MIDP student Sai Rajagopalan teamed up with experts across the world to bridge a specific gap in maternal-fetal care during COVID-19

by Emma Mattson

Social distancing over the past four months has challenged medical students across the country to adapt. Some have developed innovative solutions for digital learning, clinical work, and student leadership in the time of COVID-19. Some, like third-year MIDP student Sai S.V. Rajagopalan, have dedicated their energies to hacking.

Hacking the coronavirus, that is.

Sai spent the first weekend in May leading a team through one of MIT’s COVID-19 design challenges, a virtual hackathon entitled “Africa Takes on COVID-19.”

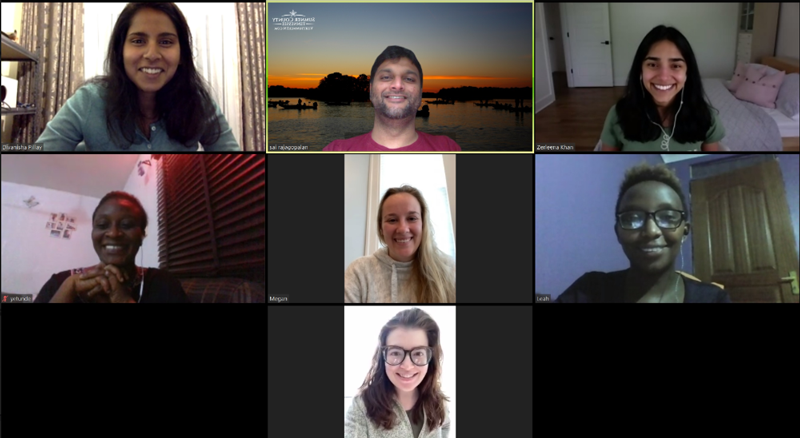

Sai’s team, composed of seven experts across various fields, was one of three winners chosen for its category: Sustaining Primary Care During COVID-19. Now the team turns its attention to implementing a prototype of their solution in South Africa.

More than 1500 people around the globe participated in the challenge, which took place over the span of 48 hours, from the afternoon of Friday, May 1 to the afternoon of Sunday, May 3.

From eight available design tracks, Sai immediately chose to focus on primary care. When he pitched a design question based on delivering care to patients by empowering traditional and non-traditional healthcare providers, an impromptu team quickly formed around him: Divanisha Patel, a PhD candidate in Artificial Intelligence at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa; Dr. Yetunde Ayo Oyalowo, public health physician at Community Health in Lagos, Nigeria; Zerleena Khan, an accountant in Nashville; Margaret Hannah, pediatrics resident at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore; Leah Kigondu, program manager at Afya Plan in Nairobi, Kenya; and Megan Lynch, healthcare consultant at Syneos Health in Boston.

The team aimed to address the pandemic’s recent disruption of prenatal primary care. Their goal? To connect pregnant women with adequate prenatal care, so as to identify women with preeclampsia, a vascular condition that requires careful medical management to prevent maternal-fetal mortality and morbidity

Sai says the barriers to pregnant women getting adequate healthcare in countries like South Africa are manifold, especially during COVID-19.

“One, there are ongoing curfews or lockdowns for COVID, where you can’t leave,” Sai said. “The second thing is the hospitals might be either closed or restricting the patients that they can see. And the third point is that, even if patients overcome the fear of venturing into a healthcare facility, transportation is difficult to find.”

After the team members mapped out these primary impediments, they spent the next 48 hours building a creative solution designed specifically for the country of South Africa. The result was a three-pronged solution they call Birthing Bridge.

First, Birthing Bridge sends messages encouraging pregnant women to come to clinics for medical checkups, since emerging data suggests a reduction in prenatal primary care visits, Sai said.

Second, Birthing Bridge recruits healthcare providers and women in the local community whom pregnant women will be more likely to trust. These community members will help disseminate information about prenatal care and mental health resources, as well as provide emotional support during a time of social distancing.

Finally, Birthing Bridge provides a platform that will securely connect soon-to-be-mothers with a primary care physician or a community health worker. Individuals can connect with any phone, smart or not, and if a woman reports symptoms of preeclampsia, then the physician on the other end of the line will help expedite and manage care accordingly.

At the end of the weekend, the team presented its solution virtually to the challenge participants, mentors, judges, and organizers and became one of three winners from their category. The award carried a modest cash prize, but, more importantly for Sai, it offered the chance to make the Birthing Bridge a reality.

Currently, the project is transitioning from an info-gathering phase into an implementation phase. In partnership with an existing healthcare tele-informatics company in South Africa, the team is establishing a Birthing Bridge pilot program. The resulting data will help them apply for grants to support future expansion, with the ultimate goal of establishing a model that can be replicated freely by any organization around the world.

Support from the Vanderbilt community has played a crucial role in this process, Sai said, expressing particular gratefulness for the support of MIDP adviser Brent Savoie, M.D., J.D. and the Vanderbilt Institute for Global Health.

“I would attribute a lot of the success to the program I’m in, MIDP,” Sai said. “We learn how to think about problems and solutions in a way that’s different than you would normally do in a research environment. It’s not research, because information is already there and you’re trying to turn it into a tangible result that directly benefits patients. More importantly, we get the opportunity to work with a forward thinking and innovative medical center like VUMC.”

In fact, Sai has been preparing for a challenge like this his entire life. As a child, he watched his mother, a primary care provider for the federal government in India. Her work sparked Sai’s interest in global health, but an affinity for math and physics (accompanied by what he describes as “crashing and burning” in biology class) attracted him to engineering rather than to a pre-med track.

“I am glad I started my education grounded in math, physics and engineering,” Sai said, “because one builds a strong foundation to digest abstract information from disparate disciplines and put them together to make real-world change.”

After completing his Ph.D. in mechanical engineering from The Ohio State University, Sai worked in the industry for more than seven years— an experience which prepared him well for problem-solving design challenges like this one.

“Taking ideas into a prototype and then trying to get buy-in from someone who was willing to implement—that was my daily job for many years,” Sai said.

But even after completing his engineering Ph.D., the thought of a medical career continued to haunt Sai.

“For some reason, I continued to volunteer in medicine. And then one fine day I was like, well, it doesn’t make any sense that all my fun stuff is in medicine,” Sai said. “So that’s how I decided to take the MCAT and see what happened.”

This fall Sai enters his fourth year of med school through the Medical Innovators Development Program at Vanderbilt, and the May 1-3 challenge is not the only one he’s participated in. In fact, he recently played a role in organizing MIT’s Beat the Pandemic II, another 48-hour virtual hackathon, which took place May 29-31.

As a physician scientist in-training, Sai aims to apply his dual expertise in mechanical engineering and medical fields to the global health problems facing the world. MIT challenges like these are only the beginning.

These kinds of challenges represent something Sai calls “the democratization of innovation.” It’s not who you know personally; it’s about the new ideas and passion you bring to make positive change happen around the world. And that’s exactly the kind of work he hopes to continue doing throughout med school, residency, and beyond.