Student volunteers learn, lead during winter weather

As a winter weather crisis crept across Middle Tennessee, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine students responded to needs at Vanderbilt University Medical Center

by Lexie Little

The news coverage continued. Snow blanketed the mid-state as temperatures plummeted. Cars sat stranded on ramps and side roads as ice crackled across asphalt. Sidewalks likewise proved treacherous. Restaurants and schools closed early. But the doors at Vanderbilt University Medical Center remained open.

Standing in the Command Center watching each broadcast update and listening to weather radios, Dr. John Morris, associate chief of staff for the Vanderbilt Health System, readied plans for the hospital’s response, which for the first time, included a team of medical student volunteers like M4 Roman Gusdorf.

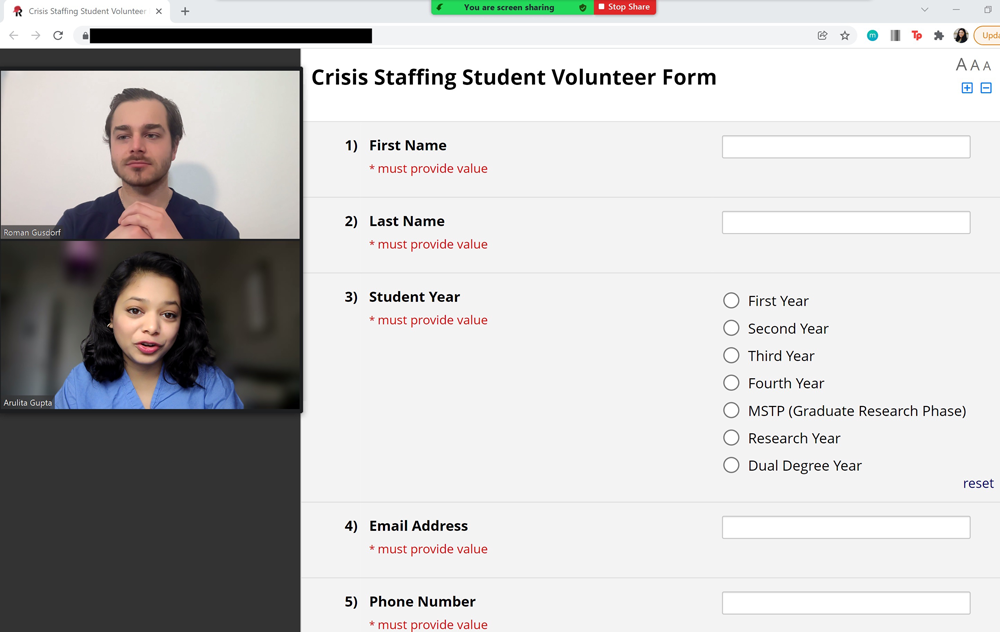

Gusdorf, along with MD-MBA student Arulita Gupta, did not realize how quickly they would need to work to implement an operations strategy idea that manifested in December 2021. With the help of Morris and Associate Dean for Medical Student Affairs Amy Fleming, they had devised a medical student volunteer program for inclement weather and/or mass casualty events.

“I was excited to develop this program after Dean Fleming told me that during a bad snowstorm, there might only be a 10% decrease in patients but around a 30% decrease in staff,” Gusdorf said. “That seemed clearly the case when we arrived to volunteer. There were around 50 nurses, care partners, and EVS staff unable to get to the hospital out of around 350 scheduled to work that evening. So, we stepped in to help out with patient care.”

They quickly learned one of many lessons that day: expect the unexpected.

Responding to needs

As seven inches of snow surprised Nashvillians on Jan. 6 and 7, the opportunity to implement a newly-developed student crisis staffing program seemed just as unexpected. But the whole endeavor to that point had been a pleasant surprise for Gusdorf and Gupta, with nearly 50 students volunteering for future events in just minutes after the program’s creation—an encouraging nascence.

“We essentially sent out an email just garnering interest in the program, and we were shocked at how many people responded,” Gupta said. “We weren’t sure if students would be interested in behind-the-scenes jobs like patient transport, delivering food trays, etc. We even considered if there should be a spokesperson like Dean Fleming as the first point of contact to talk about this program and get more interest that way. The initial reaction we got from students was great. Twenty-five students signed up within the first hour of sending out that email. It was incredible and overwhelming.”

Of 47 students who registered to participate, 12 future physicians safely ventured to the adult hospital alongside a 13th student volunteer who made herself available in the moment.

Becoming part of the team

The team convened with VUMC leaders in front of the adult hospital chapel to learn their assignments based on shifts. Students free from 6 p.m. to midnight worked non-clinical shifts while those available for 12-hour shifts worked clinical rotations on the floors. Though she had finished a pediatrics rotation at the hospital earlier in the day, second-year student Samantha Singal decided she should volunteer, especially because she lived within walking distance and purchased new boots (perfect to trudge through the snow) shortly before weather hit. When the nurses on her team learned she had volunteered for a 12-hour shift, one nurse cried.

