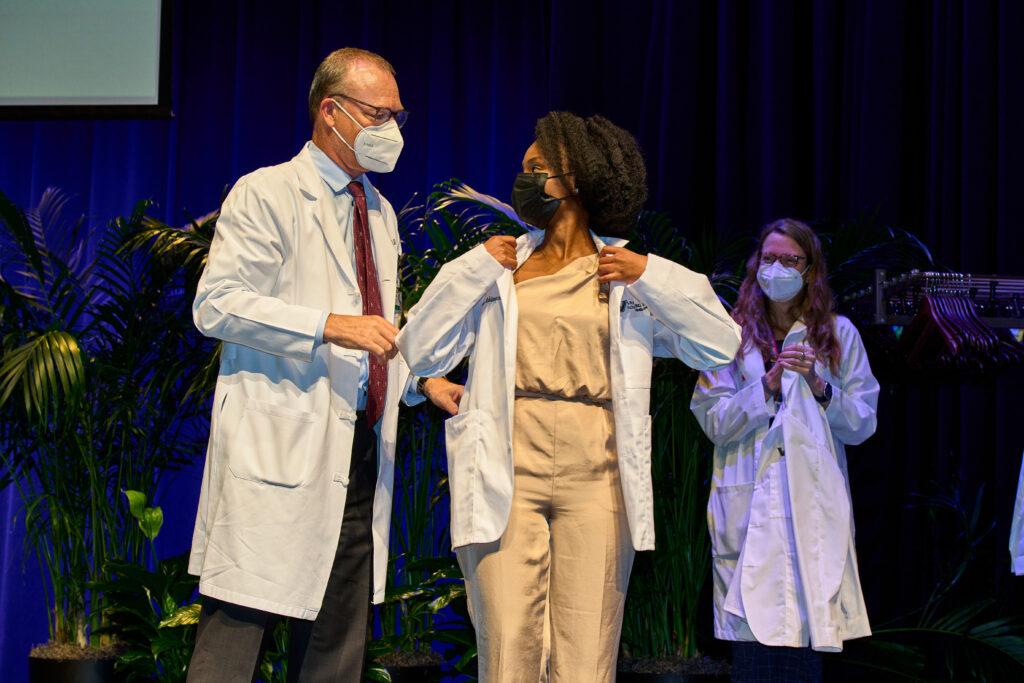

Sylvie Muhimpundu (MPH ’19, MD ’26) applies a degree of experience

Rwanda native Sylvie Muhimpundu wanted to be a physician well before she ever came to the United States. Now, she’s working on her second degree from Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

By: Lexie Little

Shuffling past bustling cars along 21st Avenue in Nashville, Sylvie Muhimpundu reviewed they day’s tasks ahead in her mind as she made her way to work at Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, where she served as a senior research specialist. Traffic on the road beside her slowed to a stop in the morning Starbucks coffee rush line. Muhimpundu, too, stopped in her tracks.

Her phone rang. She answered and heard the words she’d longed to hear: “Congratulations! You have been admitted to the first-year MD class entering the School of Medicine at Vanderbilt University for Fall 2022.”

“I remember when I found out, I was walking to work, and I walked along 21st crying, and I didn’t know what to do with myself. I didn’t know how to act in that moment. It was a good moment. I hoped nobody was looking at me,” she said, laughing. “I feel like with something you have wanted for that long, you come to a point that you start saying, ‘That’s what I want, but that’s not necessarily where I’m supposed to go. Maybe I could try other things.’ At that moment, that was what I wanted and what God wanted me to do. I realized, ‘Oh, this is truly where I’m going. This is going to be my life.’”

As an adolescent in Rwanda, she witnessed first-hand the tolls of cancer on family, friends, and community members. She gained an interest in medicine and oncology, inspired by the need she saw at home. Muhimpundu traveled to the United States, where she studied biochemistry at Oklahoma Christian University.

Navigating a new educational system, she realized she also wanted more exposure to the health care systems in which she would put that training to use. She applied to Vanderbilt’s Master of Public Health program to learn more about systems of care, social determinants of health, and global health.

“Even as an undergrad, I wanted to go to medical school,” she said. “Through networking, I began volunteering and shadowing, and I realized I needed a deeper understanding of public health and how the system works here in the U.S. and globally. I thought, ‘Why don’t I just apply for a master’s degree and learn about the disparities that led to patients that came to the free clinic, usually underserved populations. When I started the MPH program, I was shocked by how much I learned and how much would be important to me for my medical career. Other people usually start in medicine, then go on to do research later. It was backwards for me. I researched in the public health space, and that informs what kind of physician I want to be.

