From there, identifying why and how these differences exist and developing skills to bridge gaps in care is the next step. The great thing about striving for health equity is that there is something for everyone- all aspects of a patient’s care are affected in some way by a system that is inequitable, and while daunting, this allows everyone to play a role making change based on their own individual interests and priorities.”

McNew seeks support for LGBTQIA+ community

Like Kloosterman, graduate student Kelsey McNew maintains that passion remains at the core of setting out to enact change.

Like Kloosterman, graduate student Kelsey McNew maintains that passion remains at the core of setting out to enact change.

“I encourage students to think about what matters to them, think about what gaps they see in the physician workforce, and try to fill those gaps,” McNew said. “I think Vanderbilt is really good about supporting those ideas.”

Early on in her studies, McNew noticed little visibility for LGBTQIA+ students in the Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP), in which students earn both a PhD and MD. Since, she has worked to educate classmates and the community more broadly about queer health from the perspectives of patients and practitioners through PDx lectures in addition to involvement in MSTP recruitment.

Her classmate, Daniel Sack, nominated her for the award.

“Kelsey has tirelessly worked to create a more inclusive culture within the MSTP program,” Sack said. “Kelsey not only makes current students feel like valuable members of the community but meets with every applicant interested in learning about LGBTQIA+ resources at Vanderbilt.”

To her, the Levi Watkins, Jr. Award represents the acknowledgement of all of the different ways that people – patients and providers – are diverse. With a commitment to creating a health care workforce that matches all the identities patients bring to clinical settings across the country, she strives to establish consistent practice of allowing individuals to bring their whole selves to health care settings.

“It’s so powerful that our identity helps us to fill gaps in medicine. We are unique individuals with this training, finding ways to channel our identities into taking care of patients. We’re thinking about ways to bring our full selves to patient care,” she said. “That visibility really matters to people. Think about how comforting it must be for someone without the knowledge to navigate the system that I have.

“It’s so comforting, surely, for patients to know that a provider knows at least something about their identity and specific aspects of health. That applies to any identity.”

Her annual PDx lectures have helped to engage future health practitioners with practical information about treating those who express and embrace LGBTQIA+ identities. Moreover, she works to increase visibility for LGBTQIA+ health practitioners by recruiting future physicians and scientists to Vanderbilt.

She maintains visibility is important for both patients and future providers, commending her program for working to be more welcoming for all students.

“It’s important for our students to feel safe to be out so we can be liaisons for the next generation looking for visibility in medical schools,” McNew said. “The MSTP leadership team is so incredible at picking students who bring what they want to see in academic medicine, then give the students the resources they need to create that space.

“It’s nice to see efforts starting at the ground level and working throughout careers.”

McNew hopes the School of Medicine will continue to integrate LGBTQIA+ Health education into curricula across its 10 professional degree programs. As an MSTP student, she has been at Vanderbilt since 2015, witnessing change in the student population over time. She remains hopeful for continuation of the work she and others have started to set a foundation for an increasingly welcoming environment.

Coming up on her seventh year giving the PDx lecture, she stands ready to pass the opportunity to the next generation, in large part thanks to her efforts and faculty support in recruitment.

“My college ‘Great-Great-Great Grand Little’ will be [giving the lecture] with me, and he will be taking it over. It will be great to have him there,” she said. “To have a space where there’s a lot of us working for change, it’s meaningful and powerful for people.”

She remains proud to know future applicants will see older students like them in Nashville and determined to create that space for patients who do not have the agency to navigate the health care system as trained physicians do.

She credits MSTP faculty with giving her and others space to generate initiatives through their training and professional networks.

“It’s not practical for advocacy to be our entire careers. We are being trained to be physicians-scientists, first and foremost. But advocacy can certainly be a part of our careers and how we accomplish our physician and scientist role responsibilities,” McNew said. “I think that MSTP is so good at finding ways for students to incorporate our advocacy into the training that we’re already doing. I think that’s not common at many institutions. MSTP has really seen the opportunity to fill the gaps in academic medicine to try to solve some of these problems that have existed for decades.”

McNew hopes the Vanderbilt community continues to think about all the ways individuals can be diverse. For instance, her wife worked to create a stronger support system for first-generation medical students historically restricted from entry into the field based on socioeconomic status and other factors. She notes for patients, care might mean much more coming from providers who can relate to them on the most essential levels.

She sees Vanderbilt as a place where inclusive medical practice can grow in all facets, championing her program faculty and the work of her peers.

“Vanderbilt has a lot of faculty members who are good at identifying when students raise concerns that need to be addressed, then giving students the freedom to do what they need to do to address that concern,” she said. “It’s hard in practice, but at Vanderbilt, people are very good at giving students the space to pursue what they need to. To create a space for themselves and their communities. I really love Vanderbilt and have been very happy here.”

George C. Hill, PhD, Vanderbilt University Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology, gave the 20th annual Levi Watkins, Jr. MD Lecture on Oct. 5, 2021. In focusing on the courage of Watkins and Dr. Vivien Thomas as trailblazers in minority medicine, Hill reminded the audience that health equity may be accomplished through collective contributions, and Vanderbilt University School of Medicine remains proud to recognize its students for their individual efforts.