From printmaking to pediatric practice, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine student Steven Scaglione looks to connect with people

By: Lexie Little

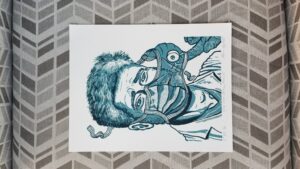

Steven Scaglione dusts shavings off his most recent wood carving. Working groove after groove, day after day, an image assembles that he readies to ink like a giant stamp. As an undergraduate student at the University of Alabama, Scaglione had taken Introduction to Printmaking, a course outside of his microbiology major requirements. Now a fourth-year medical student, he still works to perfect his craft, using controlled pressure by his own hands to transfer images to paper.

The pressures, the lines, look ever so slightly different on each transfer, making each print unique: one-of-a-kind, not unlike the patients with singular circumstances he encounters as a future physician. Scaglione recently finished interviews for pediatrics residency. But he didn’t always know he wanted to be a doctor.

Not until medical school, at least.

Making first impressions

Walking into Dr. Reid Thompson’s Village at Vanderbilt Place clinic, Scaglione squeezed his hands as he looked around. His palms felt sweaty as the clinic staff showed him to the work room. He waited anxiously as Thompson finished up with a patient. Suddenly, a man in a longer white coat perked up as he turned the corner toward the workroom.

“Are you Steven?” Thompson asked.

“Yes! Hi, Dr. Thompson,” Scaglione said, working up his confidence and reaching out his hand.

Then, the respected physician did something Scaglione hadn’t expected.

“He took my hand in like a ‘bro handshake’ and gave me a half hug,” Scaglione said. “He said, ‘It’s so good to have you in the clinic.’ He just really welcomed me…I was expecting something more intense than the warmness he showed me in that clinic.”

As a first-year medical student assigned to Thompson for the Foundations of Health Care Delivery continuity clinic, Scaglione entered intimidated by the Chair of the Department of Neurological Surgery’s reputation. He watched Thompson’s TEDx talk. He scrolled through publications. And he, the only member of his family to pursue a career in medicine, had little knowledge of the human brain’s pathology. He just knew his was about to explode.

Prior to entering medical school, Scaglione thought he might pursue a PhD in a scientific field, like his twin brother. But a journalism minor in college exposed him to conversations with people and human connections.

“Around my junior year at Alabama, I realized I wanted a lot of personal human interaction and connection because I really like that,” he said. “In thinking about combining those interests, medicine popped into my mind…I’ve interviewed people before and just really liked the magic that a simple email could get you. ‘I wonder if this person would talk to me about this thing that they’re interested in?’ You send it, they get back to you, and suddenly you’re sitting there talking with someone and diving into a story they’re able to tell you and share their expertise. It was a little bit of that interaction that made me realize I liked working with people and their stories. I could do that with science, too. I would just need to be a little more intentional about it.”

Thompson would show him how to do just that.

Turning images into action

After examining an MRI together in the workroom, Thompson realized the patient waiting to see them had a benign tumor that would not require surgery. Scaglione looked at the surgeon, somewhat stunned to learn some brain tumors require little more than monitoring. But as an M1 whose Brain and Behavior course block wouldn’t come until the end of the year, he had no reason to be anything else: an inquisitive learner focused more on patient care than on diagnoses.

“I wasn’t expected to know the pathology I would be seeing, and Dr. Thompson made it very clear that he wanted me to learn from that experience how to treat patients, not how to treat disease,” Scaglione said. “Not how to treat surgically, but how to treat patients as humans. He wanted me to learn how to work with other people in the clinic. My training there wouldn’t be knowledge-based. That was new to me because a lot of what is rewarded in medicine is medical knowledge. I think you have to have the medical knowledge, but the best doctors go above and beyond in investigating and relating to the people we’re treating.”

The academic medical duo walked into the room where the patient sat with his wife.

“Well, sir, you have a benign tumor that will not require surgery,” Thompson said, explaining the exact type and its consequences. “We will continue to monitor its size and position in the meantime. What questions do you have for me?”

The patient looked at Thompson blankly and said, “You mean, I’m not going to die?”

Thompson reassured the patient he would not die from the tumor and explained the medical condition and course of action further, taking the time to sit with him in a teachable moment – both for the patient and for Scaglione.

