2020 MSTP grad Kevin Graepel shares his four-year experience researching coronaviruses

by Emma Mattson

Kevin Graepel describes his early experience of the COVID-19 pandemic as a “rapidly escalating sense of dread.”

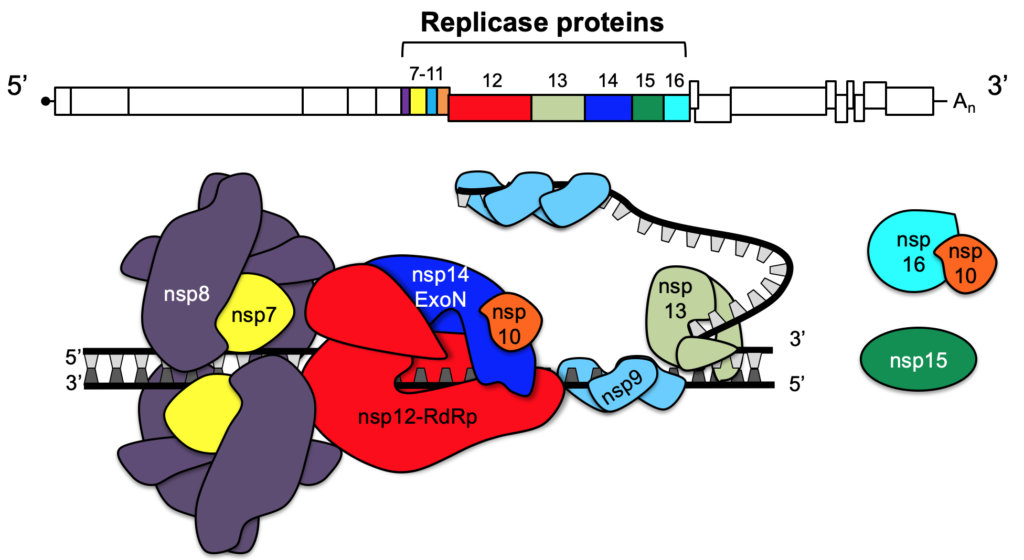

Graepel, who graduated from VUSM in early May with an M.D./Ph.D. could be considered something of a coronavirus expert. He spent his Ph.D. years researching in Dr. Mark Denison’s lab, studying how a specific coronavirus protein called exoribonuclease (ExoN) functions during viral replication— a key process for developing antiviral drugs.

“I consider his work some of the most interesting and important work we’ve ever done in our lab because it’s so basic to our understanding and moving forward,” Denison said. “When I present that work, virologists are very excited about [Graepel’s] work because it really reveals very important biological principles of the virus.”

The Denison lab has studied coronaviruses for nearly three decades. When Denison started his lab, the coronaviruses known to infect humans primarily caused the common cold. Since 2003, however, several new coronaviruses have emerged.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) are two well-known examples of coronaviruses that emerged from animals and caused human disease. For years, the Denison lab has worked under the assumption that at some point another coronavirus would follow suit; they just didn’t know when the new one would arrive.

“I first heard about the new virus in December,” Graepel said. “I was concerned but not surprised. We knew it could cause severe illness, but at the time, we didn’t know if it was transmitting between humans. We didn’t really expect that it was going to become a pandemic.”

Instead, researchers were comparing the current coronavirus to SARS, which had shaken the global scene back in 2002. Although serious, SARS produced relatively few fatalities. In the U.S., for example, there were only 73 known cases and zero deaths.

“The experience with SARS was that it really didn’t transmit between asymptomatic people. If you had a SARS infection, you didn’t infect anyone else until you were already in the ICU, for the most part,” Graepel said. “By the time you were there, it was a lot easier to contain it because you had healthcare workers with PPE and disinfectants.”

COVID-19 was different.

By early January, it had become clear that not only could the new coronavirus spread between humans, it could also be transmitted by asymptomatic people, who might not even know they were infected.

“That’s when it got a lot scarier,” Graepel said. “I started talking to my family about the possibility of a pandemic in early January.”

When COVID-19 broke out, Graepel had already completed his Ph.D. research and was finishing up his final year of med school. But because of his experience in the Denison lab, Graepel had a body of relevant knowledge to share with the world.

The immediate option was to return to work in the Denison lab. Denison reached out to VUSM leadership with an urgent request that an exception be made to the off-campus work policy so that Graepel could return to work in late March.

“The second I heard about it, I wanted to try to get him back in the lab,” Denison said.

Unfortunately, multiple factors—including specific safety requirements in the lab, Graepel said—did not allow Graepel to return to work in the lab. This didn’t mean he couldn’t help in other ways, however.

“I had a certain set of skills that really could be beneficial,” Graepel said, “so I was trying to think about what I could do with my knowledge base that might be valuable.”

“[Graepel] is a great example of why we need to continue to train physician scientists—people who will be excellent physicians but also continue to ask key fundamental biological questions,” Denison said.

Graepel began working with the Vanderbilt Health Policy Group on advisory documents for state and local Nashville COVID-19 policy. He provided guidance for other members of the Denison lab. And he reached out to Kathryn Edwards, M.D., pediatrics chair and one of the top names in vaccine research. Together they wrote a perspective piece for The Journal of Infectious Diseases discussing the particular challenges of vaccine development in the midst of a pandemic.

Their article, “Balancing Expediency and Scientific Rigor in SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Development,” was published May 4 by The Journal of Infectious Diseases.

Overall, Graepel said, the COVID-19 pandemic underscores the need for extensive funding for scientific research, even without an immediately pressing reason.

“We need to be funding things that we don’t necessarily know what we’re going to do with or don’t have an immediate need for,” Graepel said. “If the Denison lab hadn’t gotten money from the NIH to study coronaviruses when they weren’t an immediate threat, we’d be years behind in the whole process.”

Instead, enabled by federal funding and academic and industrial collaborations, the Denison lab began testing antiviral compounds against coronaviruses several years ago, Graepel reports. One of these compounds, remdesivir, was recently approved by the FDA for emergency use in COVID-19 patients. The antiviral works by blocking viral replication, the very process Graepel spent his Ph.D. years studying.

According to Denison, the lab has been working around the clock to test different antiviral drugs, including remdesivir, against the new coronavirus. Other members of the lab are continuing the research Graepel began, looking for ways to weaken the coronavirus.

In the meantime, Graepel himself enters a new arena of the fight against COVID-19. After graduating from VUSM earlier this May, he will begin his pediatrics residency at St. Louis Children’s Hospital this fall.

“[Graepel] is a great example of why we need to continue to train physician scientists—people who will be excellent physicians but also continue to ask key fundamental biological questions,” Denison said.

Learn more about our Medical Scientist Training Program.