“The main thing that I did in the public health program that will help me in the next phase of my career is that exposure to research. I feel like during my time there, I fell in love with research. It made me realize that you can see patients and treat them, but you can also have a deeper understanding of diagnoses and diseases through research, specifically for underserved populations. It opened a door in my mind to ask not only what is happening, but why is it happening? When we are studying diseases in class, I find myself thinking, ‘Who would be more vulnerable to this disease and why is that happening?’ There are social determinants of health beyond whatever genetic makeup and hereditary influences. That [public health experience] was important to me and who I want to become as a physician. I feel like I will carry that same mindset into clinic: ‘Why am I seeing this patient in this context? Why is this [medical issue] happening?’”

As an MPH candidate on the Global Health Track, Muhimpundu studied racial differences in liver cancer risk and completed her practicum work investigating a cancer cluster in Grainger County, Tennessee, through the Tennessee Department of Health. She earned recognition as a David Satcher Public Health Scholar for the Class of 2019, receiving a two-year scholarship. She researched in the Pediatric Infectious Diseases department with Dr. Halasa Natasha and in the epidemiology department with Staci Sudenga, PhD. She worked on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Emerging Infections Program (EIP) vaccine surveillance project at Vanderbilt examining both the flu and HPV vaccines.

She credits mentorship with reasons for her success. She said mentors in the public health program showed her how to effectively conduct and apply research and practices in addition to encouraging and pushing her to carry on with her thesis project. She knew if she came to Vanderbilt, she would have such support. And she knew if she stayed here for her MD, that support would continue.

Sudenga, an Assistant Professor of Medicine in the Division of Epidemiology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, served as Muhimpundu’s thesis mentor and has known her for more than three years. From the start, Sudenga had no doubts Muhimpundu would be a successful physician scientist.

After discussing several projects with Sudenga, Muhimpundu chose to focus on “Racial Differences in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Incidence and Risk Factors Among a Low Socioeconomic Population.” Sudenga said data for the project came from the Southern Community Cohort Study (SCCS), which is a prospective study designed to assess the determinants of racial and socioeconomic differences in cancer and other diseases among over 80,000 research participants.

“This project was a huge undertaking for Sylvie since we both had never worked with this data before,” Sudenga said. “Sylvie took charge of reviewing the data dictionaries, drafting the necessary feasibility and concept proposal forms for acquiring the data, and working with the SCCS staff to build the dataset. She then was responsible for data analysis, interpreting the results and drafting the manuscript. While this was a collaborative effort, Sylvie took the lead in all aspects of the project with very little oversight from me. Her tireless work ethic and outstanding performance led to a first author publication for her.

“From conversations with Sylvie, she has always known that medicine is her passion and career choice, but this research experience has broadened her career ambitions to include research. Our project focused on liver cancer with the hopes of identifying risk factors by race that could lead to prevention. Throughout our project, Sylvie could easily identify the value of using medical research to drive clinical practice. [She] quickly distinguished herself as an MPH student that takes heed to clear direction and has the initiative to produce results with very little oversight…She exceeded expectations and demonstrated an impressive knowledge and comprehension of our project goals and processes.”

Muhimpundu’s time as an MPH student revealed the intersections between public health, medical research, and clinical practice she hopes to apply to her future work.

“Research, public health, and clinical practice go hand in hand,” she said. “When I was doing research on liver cancer, looking at risk factors of liver cancer and how they affect different races, [the study] had a component of public health, because I was investigating different communities. I had the research component rooted in epidemiology, and all of that can be applied in clinic. When I am a physician, I will have that clinical perspective when I see my patients, knowing I need to account for known risk factors and who might be more affected by them. That will inform how I treat my patients and how I work with other practitioners to come up with broader public health solutions for care. I want to bridge the gap that exists between public health practitioners and physicians.”

After completing her MPH, Muhimpundu joined Vanderbilt University as an employee in the School of Nursing Center for Research Development and Scholarship as a senior research specialist. When the COVID-19 global pandemic hit Middle Tennessee, she and other volunteers mobilized to help combat the virus. Putting her public health background to work, she joined the mobile vaccine clinic effort to serve underserved and underrepresented populations.