“Dr. T understood the gravity of those conversations. Maybe a different surgeon that wasn’t as thoughtful would realize it’s not a surgical problem, tell the patient that, and simply send them on their way. But Dr. T understood while that’s in the background, this guy thought he was going to die for four months, and we needed to acknowledge that and set the record straight, answering questions. His patients love him for that.”

That empathy and attention resonated with Scaglione. Printmaking takes patience to carve out designs and images. The art requires an attention to detail. But it also requires a fraction of the human spirit, an acknowledgement of feelings that prompt an artist to create and share. Likewise, medical practice requires patience to answer patient questions; detail to accurately explain a diagnosis and seek the holistic care plan; and an acknowledgement of patients’ stories and feelings that make them receptive to care, placing trust in the physician.

Thompson noticed that attention in his student.

“Steven has all the qualities one would want in their doctor: he is brilliant but humble; sensitive, kind and deeply compassionate,” Thompson said. “He is a gifted artist and sees the art in the practice of medicine. It has been so wonderful to see him blossom in medical school at Vanderbilt. I can’t wait to see what the future holds for him!”

Etching reminders of humanity

The following year, Scaglione made his way to Vanderbilt University Medical Center for clerkship rotations at the hospital. He applied what he had learned with Thompson to patient care there: acting as a go-between for patients and physicians in the clinical setting, learning as he presented cases both for patient understanding and for his supervising residents, fellows, and attendings.

But his patience and empathy would be tested another way. When the COVID-19 pandemic forced virtual classes in Spring 2020, Scaglione looked for a way to stay involved in health care. Volunteering with Metro Nashville Public Health Department and Vanderbilt Occupational Health, he acted as a contact tracer for those who recently contracted the virus.

He picked up the phone to dial the next number on the list. The sheet in his hand codified people facing a serious health crisis in an amalgamation of letters and numbers.

“The fact that the pandemic and social interaction are tied to each other is a hard thing. We’re social individuals, we enjoy hanging out with our friends, we’re used to seeing people. Especially for someone like me who’s generally a curious person, I like to get to know people and dive deep into their lives,” Scaglione said. “When you have just a name and a phone number, you have no idea who that person is going to be – what their job is, what their values are, how they got COVID. You just know that they tested positive. You get the story, and you have to give them some guidance for what to do after that. While that phone was ringing, it was interesting to think about who would pick up and how they might respond to me calling them from a health department and saying they have to quarantine.”

A student picked up the phone, becoming defensive and scared as he explained he had traveled to Florida for spring break at a time when travel remained restricted. Scaglione thought about patients and the fear that sets in with diagnoses they don’t understand. Like with the patient at Thompson’s clinic, Scaglione needed to address those fears while trying to obtain business and contact names he would need to notify.

Moving on to the subsequent names and numbers, Scaglione tried to picture who the person might be and find a way to relate on a human level, especially as he listened to story after story of risky pandemic behavior.

“I feel like that experience taught me a lot so that when I am a doctor, I will be prepared to see people who are sick all the time. That’s my job, whether those people had more control over how they got sick or less control or no control,” he said. “It was a struggle and a reflection for me to think about how important it is for us to treat their sickness. It’s not our job to determine the moral failings of how they got sick. It’s a bad habit rooted in the nature of the work that we do.”

Each person remains fallible with their own imperfections, not unlike an individual art print where the block shifted or ink smudged. And Scaglione etched that thought into his mind to inform his future practice.

The final product

Now readying himself for a three-year residency in general pediatrics, he hopes to carve a path forward toward a subspecialty fellowship and eventual role as a mentor in academic medicine where he can serve patients and future students. He reflects on how intentionally his mentors like Thompson involved him in patient care and practice, hoping to one day do the same, sharing his skills and passion for people.

In the meantime, he will continue to share his art, starting with the Shade Tree Clinic Benefit Dinner silent auction.

“It’s a lot of work to make one image. You’re carving a lot of wood, and there’s a lot of shavings on the bedroom floor, but once you have the blocks done, you can make 20, 50 prints, and that reprinting is not much work,” Scaglione said. “I like that because I like giving little prints away to my friends at school and sending them in the mail. It was just a nice hobby that had a creative process, but if I wanted to give something to someone, I wouldn’t have to spend another four hours drawing it. I could just print another copy and send it away. People like them.”

And Scaglione likes people.