“When the nurse leader brought me to the floor, he introduced me to the charge nurse who asked me how long I would be there,” Singal said. “I said I would be there until 6 a.m., and she almost cried. Seeing how stressed everyone was, was tough. Everybody thanked us, the medical students, for relatively small tasks. It felt important that we be there…It didn’t feel like something that deserved that much thanks.”

Singal made her rounds, waking up patients every four hours to take vitals or clean bedside commodes. Humbled, she realized quickly how hard care partners work to mitigate disturbances to patients and implement holistic care, including emotional responses.

A patient receiving an infusion turned to Singal and gruffly asked, “How much longer will this take?”

Looking at the pump, she realized she didn’t know how to read it. As a second-year student, she learns on the job every day while navigating clerkships and various rotations. She did, however, know how to alleviate the situation.

“When I entered, he was fairly grumpy,” Singal said. “I joked with him, saying, ‘Yeah, they just let anybody into med school now,’ to lighten the mood. When I left, he was in a good mood.”

Reflecting on vital roles

Elsewhere in the hospital, Medical Scientist Training Program student Daniel Sack stepped in as a care partner for a small set of patients. Now in the graduate studies portion of the Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP), Sack encountered a side of medicine he’d yet to experience in practice.

MSTP students complete two years of the MD before turning attention to PhD studies and research. Following their PhDs, they return to the MD program. As a result, they spend more time at Vanderbilt than traditional MD students. Some of Sack’s former classmates now work as residents across the country, combatting issues he encountered during the crisis response.

“I know from talking to former classmates who are residents now how tired everyone is, having been in a pandemic for two years,” Sack said. “But it was very interesting as someone who has not been in the hospital as much with patients. In the unit where I worked, half of the nurses had come from other units to fill in. They didn’t really know the protocols specific to that unit. The other nurses had all been out the week before following COVID-19 guidelines. It was an up-close and personal experience, facing how society has continued to struggle in the face of this pandemic, not to mention the snow and ice.”

During that night shift, one in six scheduled nurses remained unable to get to the hospital. Sack and his peers experienced first-hand the necessity of their roles at a time when health systems already face critical shortages. Vitals and medication plans that nursing and care teams monitor overnight affect how physicians proceed with care plans the next day, and Sack noted the necessity of such interventions.

“This experience reiterated in a tangible way how important decisions about discontinuing or creating new orders remain to good patient care,” he said. “We always recognized these tasks are essential, and we were happy to contribute, but I don’t think we fully appreciated how difficult they could be (having not done them) and the extent to which physicians could make these roles more difficult by, for example, not discontinuing redundant orders. That appreciation is something we hope to carry forward as future physicians.”

The holistic picture of patient care stood out as an important reminder for each student. Gusdorf, working a clinical shift on the transplant floor, checked vitals, helped patients to the restroom, transported patients to the CT machine, and responded to pages from patients in pain.

Working with a nurse to administer medication to a patient, he felt a buzz in his pocket. He had received and logged into a nurse’s work cell phone to respond to assigned patients during the shift. As the patient buzzed him from another room, Gusdorf paused for a split second, realizing in a new way just how many distractions nurses and care partners encounter in their workflow.

“It was cool to see a different side of medicine from what my exposure has been from the perspective of a future doctor, where we put in orders that somehow magically get done,” Gusdorf said. “It was interesting being on the other side of things to watch medication administration, see vitals and weights taken, and find out how difficult it can be to get patients to the restroom. I learned to be appreciative of processes like getting medications to patients and how much work nurses and care partners do. They have to handle so many things at once.

“Even something simple like getting a CT scan can be a challenge. We as future physicians could often wonder why a patient hasn’t gone to CT yet, but it can be really difficult to get that patient up and transported in a safe manner, or they may be in the restroom or something else gets in the way of the process, completely out of the care team’s control. I will better appreciate the roles that these teams fulfill and understand some of the delays that physicians might not often see.”

Carrying lessons forward

Leaving the hospital the next morning, those appreciations resonated in a reciprocal fashion. Singal had entered the night with little hope she and her classmates would be able to help in a substantive way, given all the tasks that needed attention. She felt relieved to hear from nurses that they were grateful the students had volunteered, hoping contributions had eased their jobs.

Following the shifts, feedback surveys rolled in to Gusdorf and Gupta.

“I thought it was so exciting, and I was grateful the support we got and some of the surveys we received,” Gupta said. “I think one of the most insightful things we learned from the program was not only did people feel like they gleaned a lot from that experience, but we also reflected on how vital other positions in health care remain in the larger process of patient care. Like the individuals who sanitize rooms – that’s a really hard job.

“We got really excellent feedback from students sort of lifting that veil and looking at the other side to see what it’s like…We got feedback saying that there were literally tears in the nurses’ eyes when the students arrived. That moved me because extending just that little bit of empathy, grace, and humility goes a long way…”

More than they could expect.