“We went to communities like local immigrant communities and underserved communities to give them access to the vaccination,” she said. “I think some of the things I learned in the public health program was really why I thought about that – how can I help, how can I reach out to the communities? I was reminded that medicine alone is not enough. There has to be a way to connect health care to the communities it serves, and public health becomes that bridge. There is a need to meet people in their communities, in particular for initiatives like vaccination that require trust from the community. Sometimes, you have to go into these communities and work with them to improve their health. For example, in most communities we went to, people were more willing to take vaccines if leaders from their communities explained why the vaccine is important.”

With that experience in mind, Muhimpundu wants to eventually expand her work globally, specifically fulfilling a dream of building cancer prevention and treatment programs.

Just as she did in Nashville, Muhimpundu realizes work begins with reaching out to the communities and leaders like those in her home country.

“I will need to tap into the networks of stakeholders who will most likely benefit from my work there,” she said. “Especially going abroad, back home to Rwanda, as someone trained in the U.S., I don’t as fully understand the local needs and priorities of communities there. My goal now is to figure out how I can get involved, and most importantly how to be the most useful in Rwanda.

“Working in global health requires cultural humility and understanding global communities it serves. Sometimes, the lack of cultural humility observed in the largely western-based global health domination creates biases and unintentional harm to communities they serve. So, it is really important for me to understand local priorities. I think solutions have to come from the communities, then collaborate with physicians to figure out how best to help them.”

Now, Muhimpundu looks to apply her experience to studies as an MD student at Vanderbilt. She decided to stay at VUSM because of its emphases on mentorship, research, and community. MD students follow a four-year research pathway as part of the innovative Curriculum 2.0 (different from the Medical Scientist Training Program, or MSTP, in which students earn both an MD and PhD). She carries her love of research into the program, looking forward to applying her public health and research knowledge in clinical settings.

She and her classmates have already gained a taste for life in clinic through first-year curriculum elements like physical diagnosis and the fundamentals of health care delivery.

“We have great clinical exposure in the program,” she said. “I’m already seeing clinical spaces within the first block. We’re already in the hospital for some of our physical diagnosis and continuity clinic courses. It’s really amazing.”

Muhimpundu also relishes in the opportunity to conduct more research during her time as an MD student. She chose to remain at Vanderbilt in part because of the research elements built into the unique curriculum. Students explore and plan for research projects of their own interests within medicine during the first two years of study before completing a three- to six-month research immersion. Research immersion allows students to work full-time on a research project for a publication-ready final paper.

Through each phase, she plans to bring prior experiences to inform her path. Her research and public health background inform the ways she approaches cases in class sessions, the way she thinks about future desires to combat non-communicable diseases in developing countries as a physician, and the ways she seeks to balance her studies with her life in Nashville – both through service and hobbies outside of campus.

She hopes students who followed a less traditional path to medical school will equally embrace their experiences as a positive.

“I think the advice I would give to any student not following a more traditional trajectory is that your experience really can be used in medicine,” she said. “Medicine is a broad career, and past experiences like research, and volunteer work, and even life before any schooling can be valuable. Looking at the trajectory of me getting here, me being in Rwanda, I started to have an interest in cancer because family members and friends were dying of cancer. At that time, we didn’t have the cancer services that exist in some places now. They didn’t have treatment resources and care for that. Now, they do, and they’re doing amazing, and I’m so impressed every time I go home. But at the time, that informed how I went to undergrad and studied biochemistry, then went on to study public health, then came here for medical school.

“Building on those experiences each time and looking at life as a full circle, it’s important to make sure you don’t lose that experience from each period of your life. For some people, they do something that has nothing to do with medicine before coming to medical school. But there are skills you get from those experiences like communication or something else that you can use…Use that for your own benefit if nothing else.”

Muhimpundu also advocates for keeping an open mind while honoring your passions. Her experiences in Rwanda sparked an interest in oncology that continues to this day. But she keeps an open mind, especially while rotating in clinical spaces during her M1 year.

While she still holds a desire to pursue oncology as a specialty area, she doesn’t stop herself from learning in other areas. She doesn’t want to miss any opportunity for growth; after all, it might lead to another stop on a successful career path.

“Right now, I’m doing my clinical visits at the orthopaedics clinic, and it’s really interesting,” she said. “There are things I’ve never had exposure to, and it’s so interesting to see some of these procedures and issues. Maybe I’ll switch? I don’t know. I’m staying open minded so that I don’t miss any opportunities.”

With several more years of medical school ahead, she has time to find the right path for her. But for now, she’ll apply all she has learned and continues to learn in the neighborhood around 21st Avenue.